A tool to analyze the greater forces driving your employee’s performance

In my previous post, I discussed the scenario where an employee’s behavior is poor, but it is plausible that the employee acted consistently and as one would expect him to behave, so it really isn’t clear that the behavior is poor. The example I used was the case of Jacob, who makes a tactical error of taking efforts to get around resistances and get in front of the VP to get her attention on a proposal. The VP turns then turns around and asks you to rein in Jacob, although this tactic has worked before for Jacob. What do you do?

Do you tell Jacob that he did a bad job, that he upset the VP, and to not confront the VP anymore? Do you ignore the request by the VP to “rein in Jacob?” In this post, I’d like to discuss a way to analyze the situation. In the next post, I’ll describe how to approach the conversation with Jacob.

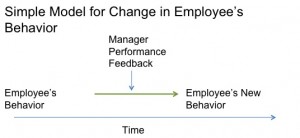

In most examples of performance or corrective feedback, it is assumed that the employee has been observed engaging in behaviors that are not meeting expectations, and the coaching and feedback provided will guide the employee to perform differently and to better results. The focus of the conversation is usually entirely on the employee’s behavior, and not the forces around the behavior that could be a major influence. This follows a typical and simple model for the impact of performance feedback:

In this model, the employee’s behavior is basically in a vacuum. The forces that went into the behavior are ignored, and the employee is in complete control of the situation, and the feedback from the manager course-corrects the error and the new behavior is now correct. There are many instances where this is the correct model to operate under, but there are perhaps more situations, such as the case with Jacob, where this model is too limited.

In this model, the employee’s behavior is basically in a vacuum. The forces that went into the behavior are ignored, and the employee is in complete control of the situation, and the feedback from the manager course-corrects the error and the new behavior is now correct. There are many instances where this is the correct model to operate under, but there are perhaps more situations, such as the case with Jacob, where this model is too limited.

What would happen if you tell Jacob not to ambush the VP in the future, as the VP has requested? Presumably, Jacob would stop ambushing the VP. Since other forces are not accounted for, the down side to this feedback is that Jacob no longer will get in front of the VP, the proposals will not be reviewed, his deliverables will be late, and the results will no longer be there. You will then have to have a different performance feedback conversation: “Jacob, you need to be more aggressive in getting your proposals in front of the VP. Perhaps you can catch her after a meeting?” At this point, Jacob will see the feedback provider as forgetful, unhelpful, and stupid.

So the manager needs to increase the sophistication in addressing the employee’s performance. There is still a desired change in how the employee performs, but just telling the employee to do it differently will not result in a new desirable behavior.

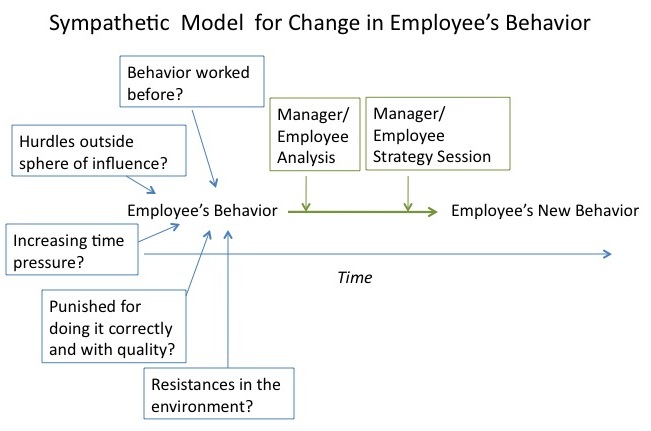

The new sophistication relies on a more sympathetic model of employee behavior that attempts to understand what went into the employee’s behavior:

In this model, when the manager learns that Jacob has done something wrong (i.e., ambushed the VP and the VP didn’t like it), the manager now has some basic questions to ask and analyze whether what Jacob did was wrong, or if the system is more the culprit. In our example:

Has the behavior worked before?

–Yes, Jacob has tried this before, and it worked to great success, even it if was risky

Are there hurdles outside the employee’s sphere of influence?

–Yes, the administrative assistant doesn’t respond to requests for time

Is there increasing time pressure?

–Yes, the proposal is time sensitive, requiring a bold and risky move

Is the employee punished for doing it correctly and with quality (or has quality not yet been defined)?

–Yes. Talking to VPs informally is considered an asset to the culture, and normally OK. Not this time. Also, going through the admin caused delays and worry.

Are there resistances in the environment?

–Yes. The VP is going through a tough budget review cycle, and is also booked up on a backlog of other issues, and is not thinking about new proposals now.

In Jacob’s case, 5 out of 5 questions were answered “Yes!” By asking yourself these questions, you can better put yourself in Jacob’s position, and it means that your feedback conversation will necessarily be different than just saying, “Don’t ambush the VP.”

By asking these questions, you will surface some key environmental and political factors that went into an employee’s performance. As a result, you will be better prepared for a conversation with your employee, and you will come across as more sympathetic to your employee’s situation. It’s better than just assuming you can correct the employee, and it gives an entry path for a conversation (so you just don’t avoid the situation).

Have you ever considered these factors when approaching a feedback conversation with your employee? What other “systemic” issues have you identified that could be affect an employee’s behavior?

In my next blog post, I’ll discuss more about how to have this complex, sympathetic feedback conversation with your employee.

The Manager by Design blog provides twice-weekly people management tips and discussion on the emerging field of Management Design. If you are looking for ideas on how to be a better manager of people and teams, subscribe to Manager by Design by Email or RSS.

Related Posts:

When an employee does something wrong, it’s not always about the person. It’s about the system, too.

Providing corrective feedback: Trend toward tendencies instead of absolutes

Behavior-based language primer: Steps and Examples of replacing using adverbs

How to use behavior-based language to lead to evaluation and feedback

Behavior-based language primer for managers: How to tell if you are using behavior-based language

Behavior-based language primer for managers: Avoid using value judgments

Behavior-based language primer for managers: Stop using generalizations