On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

Today I want to talk about a management team and how it relates to employees. Imagine the management team. They are in charge of the project of evaluating the performance of their collective employees. In some organizations, they are asked to “stack rank” all employees in an organization, or at least put them in general categories, such as low performer, average performer, high performer, or some variation like, “Needs improvement” at the bottom of the rank to “High Potential” at the top of the rank.

OK, now the management team needs to do the work of ranking the employees. The person facilitating this process is likely to be the manager of the team of managers, or the manager above that. So you have a bunch of managers in a room discussing a large batch of employees’ performance, making arguments about who is a good performer, who is an average performer and who is a low performer. Oftentimes there is a forced curve that requires some people into the “needs improvement” bucket. Oftentimes these discussions have promotion implications and bonus implications. In the examples of companies that have adopted the “fire the lowest 10%” philosophy, it also has firing implications.

Inevitably, the employees know that this kind of thing is happening between the managers. This is a common practice at many large organizations, and a tough one to get right. I’m not really sure it is possible to get right, and here’s why.

In a discussion like this, each manager is armed with some data about the employee. As discussed frequently in this blog, that data about how an employee performed is limited at best, and non-existent at worst.

There are cases where there are specific metrics that are directly comparable across employees, and a certain amount of fairness can be achieved by this measure. This typically occurs with employees at the lower level of an organization, and if you have several employees doing similar or repetitive work that produces comparable metrics. This is decreasingly the case, however, as even – or especially — entry-level positions require more quality-minded, customer-oriented, problem-solving type thinking to achieve high-pressure work goals. So even when there are directly comparable metrics, there are many intangibles that come into play.

So inevitably, it seems that current management design requires that managers get in a room and essentially argue who is the best employee, whether they deserve a raise, and, in many cases, argue that the other employees are less deserving.

Now, what’s tough is that these decisions are way out of the employee’s control – even if they have done amazing work through the year.

Here’s why:

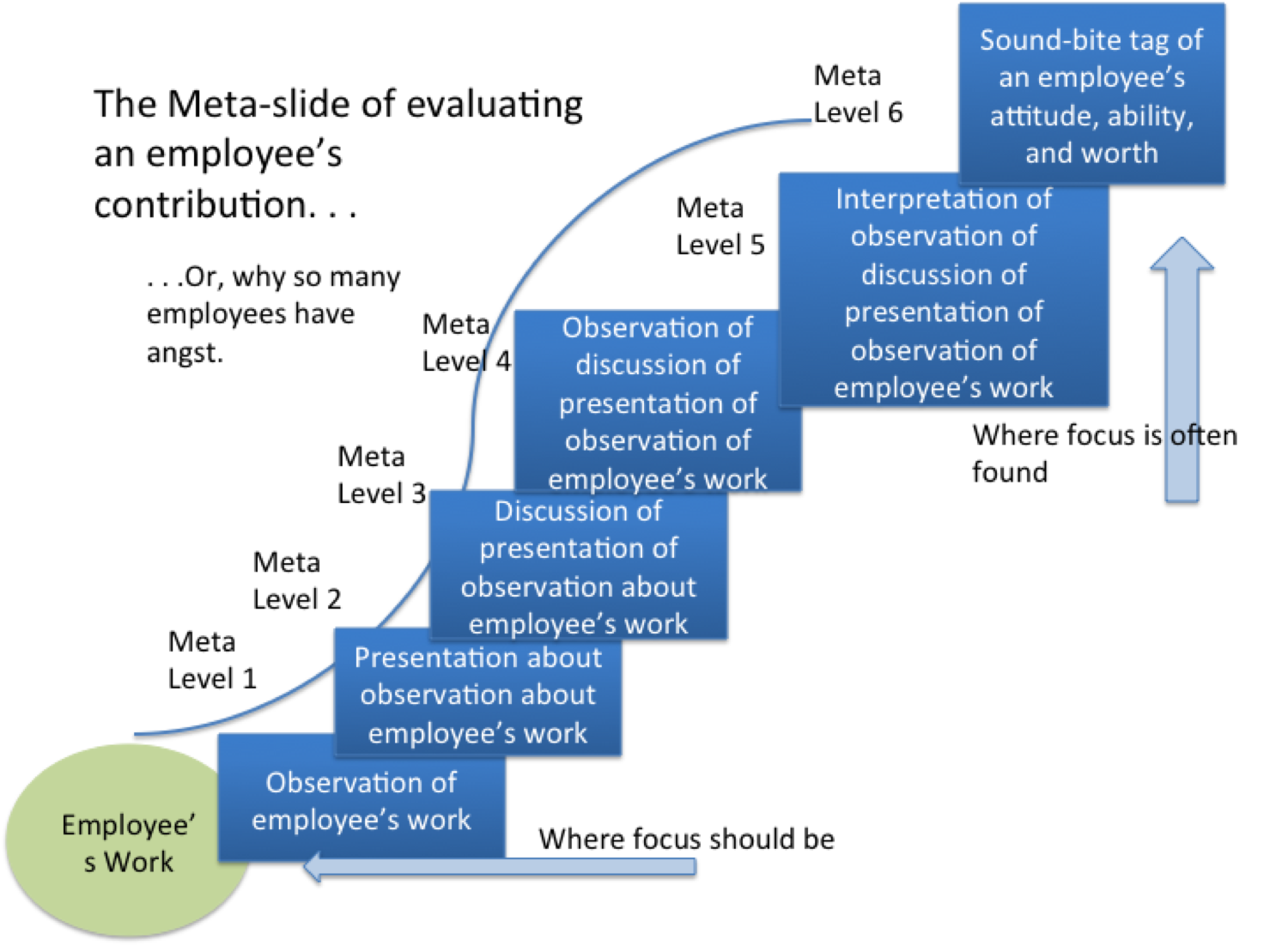

The discussion is inevitably a summary statement of everything an employee has done through the year, and that summary statement cannot possibly be true. In the “stack rank” discussion, a certain amount of meta-analysis of the employee’s performance and worth is required. Here’s what I mean:

Imagine the conversation with managers, managers of managers and levels above that. The conversation, the further it goes up the management chain, becomes less and less about the employee’s work, and more and more about perceptions and interpretations about the employee’s work. When you get two or three levels – or more — above the employee’s level, knowledge and observation of an employee’s work and output becomes absurdly thin. It is reduced to a sound-bite. Yet the person who is in charge of making the decision is the one furthest from the employee.

When employees know about these kinds of discussions, they have lots of angst, because it ultimately doesn’t matter what they do at work. It matters more about how the interpretation of their work gets re-interpreted through many filters, impressions, political machinations and innuendo.

What is most likely to happen is that the manager who advocates the loudest, or has the most charisma, is most politically “in” with the big boss, or has the most persuasive ability, is able to argue in favor of the “high performers” on the team. The manager who does not make forceful arguments, who cannot summarize eloquently, or simply doesn’t have the advocacy for his employees will inevitably have the “low performers.”

Don’t get me wrong, there are higher performers and there are lower performers in any work context, but when it gets determined in a once-a-year meeting where assertions, evaluative summaries, and decisions are made quickly and on limited information, the things that determine high performance and low performance are not necessarily the things that determine the outcome of the meetings. Promotions, raises, bonuses, and the like, are not necessarily correlated to the employee’s output, but is correlated to the meta-impressions that managers, managers of managers, and up the chain.

For an opposing view, here is an article that argues that stack ranking works, and achieves an “impressive” 16% increase in productivity. I would argue that the same effect of increasing productivity could be achieved by good management design, in which the manager who is responsible for and able to performance manage employees who are not performing the job duties, rather than using a comparative tool against all employees based on impressions and impressions of impressions. Why wait to compare employees, when the manager who is closest to the employee should be capable of directly observing, providing performance feedback, and addressing underperformance issues, and in the process increase the ability of the workforce to get the job done. If it is determined that the employee can’t do the job, performance management provides a means for finding a new situation for the employee. It’s much closer to the actual performance of the employee, targeted to the needs of the organization, and is not impressions at the higher level of the organization.

Does your organization attempt to stack rank? Is it done yearly? With all of the managers in a room together making arguments? How have you seen this done well?

Related articles:

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

Employee strengths and weaknesses discussions should be purely strategic — with examples!

Five reasons why focusing on weaknesses with employees is absurd and damaging

Bonus! Five more reasons why discussing weaknesses with employees is absurd and damaging

Helpful tip for managers: Keep a performance log

What inputs should a manager provide performance feedback on?