Management Design: A proposed design so that new managers embrace learning management skills

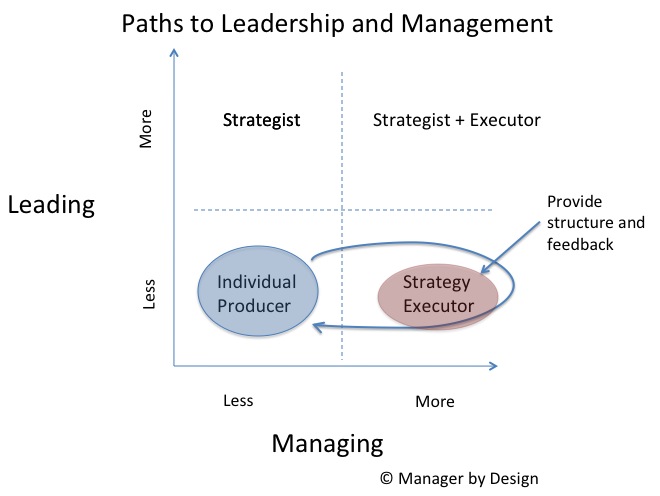

In my previous article, I discussed how an improved design would be to have structure and feedback provided to those who take on a leadership/strategy role, however temporary. This way, they learn strategy while doing strategy. Seems simple enough, but how often is it done?

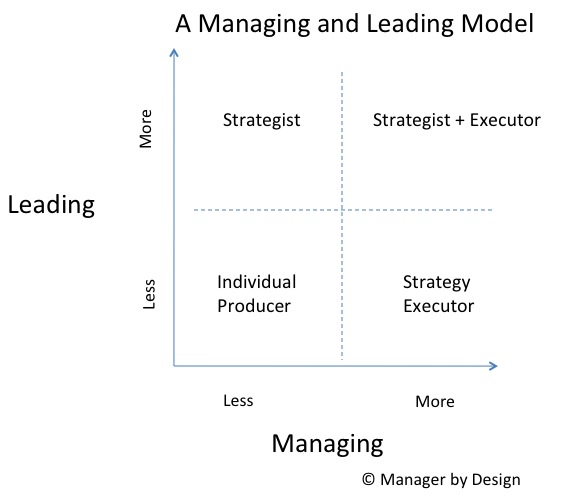

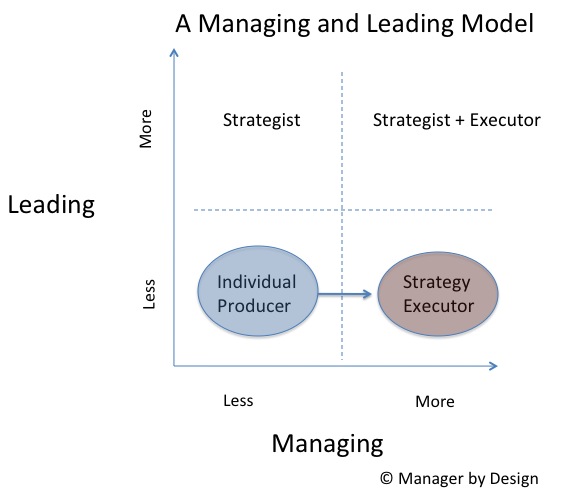

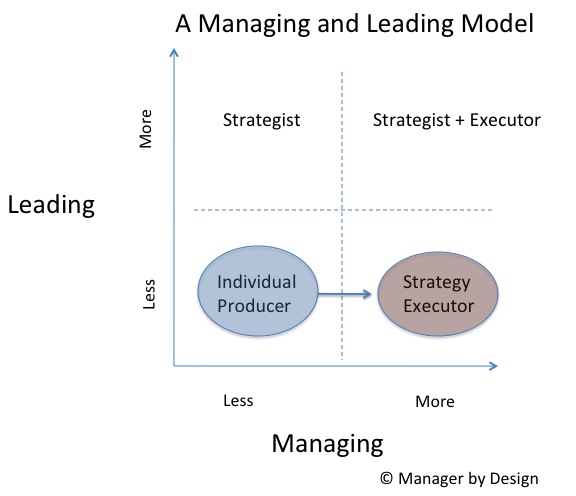

Now let’s transition the discussion away from leaders and to managers. In the Manager by Designsm leadership and management model, we can see how managers can learn their role using structure and feedback, and that it is possible to loop into the role and back out of it:

If someone goes into a team management role, they reason they have done this is to assure some sort of strategy execution. Sounds pretty important! So this sounds like a design requirement – makes sure someone is good at strategy execution.

Management Design: Structure and Feedback in a focused area of leadership

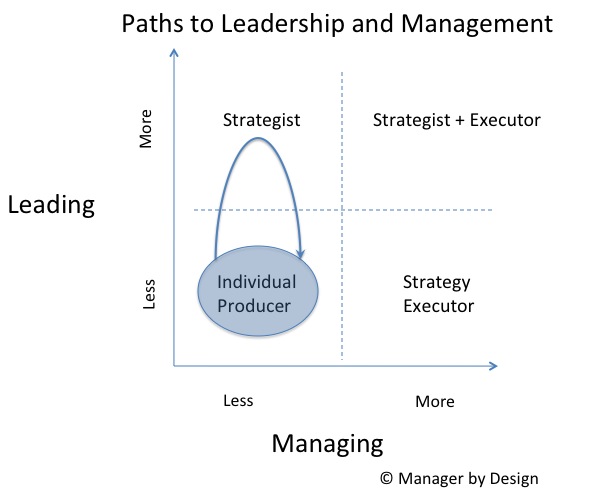

In my previous article, I propose a design that allows for a more systemic and purposeful way of developing managers and leaders. The basic idea is to provide leadership opportunities (setting strategy) and management opportunities (executing the strategy) without conflating both.

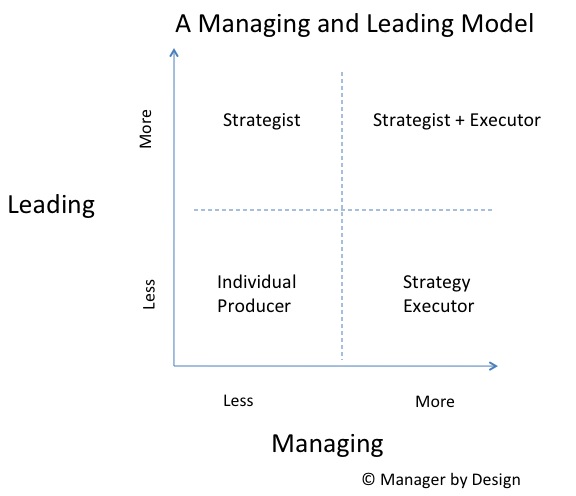

Here’s how it looks in the Manager by Designsm leadership and management model:

Under this model, the design is to identify people who are good at strategy, identify people who are good at strategy execution (management) and make sure that they are good at either strategy or strategy execution.

The same individual can try out both paths – if that individual is considered some sort of amazing performer – but this design is intended to find lots of people who are good at leadership and management, not just that magical super-performer as the current designs seem to be skewered toward.

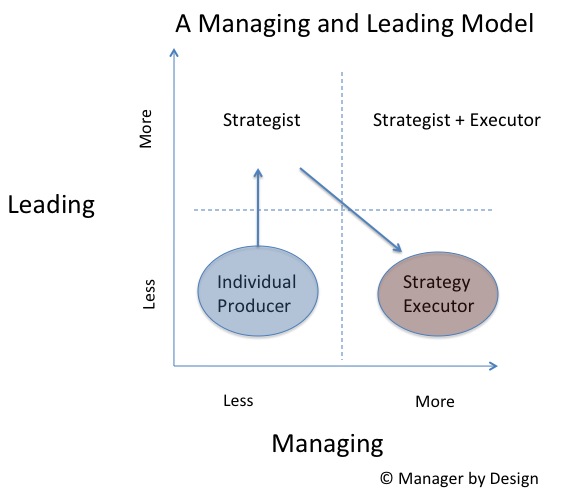

Management Design: An alternative path to management and leadership: Loop in and out

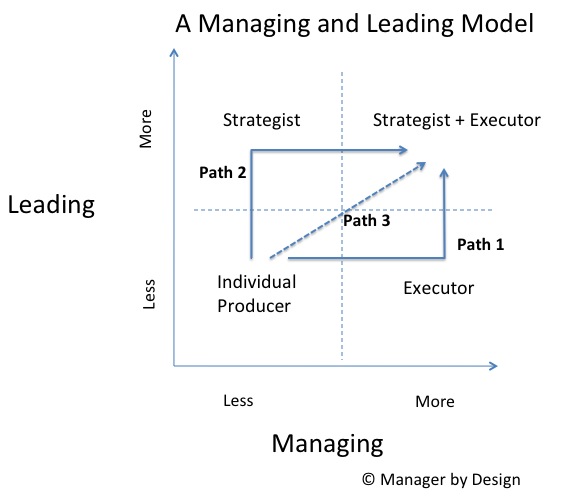

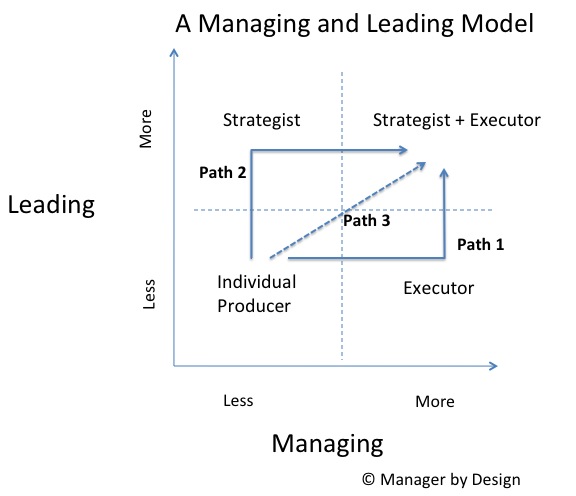

When looking at the Manager by Designsm leadership and management model, we can see some opportunities for better management design. Using the model in my previous article, I note that there are three common paths for creating managers and leaders (the two concepts often get conflated – the model attempts to differentiate). Here are the three paths:

What I find interesting about this view is that, according to this model, the paths all conclude with the individual being both a strategist and a strategy executor. In short, the paths imply the person has two jobs: Coming up with the ideas and seeing the ideas through.

These appear to be two entirely different skill sets, and skill sets that should be valued separately. There are certainly some people who can do both strategy and strategy execution well, but, really, how many? And do people who like to strategize also like to manage a team? Maybe sometimes, but not always.

So it would be important to find out, wouldn’t it? Let’s say you have someone in your organization who is very good at strategy. That sounds like something that would be valuable to many organizations. How do you find out? Does that population come from the “Strategy Executor” group? Or would it come from the individual producer group?

And once that strategist is identified, is it a full time job? Or do you make it one by transforming the strategist into a strategist + strategy executor?

In the current management design, the most common action is to look for the strategists from the management group (strategy executor group) (path 1 or 2 above).

There are a few of problems with this “design” (or perhaps an accidental by-product of ingrained organizational habits):

- This seems to limit the population of possible strategists as coming from strategy executors

- It sublimates the act of team management by devaluing excellence in team management

- Setting strategy is a part-time job, being shared with strategy executor.

In looking at path 3, it assumes that strategy is a springboard to management, and that the skill of setting strategy isn’t “enough” of leadership, and requires immediately halving this role to include managing a team.

So all of these “designs” appear to have inherent risks, which includes asking a leader to lead in a way that they aren’t good at, and asking a manager to become a leader/strategist.

So what are alternate paths? Here are a few that would seem less risky to me, and allow people and organizations to see what they are good at.

In this design, you have a means for people to hone their skills in what can be considered two different skill sets – strategy and strategy execution. In doing this, they can focus on the aspect of what they are being asked to do without the clutter of conflating leadership and management.

Management Design: The Designs we have now: The paths to management and leadership

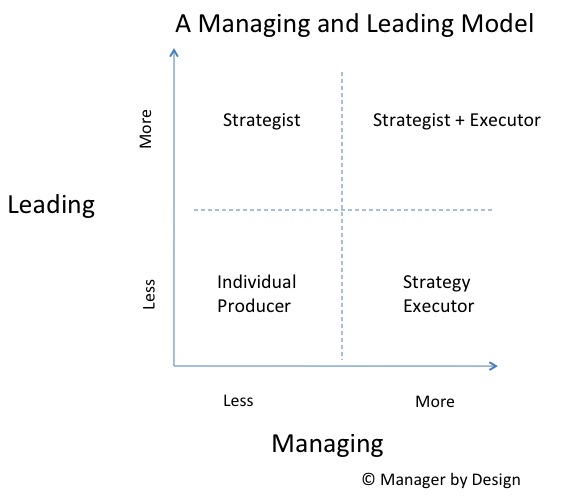

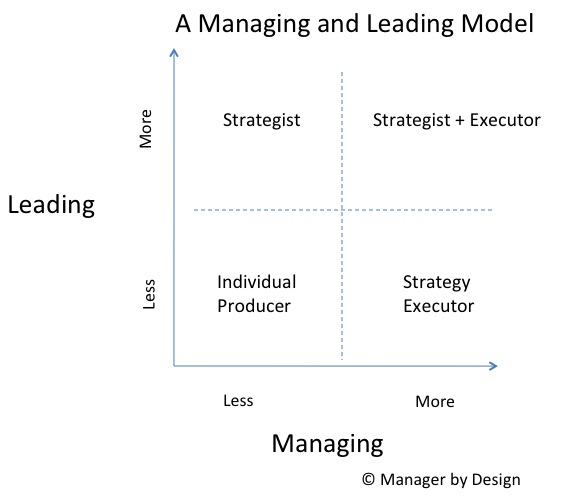

This continues a series of articles that examines the differentiation between management and leadership by looking at a model I created that specifies the difference between management and leadership:

In this model, I make the point that it is possible to be a leader without being a manager, and a manager without being a leader. The main differentiation is the action of setting strategy and the action of executing the strategy.

At the same time, we normally conflate leadership with doing both strategy and execution. In my model, that is fine, but the leadership element is still tied to strategy and the management element is still tied to execution. If you want people in your organization to be both strategists and executors of strategy, then this model is useful.

So let’s look at how that can be. Here are the three paths that are typically considered how someone becomes a do-it-all leader/manager (or, in my model, a strategist + executor).

Path 1: Become a manager, then start doing strategy

In this path, someone becomes a manager of a team they probably served on. They are charged with keeping an existing strategy going, and making sure that team has the existing level of productivity. At a certain point, that manager steps out of that role and starts coming up with new strategies and direction for the organization, while continuing to be a manager of a team or organization.

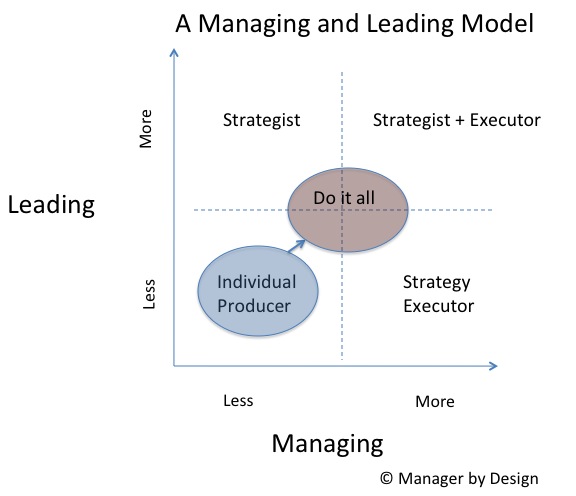

Current management design: The one with the ideas becomes the manager

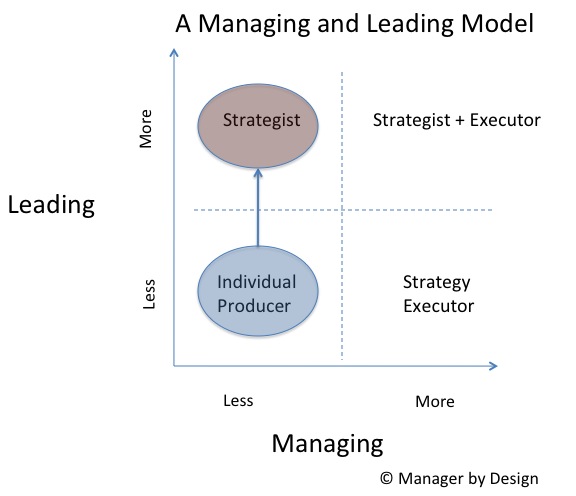

In my previous articles, I showed why managers are often resistant to change or are bad at leadership – by design. In today’s article, I’d like to walk through another common scenario – the leader who then has to manage.

I’ve created a model that shows the difference between leadership and management.

In this model, it allows for an individual person without a team to demonstrate leadership. If they are involved with setting the strategy for an organization, they are a leader. Oftentimes this is the person with the idea, and that person does a lot of work to spread the idea, get support for the idea, and convince other parts of leadership and individual producers of the need to pursue the idea. If that idea actually gets executed, it sure looks like that person is a leader – the person leads by being out in front of an idea, and leads by making sure the idea got into the hands of those who can do something about it.

So that shows how someone can become a leader without managing a team!

I love this scenario, because it shows that someone in an individual contributor role can be considered a serious leader in an organization. There are many people like that in an organization, and this kind of path to be a “strategist” shows career growth that can provide terrific value to the organization. It also shows that the strategist does not have to be the strategy executor (a.k.a., manager) to be a leader in an organization.

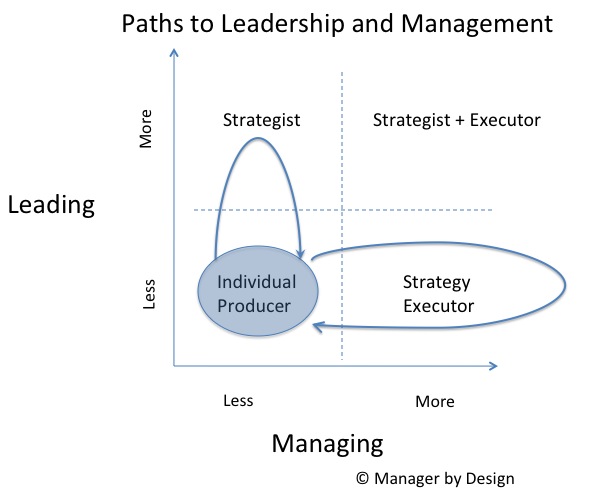

Now, here’s the problem. Many times organizations say, “This is a great leader!” Then they put that person in a manager role:

We’ve seen this frequently in organizations. When someone shows leadership, they are given a team to execute that strategy. It is a common marker of success for that individual. Here’s your team – now go do it!

Management Design: The Designs we have now: Part time strategist, part time manager

In my previous article, I discuss a management/leadership model I developed that shows how managers are resistant to changing strategies, and this is often by poor design. Here’s how it looks:

Even though this is a common path for people to become managers, there is a design flaw for those organizations that change their strategy. The managers are focused on and understand a single strategy, and, in this visualization, aren’t involved in, or aware of possible other strategies that follow.

Now lets look a slightly different path that is also common:

I call this the “do it all” scenario. It kind of makes sense, as you can see that when someone gets promoted from an individual producer role to a manager role, they are then required to show leadership, which involves developing strategy skills as well as people management skills.

Management Design: The designs we have now – Manager knows and supports only one possible strategy

In my previous article, I showed a model I created that identifies the difference between being a leader and a manager. Here it is:

In this model, the manager that I typically think of when writing about managers is in the lower right corner – a manager who is a “Strategy Executor.” The organization that the manager works for has a strategy, and the manager makes sure that this strategy is executed. This manager typically has a team of people in some capacity (either direct reports, virtual, outsourced vendor) to make sure the strategy is executed.

As an example, if you are a Training Manager, then the strategy is that the organization is using “Training” as a means to help the organization run better. “Training” is the Strategy, and the Training Manager is needed to execute that strategy.

So the training manager has to make sure the training is executed. That means there needs to be budget, a team of people and facilities to get this done somehow. That’s the manager’s job – use these resources to execute the “Training” Strategy.

But how does one become a strategy executor, a.k.a., manager? There are various paths.

The most commonly thought of path is the following:

- Someone is really good at being an individual producer, and the manager role opens up, and they get the job as the manager. That individual producer is now the strategy executor. Here’s how it looks on the model:

This seems to fit in the popular conception of how people become managers, but under this model, you can see a potential design flaw. The person becomes a manager without having been involved with the strategy development. In the case of the Training Manager, the strategy executor will be executing the “Training Strategy” without really knowing what went into the development of that strategy.

A model to show the difference between managing and leading

The Manager by Design blog seeks to provide great people management tips and awesome team management tips. The focus of the blog is on management, but the question is – what is the difference between leadership and management? There are hundreds of great books on leadership, and there are many resources that work to delineate the difference between managing and leading. For there purposes of this blog, here is the model I have that demonstrates the difference between managing a leading.

Let’s take a look at the model:

In this model, I’ve put out a grid that puts managing on the x-axis and leading on the y-axis to demonstrate their inter-relationships and where they separate.

In the lower left quadrant (“Individual Producer”), you have a role that requires neither managing nor leading. I call it the individual producer. If that individual producer produces something (analyses, a product, a sale), then that person has done her job, and is doing well at the job. This person is neither managing nor leading, but still producing, and contributing. Every organization needs lots of this!

Managers: Know your change events and track these

When you are a manager, one of the things that you are responsible is the ongoing improvement of your team and how it operates.

Now, with that expectation set, are you tracking the “change events” that account for and assess this?

Change happens on a team and in a group all the time. In fact, it happens so often that it is easy to lose track of all of the change that is happening.

Here are sample “change events” that could constitute change on your team:

- A new person or joins the team or someone leaves the team (or many people join or leave the team)

- A new budget is implemented

- Your organization or your team launches a strategy

- There is a process improvement or process change

- There is a change in scope of work

- A new project starts or an old project ends

- There is a new environment or element to the work environment (change in office space or new equipment)

Some of this change is instigated by the manager, and some of it is implemented by external events, either from above or by the passage of time. It’s all change, and it needs to be understood as such.

So the first task of understanding change is to track these events. If you don’t do it as a manager, perhaps someone on your team can track these events. Having these change events documented and tracked creates a better understanding of what your team is handling.

So here are some suggesting things to track for your team change:

- Item number

- Source of change

- Change description

- Initial date of learning of change

- Expected positive impact

- Expected negative impact

- Who is responsible for delivering the change

- Who is involved

- Change plan location

- Change implementation / assessment date

Here’s what it may look like on a spreadsheet

| Item Number | Change description | Source of change | Initial Date of learning of change | Expected positive impact | Expected negative impact | Who is responsible for delivering change | Who is involved | Change plan location | Change implementation / assessment date |

| 1 | Marci leaves | Marci | 6/1/2011 | Opportunity to identify emerging team needs and hire to it | Lose Marci’s skill set | Manager hiring | Manager, HR, Team Members | Hiring process site | 7/1/2011 (replacement hired) 12/1/2011 (up to speed) |

| 2 | New quality assurance program | Manager initiated | 3/1/2010 (kick off of implementation) | Improved quality | Resistance/inertia of prior system, less efficiency | Alex | All team and partner teams | Team site : projects | 12/1/2011 (program implemented) 3/1/2011 (assess quality) |

| 3 |

What to do when someone on your team resists change (part 2)

In my previous article, I describe the importance of not attacking a change agent, but instead taking steps to manage the change, not the change agent. Many managers receive “feedback” that is resistance to change, and then turn around and give that feedback to the change agents, implying that the manager doesn’t actually want the change agent to instigate the change.

The first five steps to this were: 1. Listen 2. Document the issue 3. Track the issues. 4. Delay in responding to them 5. Look at the issues as a team.

Today, I provide tips on what to do next:

6. Communicate your findings – the more targeted the better

You typically know the source of the resistance/complaint. You tracked it, right? Now you can respond directly to that person. Explain what you did (discussed it as a team) and what you plan to do (keep going with the change, most likely). I am not a fan of communicating broadly the list of concerns and the responses, because it is somewhat akin to public feedback. By communicating broadly, you are trying to adjust the thinking for a specific person via communicating with a broad group. This creates unintended consequence of changing the broad group’s thinking when it isn’t necessarily a problem. It’s better to circle back to the person who expressed the concern in the first place. If there is a network of people who believe the same thing, that person then gets to address the results.