Management Design: How to include your managers in the strategy development process and develop leaders at the same time

If your organization has a strategy, it’s probably important that your managers – the strategy executors – be able to understand, articulate, and interpret the strategy well. If not, then this is bad management design. The Manager by Designsm blog’s leadership/management model makes the distinction of managers as strategy executors and leaders as strategy developers. So it is important that the managers be able to understand, articulate and interpret the strategy well.

One good design is to include managers in the strategy development process. It looks something like this:

But this should be designed to be done smartly and not in a haphazard way. An example of being sloppy in the design of “including the managers” is through having the management team regularly sit in on leadership meetings. This is a big waste of time, and would no doubt chart as low quality meetings.

Instead, the managers’ involvement needs to have the following elements:

a) Specifically selected managers (not all managers)

b) Be focused specifically on the strategy development process (not all leadership meetings)

c) The role needs to be defined with expectations to participate included (not just sit in)

d) It needs to be articulated that managers are assisting with the strategy development process (as opposed to, say, “You’re attending the ‘Leadership Meetings’”)

e) There needs to be an end to this process so the manager can go back to managing (not a standing invitation).

As a bonus, if the strategy development process is an involved one, the managers involved would be temporarily relieved of their duties as “strategy executor” manager, with the understanding that they will go back to this role.

In this process, not only will the manager become better at managing, in that she (and her employees) will be able to articulate and interpret the strategy better, but she is also is aware of the strategy development process as a specific process, allowing her to become a better “leader” in addition to being a better manager.

Perhaps that manager will someday make a transition to being a “leader” and will be able to do – when in that leadership position — the following things:

- Articulate that there is a strategy development process

- Describe what that process is

- Replicate it and improve upon it when in the role of strategy developer

- Include the managers in the process

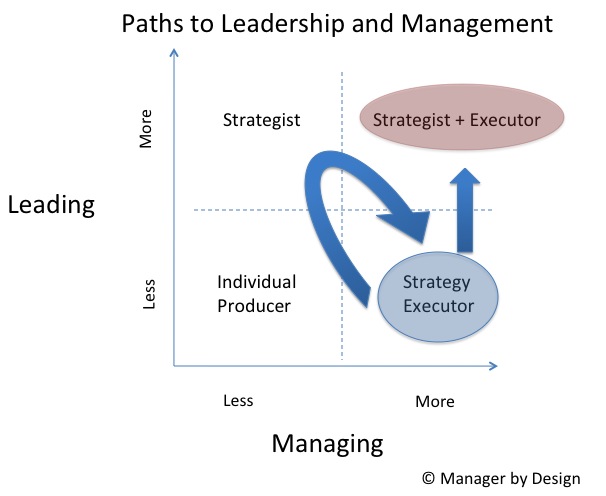

All of this while doing work that assists the current organization needs, and done on the job and not in a separate, abstracted training class. So the “leadership development” of the manager would look something like this:

The manager learns how to manage (strategy execution) and then learns how to lead (set strategy) and understand the difference between these actions, versus conflating these myriad of actions all as “leadership.”

As an extra bonus to including a manager in the strategy development process, the strategy itself will likely be better, as she can provide the needed perspective from the “strategy executors” on what they need to execute the strategy, and whether the strategy is going to work. As a double extra bonus, she will be to assist with the strategy implementation to other managers, assist with the ongoing interpretation to the other managers, all things that seem to assist with the current needs of the organization. In short, this is “leadership development” while doing the current job better.

The alternative I have seen is to have leadership development happen external to the job – -usually through a leadership development class or series of classes. These are effective at introducing the concepts, but do not allow for immediate applicability. This time delay will usually mean limited (if at all) application of the concepts. If you need classes at all, a better design would be to have the “strategy process” be taught to the manager (strategy executor) just prior to participating in the strategy development process.

Does your organization include the managers in the actual strategy development process? Or does it rely on developing its leadership through either classes or “sink or swim” methods?

Related Articles:

Management Design: The Designs we have now: The paths to management and leadership

Management Design: An alternative path to management and leadership: Loop in and out

Management Design: Structure and Feedback in a focused area of leadership

A model to show the difference between managing and leading

Do your managers know the strategy of your organization?

Tips for how your managers can better execute strategy

Tips for how your managers can better understand your strategy

How do managers learn strategy?

Management Design: A proposed design so that new managers embrace learning management skills

Tips for how your managers can better understand your strategy

The Manager by Designsm blog has recently been focusing on how managers – or “strategy executors” – can better align their work to . . . strategy executors. The Manager by Design blog believes that managers are strategy executors and leaders are the strategy developers. In my previous article, I provide tips for infusing the strategy into the manager’s goals/objectives, and testing whether the managers – and their employees — can articulate what the strategy they are supposedly executing is.

But managers need better performance support than simply putting the strategy in their goals. You want to make sure your managers are capable of making good interpretations of the strategy, and have some sort of specific and immediate feedback on these interpretations. Makes sense, huh? But how would you describe how your organization provides ongoing support for helping the manager interpret the organization’s strategy?

Here are some tips for improving this:

1. Provide access to those who developed the strategy

It’s one thing to have a group that develops the strategy, and it’s another to have that group accessible to help interpret the strategy. A strategy is, in essence, a summary statement of intent by leadership, so there are times when those who are carrying out the intent need to check in on whether their understanding of the intent is correct. To help with this, check the communications paths that are available to your managers. Do they have access to those who went through the strategy development process? Do they even know who developed the strategies? On the flip side, do people in the group who developed the strategy know who will be executing the strategy? If not, then there is a much lower likelihood that the strategy will be understood or interpreted by the strategy executors.

2. Include some managers in the strategy development process

First, I’m assuming that there is a strategy development process in the organization. If this is not the case, then perhaps it is time to consider one. If you do have such a process, how do you include the managers in the process? Many times the “inclusion” is the “announcement” of the strategy as a handoff to the managers, and that is it! But this, too, is a low percentage proposition in assuring your managers can understand, re-articulate and make good decisions based on the strategy.

One way to improve this “handoff” is to identify how managers are included in the process of strategy development when the process takes place. You don’t have to include all managers, and it doesn’t have to be the same managers each time the strategy development takes place. In doing this, no only do you assure that you have management inclusion, but when the strategy is “announced”, there are resources (see point 1) that are nearby that can better articulate the intent of the strategy and how it should be interpreted.

There are other benefits for including managers in the strategy process. In my next article, I’ll provide tips on how to include the managers (a.k.a., strategy executors) in the strategy development process and what some benefits of this process are.

Related articles:

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

A model to show the difference between managing and leading

Do your managers know the strategy of your organization?

Tips for how your managers can better understand your strategy

How do managers learn strategy?

Management Design: The designs we have now – Manager knows and supports only one possible strategy

Management Design: The Designs we have now: Part time strategist, part time manager

Current management design: The one with the ideas becomes the manager

Tips for how your managers can better execute strategy

The Manager by Designsm blog defines “management” as being the role of strategy execution, assuming your organization has a strategy. (See here for more on this topic of the management vs. leadership model). So one key to great management would be to assure managers are aware of the strategy, can articulate the strategy, make good interpretations of how the strategy translates to actions, and give feedback on how to improve the strategy.

How to make sure this happens? You want your managers to be good at strategy execution, and part of this is being able to understand and appreciate the strategy that is being executed. As part of the management design, you want to make sure that this understanding, articulation and evaluation of strategy execution is included into the manager expectations.

Have you ever had a manager who wasn’t able to really articulate why they were doing the things they were doing it? Instead, they are enforcing something? Or actively subverting the strategy? These are often bad managers. If they are bad at understanding the overriding strategy, their decision-making will be poor, their credibility with the workforce will be limited, and the results will not be aligned with the strategy.

Here are some management design ideas to help your organization have managers who are more aware of and more supportive of the strategy:

1. Create manager objectives aligned to the strategy

The first thing to try is to make sure the objectives of the strategy group (or wherever the strategy is coming from) — perhaps the strategy itself — are articulated in the manager’s objectives. Read more

How do managers learn strategy?

The Manager by Designsm blog believes that there is a distinction between management and leadership. Management is tied to strategy execution, and leadership is tied to strategy development. Having a better understanding of this differentiation can help improve the “designs” in which organizations develop both managers (strategy executors) and leaders (strategists). Sloppy management design, in turn, is when you expect both management and leadership skills get developed all at once, or are delivered to your organization via recruited “talent.”

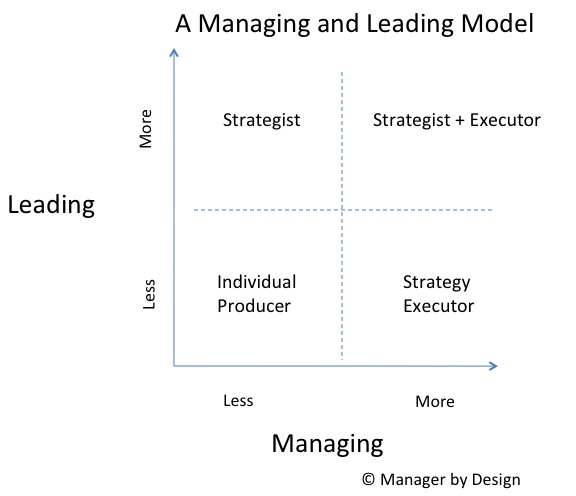

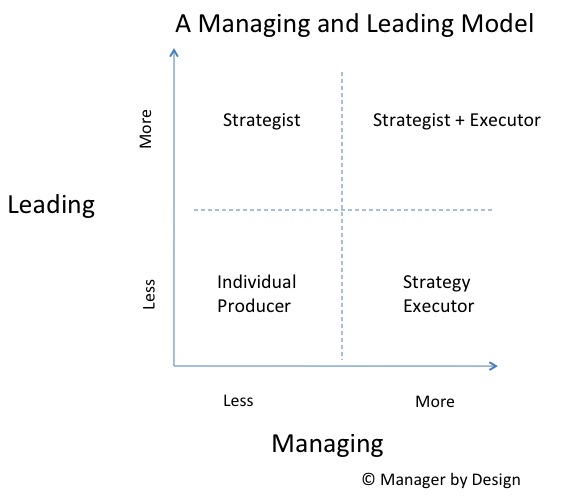

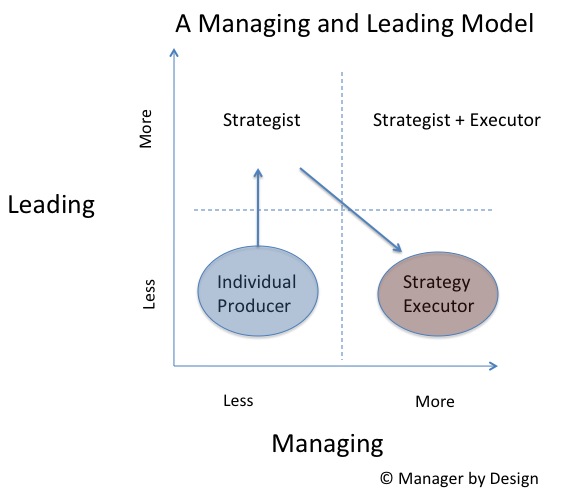

Here is the Manager by Design leadership and management model:

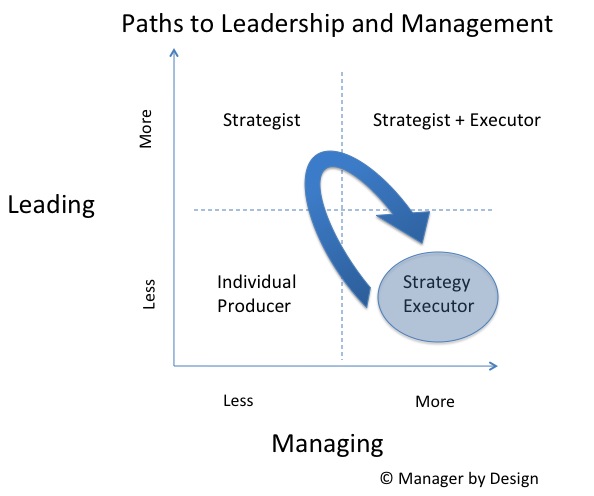

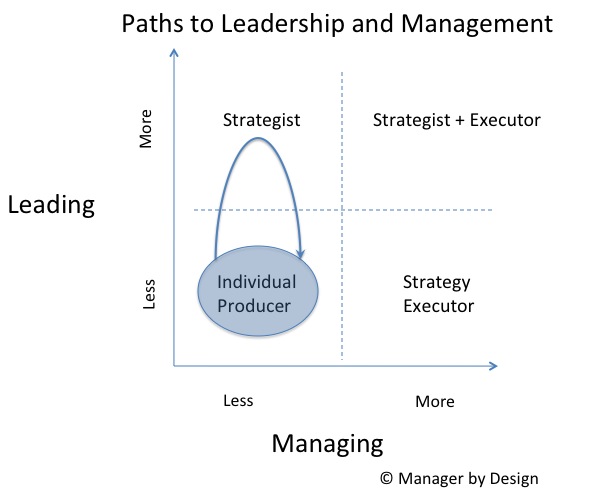

In the commonly held notion of “becoming a manager”, the path looks like this:

In this notion, the individual producer becomes in charge of the team doing the producing. The new manager is in charge of “strategy execution.” This is a fine model if there is some structure and feedback in performing the new managerial role, and a terrible model if there is no structure and feedback. It all depends on the management design of the organization. Are the managers designed to be great? Or are they left to their own devices in determining and creating their management practices?

Assuming that the manager has guidance in the core people management practices, there is another potential flaw with this scenario: The manager does not develop strategy skills or does not appreciate the act of developing strategy.

If your organization is looking to create leadership capability (in my model, the “develop strategy” quadrant), then there are a few paths that can be designed in to help with this potential design flaw while doing the job of managing.

1. Create objectives aligned to the strategy and clean handoffs between the strategists and the strategy executors

2. Assure and encourage access to the strategists and articulation of the strategy

3. Temporarily and cleanly have the manager participate in the strategy process

4. Provide the structure and feedback in developing the strategy for the strategy execution

Having elements like these in your management design will improve how managers who are in charge of strategy execution understand better the strategy, and, in turn, execute the strategy. The emerging field of Management Design must take this into consideration, and create designs that encourage the interaction and handoff between strategy and strategy execution.

It is the goal of the emerging field of Management Design to encourage managers to seamlessly execute the strategy of an organization. If it is being done poorly or haphazardly, then you will not get strategy execution, a main task of management. You may get some sort of execution, but will you get strategy execution?

In upcoming articles, I’ll discuss these potential designs for assuring that managers know the strategy, contribute to the strategy process, and develop their own strategy setting skills.

Related articles:

Management Design: The designs we have now – Manager knows and supports only one possible strategy

Management Design: The Designs we have now: Part time strategist, part time manager

Current management design: The one with the ideas becomes the manager

Management Design: The Designs we have now: The paths to management and leadership

Management Design: An alternative path to management and leadership: Loop in and out

Management Design: Structure and Feedback in a focused area of leadership

Management Design: A proposed design so that new managers embrace learning management skills

Tenets of Management Design: Focus on the basics, then move to style points

Management Design: A proposed design so that new managers embrace learning management skills

In my previous article, I discussed how an improved design would be to have structure and feedback provided to those who take on a leadership/strategy role, however temporary. This way, they learn strategy while doing strategy. Seems simple enough, but how often is it done?

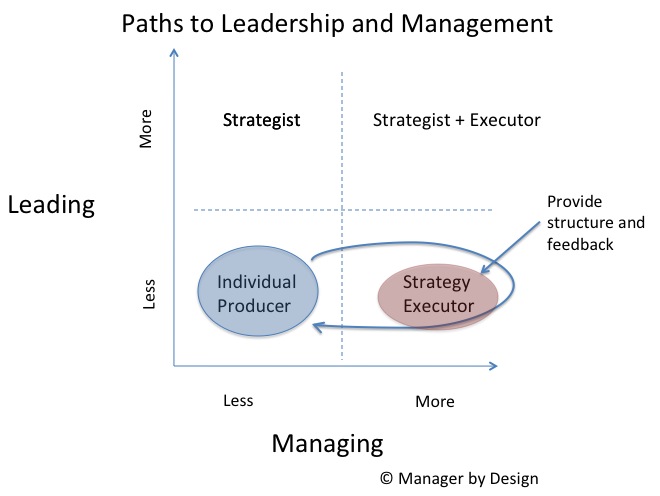

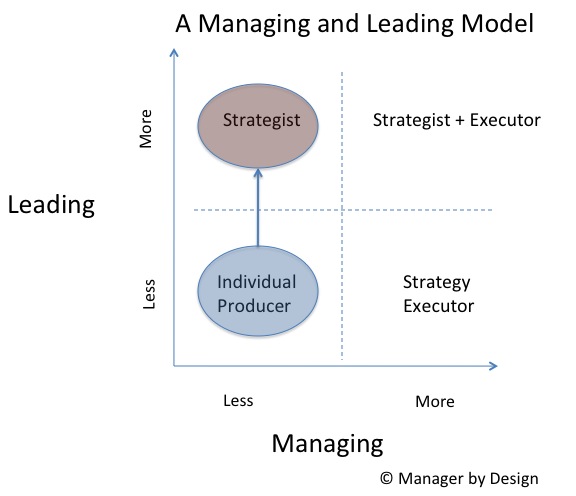

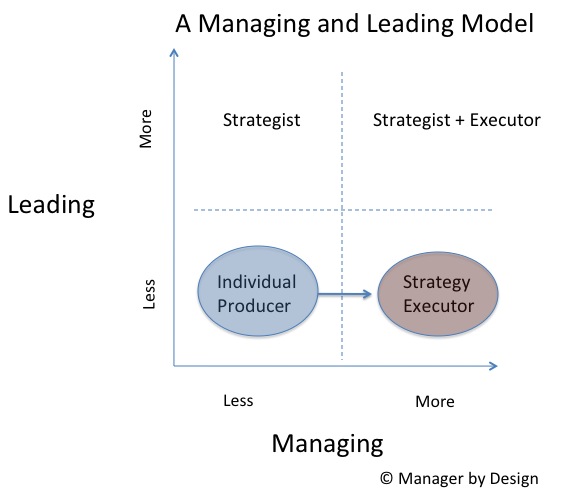

Now let’s transition the discussion away from leaders and to managers. In the Manager by Designsm leadership and management model, we can see how managers can learn their role using structure and feedback, and that it is possible to loop into the role and back out of it:

If someone goes into a team management role, they reason they have done this is to assure some sort of strategy execution. Sounds pretty important! So this sounds like a design requirement – makes sure someone is good at strategy execution.

Management Design: Structure and Feedback in a focused area of leadership

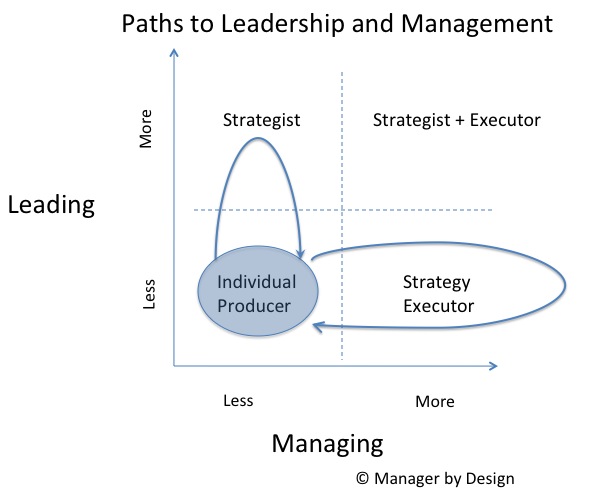

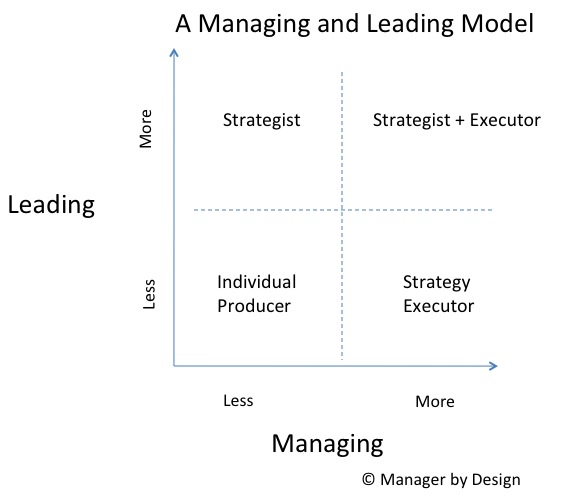

In my previous article, I propose a design that allows for a more systemic and purposeful way of developing managers and leaders. The basic idea is to provide leadership opportunities (setting strategy) and management opportunities (executing the strategy) without conflating both.

Here’s how it looks in the Manager by Designsm leadership and management model:

Under this model, the design is to identify people who are good at strategy, identify people who are good at strategy execution (management) and make sure that they are good at either strategy or strategy execution.

The same individual can try out both paths – if that individual is considered some sort of amazing performer – but this design is intended to find lots of people who are good at leadership and management, not just that magical super-performer as the current designs seem to be skewered toward.

Management Design: An alternative path to management and leadership: Loop in and out

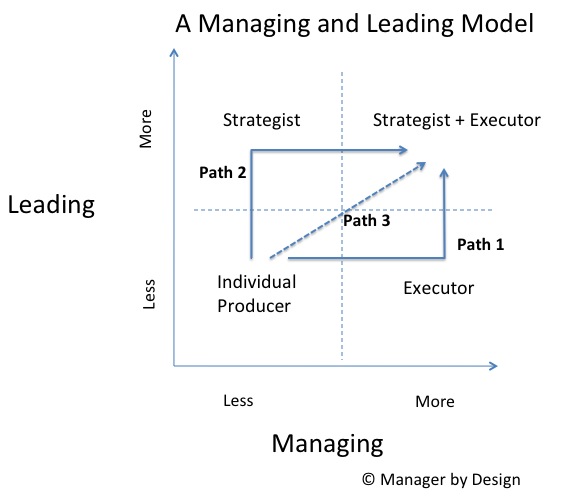

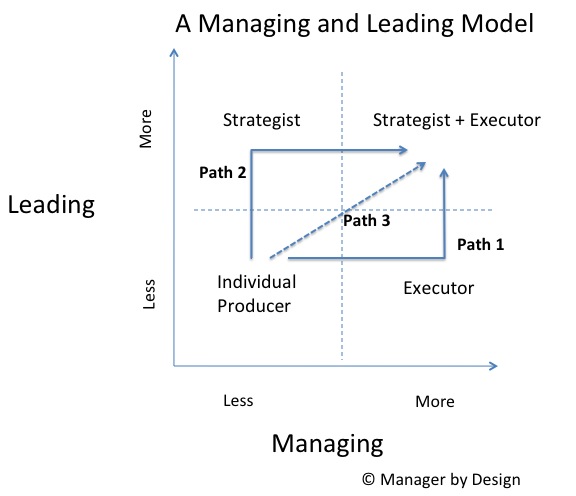

When looking at the Manager by Designsm leadership and management model, we can see some opportunities for better management design. Using the model in my previous article, I note that there are three common paths for creating managers and leaders (the two concepts often get conflated – the model attempts to differentiate). Here are the three paths:

What I find interesting about this view is that, according to this model, the paths all conclude with the individual being both a strategist and a strategy executor. In short, the paths imply the person has two jobs: Coming up with the ideas and seeing the ideas through.

These appear to be two entirely different skill sets, and skill sets that should be valued separately. There are certainly some people who can do both strategy and strategy execution well, but, really, how many? And do people who like to strategize also like to manage a team? Maybe sometimes, but not always.

So it would be important to find out, wouldn’t it? Let’s say you have someone in your organization who is very good at strategy. That sounds like something that would be valuable to many organizations. How do you find out? Does that population come from the “Strategy Executor” group? Or would it come from the individual producer group?

And once that strategist is identified, is it a full time job? Or do you make it one by transforming the strategist into a strategist + strategy executor?

In the current management design, the most common action is to look for the strategists from the management group (strategy executor group) (path 1 or 2 above).

There are a few of problems with this “design” (or perhaps an accidental by-product of ingrained organizational habits):

- This seems to limit the population of possible strategists as coming from strategy executors

- It sublimates the act of team management by devaluing excellence in team management

- Setting strategy is a part-time job, being shared with strategy executor.

In looking at path 3, it assumes that strategy is a springboard to management, and that the skill of setting strategy isn’t “enough” of leadership, and requires immediately halving this role to include managing a team.

So all of these “designs” appear to have inherent risks, which includes asking a leader to lead in a way that they aren’t good at, and asking a manager to become a leader/strategist.

So what are alternate paths? Here are a few that would seem less risky to me, and allow people and organizations to see what they are good at.

In this design, you have a means for people to hone their skills in what can be considered two different skill sets – strategy and strategy execution. In doing this, they can focus on the aspect of what they are being asked to do without the clutter of conflating leadership and management.

Management Design: The Designs we have now: The paths to management and leadership

This continues a series of articles that examines the differentiation between management and leadership by looking at a model I created that specifies the difference between management and leadership:

In this model, I make the point that it is possible to be a leader without being a manager, and a manager without being a leader. The main differentiation is the action of setting strategy and the action of executing the strategy.

At the same time, we normally conflate leadership with doing both strategy and execution. In my model, that is fine, but the leadership element is still tied to strategy and the management element is still tied to execution. If you want people in your organization to be both strategists and executors of strategy, then this model is useful.

So let’s look at how that can be. Here are the three paths that are typically considered how someone becomes a do-it-all leader/manager (or, in my model, a strategist + executor).

Path 1: Become a manager, then start doing strategy

In this path, someone becomes a manager of a team they probably served on. They are charged with keeping an existing strategy going, and making sure that team has the existing level of productivity. At a certain point, that manager steps out of that role and starts coming up with new strategies and direction for the organization, while continuing to be a manager of a team or organization.

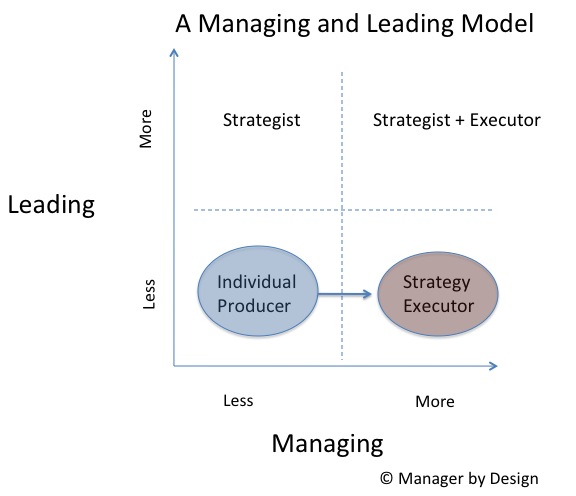

Current management design: The one with the ideas becomes the manager

In my previous articles, I showed why managers are often resistant to change or are bad at leadership – by design. In today’s article, I’d like to walk through another common scenario – the leader who then has to manage.

I’ve created a model that shows the difference between leadership and management.

In this model, it allows for an individual person without a team to demonstrate leadership. If they are involved with setting the strategy for an organization, they are a leader. Oftentimes this is the person with the idea, and that person does a lot of work to spread the idea, get support for the idea, and convince other parts of leadership and individual producers of the need to pursue the idea. If that idea actually gets executed, it sure looks like that person is a leader – the person leads by being out in front of an idea, and leads by making sure the idea got into the hands of those who can do something about it.

So that shows how someone can become a leader without managing a team!

I love this scenario, because it shows that someone in an individual contributor role can be considered a serious leader in an organization. There are many people like that in an organization, and this kind of path to be a “strategist” shows career growth that can provide terrific value to the organization. It also shows that the strategist does not have to be the strategy executor (a.k.a., manager) to be a leader in an organization.

Now, here’s the problem. Many times organizations say, “This is a great leader!” Then they put that person in a manager role:

We’ve seen this frequently in organizations. When someone shows leadership, they are given a team to execute that strategy. It is a common marker of success for that individual. Here’s your team – now go do it!

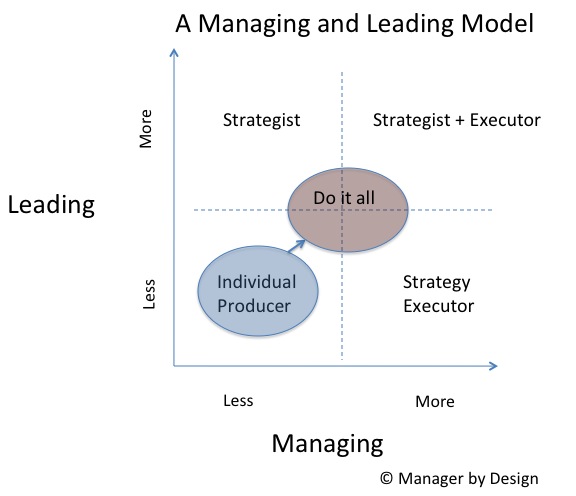

Management Design: The Designs we have now: Part time strategist, part time manager

In my previous article, I discuss a management/leadership model I developed that shows how managers are resistant to changing strategies, and this is often by poor design. Here’s how it looks:

Even though this is a common path for people to become managers, there is a design flaw for those organizations that change their strategy. The managers are focused on and understand a single strategy, and, in this visualization, aren’t involved in, or aware of possible other strategies that follow.

Now lets look a slightly different path that is also common:

I call this the “do it all” scenario. It kind of makes sense, as you can see that when someone gets promoted from an individual producer role to a manager role, they are then required to show leadership, which involves developing strategy skills as well as people management skills.