What to do when someone on your team resists change (part 2)

In my previous article, I describe the importance of not attacking a change agent, but instead taking steps to manage the change, not the change agent. Many managers receive “feedback” that is resistance to change, and then turn around and give that feedback to the change agents, implying that the manager doesn’t actually want the change agent to instigate the change.

The first five steps to this were: 1. Listen 2. Document the issue 3. Track the issues. 4. Delay in responding to them 5. Look at the issues as a team.

Today, I provide tips on what to do next:

6. Communicate your findings – the more targeted the better

You typically know the source of the resistance/complaint. You tracked it, right? Now you can respond directly to that person. Explain what you did (discussed it as a team) and what you plan to do (keep going with the change, most likely). I am not a fan of communicating broadly the list of concerns and the responses, because it is somewhat akin to public feedback. By communicating broadly, you are trying to adjust the thinking for a specific person via communicating with a broad group. This creates unintended consequence of changing the broad group’s thinking when it isn’t necessarily a problem. It’s better to circle back to the person who expressed the concern in the first place. If there is a network of people who believe the same thing, that person then gets to address the results.

Are you asking a change agent to make a change, and then resisting the change?

Many managers want to get great results. To do this, they seek and find high performers who drive toward these results. One way a high performer can achieve great results is through creating and implementing structures and processes that provide ongoing value and systemic improvement. Or, in other words, change.

The high performer is a change agent. This is what managers want. Managers want change for the better, and rely on the “high performers” to instigate and implement the change. That’s what makes them a high performer.

But there is a mistake that many current managers make in seeing this model through: They give feedback to the person instigating the change that there is resistance to the change. This is a flaw in current management design, and one that is all too common.

Here’s what I mean:

When change occurs in an organization, there inevitably will be complaints about the change. The complaints will be about whoever is instigating the change. It doesn’t matter if it is good or bad change, people somewhere in the organization will be resistant to the change. This is normal and part of the “change curve.” The complaints will be inevitably be about the person instigating the change. That was supposedly the high performer, who was encouraged by the manager to create the change.

Using perceptions to manage: How this undermines efforts for change

This is the latest in a series of articles about how using perceptions in managing a team can be a recipe for disaster.

Think about the manager who says, “There’s a perception that you expect too much of other people” or “There’s a perception that you are not very well liked.” This is the manager attempting to manage perceptions and not behaviors, and is something that needs to be banned from the manager’s vocabulary. I provide reasons here, here, here, here and here (there’s a perception that this is a very thorough series!).

In today’s article, I discuss how negative perceptions are often a symptom of positive change:

In a previous article I discuss the scenario of Arnold, a team member that provided suggestions and helped implement changes on a team that produced greater productivity and lower cost. In the process, there were some negative perceptions about Arnold, “You’ve done a lot of things since joining the team, but there’s a perception that you want to change things too fast, and that you expect the team to do too much.” Let’s take a look at what this means:

Citing perceptions often reveals change agents at work and then undermines them

If a manager can cite only negative perceptions of someone as the negative impact, then this could be an indicator that the person could actually a positive change agent in the workplace. Many people are resistant to change, and when someone brings it to the organization, that resistance will manifest as undifferentiated negative perceptions that quickly propagate through the organization. The actual change may be good and improve things, but with any change the initial perception is that the change is bad in some way.

Using perceptions to manage: An example of how to transform a perception into improved performance feedback

In today’s article, I take an instance of when a manager feels compelled to use the line “There’s a perception that. . .” as a means to give performance feedback. For example, a manager may intend to “help” the employee by saying, “There’s a perception that you are difficult to work with.” The implied notion is that the perception is the negative impact, and “being difficult to work with” is the behavior that needs to change.

However, this is badly given performance feedback, and there is an alternative!

Citing perceptions as feedback is the reverse order of good performance feedback, so let’s turn it around.

Here are the (compressed) steps for giving performance feedback:

- Start with the context

- Describe the observed behavior

- (Only if it isn’t clear what the impact is) cite the impact of the behavior

- Offer alternate behavior.

Let’s take the example of a manager who attempts to give feedback by saying the following:

“There’s a perception that you’re difficult to work with.”

By leading with the perception, manager reverses the order of feedback and eliminates the other steps. It starts and ends with the so-called impact: The negative perception of being difficult to work with. Aside from the generalization of the employee being difficult to work with, there are no cited behaviors that lead up to the perception. The impact, however ephemeral, is the feedback.

Using perceptions to manage: What does this tell us about the manager’s feedback providing skills?

Today I continue my series of articles on the impact of a manager using perceptions to manage. Frequently, managers start feedback by saying, “There’s a perception that. . .” For example, “There’s a perception that. . . you need to improve your communication skills.” Or “There’s a perception that. . . you are not confident.”

When a manager adds the perception line, it creates all sorts of chaos. Check here, here, here, here and here, for some reasons behind this chaos. But it also give us insight on how performance feedback can be improved by understanding why a manager wants to use the “perception” line in giving feedback.

Here is what we can learn about the actual feedback being provided when the manager breaks out perceptions as the key ingredient to the feedback.

17. The feedback is not specific and not immediate

Using the line, “There’s a perception that” is automatically a modifying clause that takes you one step away from the specificity and immediacy of whatever behavior is being discussed and asked to be modified.

The feedback is by definition not immediate since a time lag is generated: There was a behavior, then there was a perception.

The feedback is by definition not specific, because the discussion is about the perception and not the behavior. The discussion centers around the non-specific perception and distracts away from the specific behavior.

In order for feedback to be effective, it needs to be specific and immediate.

Using perceptions to manage: Are positive perceptions cited?

Today I continue my extended series on managers using perceptions to manage the team. Imagine a manager who starts a performance feedback session with “There’s a perception that. . . you don’t actively participate.” Or “There’s a perception that. . . you’ve fallen behind on your work.”

I believe that these words, “There’s a perception that” need to be removed from a manager’s vocabulary. I provide three reasons here, Three more reasons here, and three more reasons here.

But I have more reasons! Today I examine why positive perceptions are not cited when managers manage perceptions.

10. “There’s a perception that. . .” is rarely used for positive things, underscoring the absurdity of the line

Have you ever noticed that a manager never sits down with an employee and says, “There’s a perception that you deliver on time with high quality and exceptional teamwork”? or “There’s a perception that you bring talents to the group that no one else has.” Or “There’s a perception that you designed and created an infrastructure that increased productivity by 40% and reduced costs by 60%”. Or perhaps a more pedestrian example, “There’s a perception that you’re always on time.”

Hmm. . . as soon as it’s positive things, the “perception” line seems to be unnecessary and weird. . .if the perception of the thing is a the positive thing. Managers who can articulate the positive thing don’t need to add the “There’s a perception that. . .”

11. It twists positive feedback into negative feedback even for positive behaviors and perceptions!

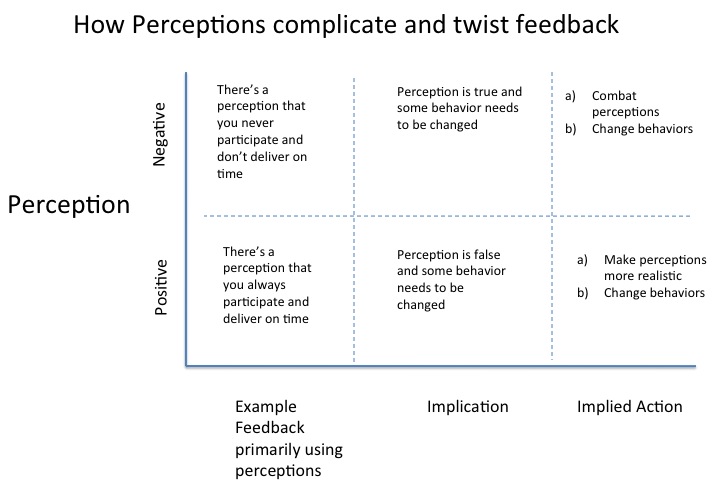

Let’s take a look at the below chart. In it we have an example of a manager giving negative “feedback” and positive “feedback” while inserting the “there’s a perception” line.

Normally, when you give positive feedback on something, it means that you want the employee to keep doing that behavior, or do it with more frequency. But in this chart, you can see that by adding the “there’s a perception” line to the positive feedback, the implication is that something is wrong – that the perception is false in some way and the perception needs to be adjusted to a more realistic perception. (Ironically, when the perception is a negative one, that perception is widely believed to be true.) On top of that, the implication is that the underlying behaviors that created that over-inflated perception also need to be changed so that future perceptions will be the more realistic perception.

So by adding the “there’s a perception” line to a positive behavior, it turns it into a negative perception and a negative behavior. Now the employee has to change both perceptions and the underlying behaviors – on something that is being praised!

In short, it becomes twisted when a positive perception implies that things need to change. Read more

Using perceptions to manage: Three unintended consequences, or, how a manager can create a gossip culture in one easy step

Today I continue my series on managers managing perceptions, and how attempting this creates difficult situations and doesn’t resolve problems. When I say, “Managing perceptions”, I’m thinking of when a manager attempts to use perceptions as the basis for what is being managed, rather than using observed behaviors to manage the team.

Imagine a manager who attempts to give feedback by saying, “There’s a perception that you are easily excitable” or “There’s a perception that you easily get confused.” That’s using perceptions to manage.

In previous articles, I discuss how this deflects from actual performance and creates confusion as to what is real and not real. In today’s article, I discuss some more unintended consequences of a manager relying on perceptions to manage the team – how it creates an instant culture of gossip.

7. Citing perceptions confirms that gossip, innuendo, and back-biting is acceptable and encouraged, if not the default

When a manager says, “There’s a perception that. . .” it confirms that gossip, innuendo, and back-biting is an acceptable and encouraged behavior, both by employees and the manager. By definition, invoking the perception concept is gossip, since it does not rely on any sort of fact or evidence. The only fact that is confirmed is that there is gossip, innuendo and, most likely, back-biting that is occurring. On top of this, gossip and innuendo is now the default mechanism for understanding what is going on with the team. Read more

A second phantom job many employees have: Managing perceptions of others

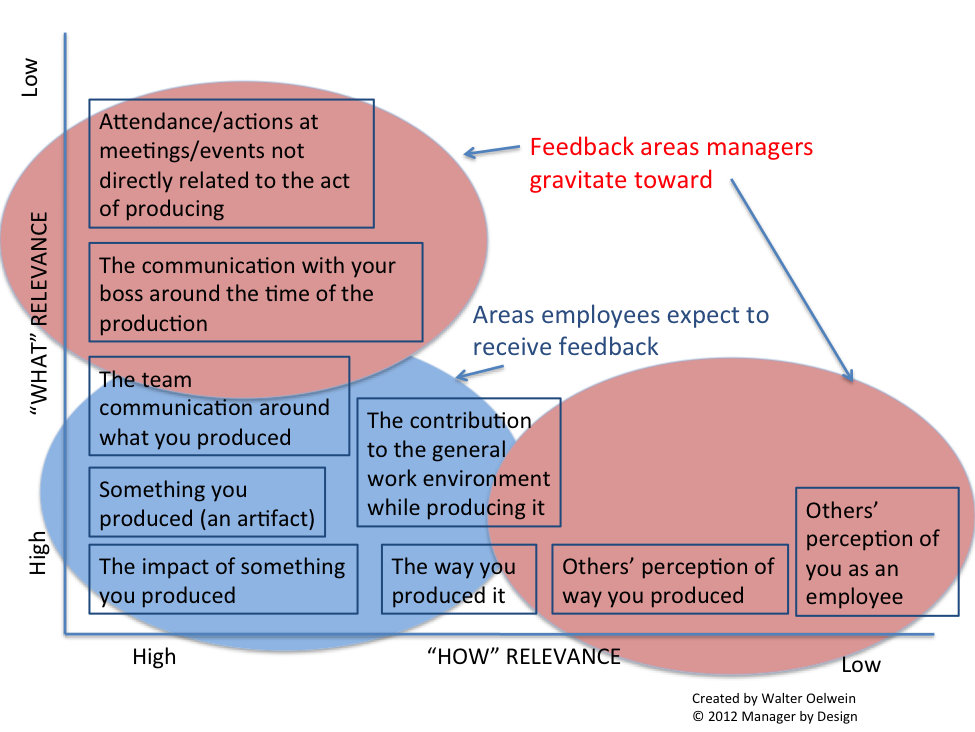

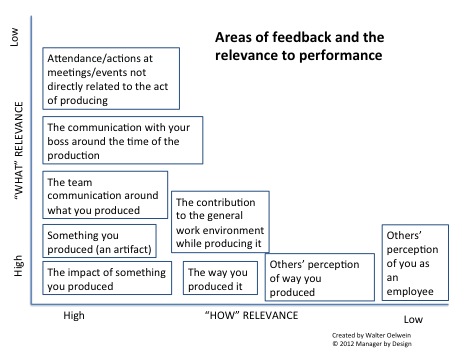

In my previous article, I shared a model to determine the relevance of the performance aspect of performance feedback that many managers give to employees. Here’s the model:

In looking at the upper left corner of this model, many managers create, via the act of giving performance feedback, a second job for the employee: How the employee performs in front of the boss.

So now the employee has two jobs: 1. The job and 2. The job of performing in front of your boss.

The model reveals also in the lower left corner that when a manager gives performance feedback, a third job is often created:

3. The job of managing the perception of others in how you perform your job. Read more

A model to determine if performance feedback is relevant to job performance

In my previous article, I discussed a common mistake managers make: They evaluate the “interactions with the boss” performance, and not the “doing your job performance.” So an employee can go through an entire year and not receive performance feedback on the work he was ostensibly hired to do, but receive lots of performance feedback on how he interacts with his boss.

Given this concept of receiving feedback on the job performance vs. receiving feedback on the “in front of the boss” performance, let’s create a model to help managers get closer to the actual performance of an individual, and where the performance feedback needs to be.

Here is a grid that looks at various elements that employees commonly receive “performance feedback” on. I put these elements into boxes along the “what/how” grid, with the most relevant to job performance being toward the lower left, and the least relevant up and to the right.

In looking at this grid, you can see that what is most relevant is the impact of something produced, with the next most relevant elements being the actual thing you produced, and the way you produced it. Finally, the contribution to the general environment and the communication around the thing produced is the next most relevant element. The closer to the lower left, the closer it is it performance.