A model to determine if performance feedback is relevant to job performance

In my previous article, I discussed a common mistake managers make: They evaluate the “interactions with the boss” performance, and not the “doing your job performance.” So an employee can go through an entire year and not receive performance feedback on the work he was ostensibly hired to do, but receive lots of performance feedback on how he interacts with his boss.

Given this concept of receiving feedback on the job performance vs. receiving feedback on the “in front of the boss” performance, let’s create a model to help managers get closer to the actual performance of an individual, and where the performance feedback needs to be.

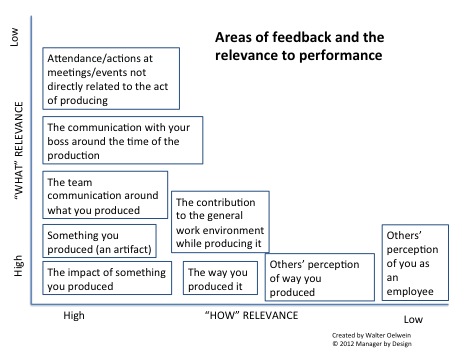

Here is a grid that looks at various elements that employees commonly receive “performance feedback” on. I put these elements into boxes along the “what/how” grid, with the most relevant to job performance being toward the lower left, and the least relevant up and to the right.

In looking at this grid, you can see that what is most relevant is the impact of something produced, with the next most relevant elements being the actual thing you produced, and the way you produced it. Finally, the contribution to the general environment and the communication around the thing produced is the next most relevant element. The closer to the lower left, the closer it is it performance.

Performance feedback must be related to a performance

Have you ever received performance feedback about what you say and do in a 1:1 meeting?

Have you ever received performance feedback about your contributions to a team meeting?

Have you ever received performance feedback about not attending a team event or party?

Were you frustrated about this? I would be. Here’s why:

The performance feedback is about your interactions with your manager and not about what you are doing on the job. This is an all-too-common phenomenon.

If you are getting feedback about items external to your job expectations, but not external to your relationship with your boss, you aren’t receiving performance feedback. You’re receiving feedback on how you interact with your boss. The “performance” that is important is deferred/differed from your job performance, and into a new zone of performance – your “performance in front of your boss.”

OK, so now you have two jobs. 1. Your job and 2. Your “performance in front of your boss.”

Tenets of management design: If you can’t break down a job into its tasks and workflows, find someone who can

Today I discuss a key element to managing well: Knowing what your team members are supposed to do.

This is part of a continuing series that explores the tenets of Management Design, the field this blog pioneers. Management Design is a response to the poorly performing existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident or anointment, rather than by design.

Today’s tenet: If you can’t break down a job into its tasks and workflows, find someone who can.

Many managers are expected to manage a team of people, but really don’t have the clarity as to what the team members are expected to do. Managers often have a sense of what their customers want, and what some examples of things the team produces, or metrics that indicate success (such as sales).

But these are, for the most part, results or indicators of what the team does, not what the team does. The manager should have an understanding of what the component tasks are for the team members’ roles, and when added up, equals the thing that is produced, which then generate the metrics or impressions of success of the team.

Tenets of management design: Doing managerial tasks is what adds up to being a manager

In today’s article, I discuss the meaning of what it means to be a manager. This is part of a continuing series that explores the tenets of Management Design, the field this blog pioneers. Management Design is a response to the poorly performing existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, or that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

Today’s tenet: Doing managerial tasks is what adds up to being a manager.

The current understanding of what it means to be a manager is to receive the designation of “manager.” If someone gets a role as “manager”, they are now a manager. Notice that the new manager does not have to perform any managerial tasks to get this designation. This explains why many managers can “be a manager” without actually doing anything managerial (see my series on manager identity). That manager can perform any number of things that are not managerial (continuing to do the individual contributor work, for example), and still be the manager. That manager can do things that are the exact opposite of good management practices (such as yelling or making generalizations about employees, for example), and still be considered a manager by virtue of being designated the manager.

A common identity of a manager is the ability to rise in the organization – and is this a good thing?

I’ve recently been writing about how the act of becoming a manager is an act that destroys the personal work identity of that new manager. The manager no longer gets to do what they were good at as an individual contributor (IC), and now they are doing something they are new at – and perhaps in an awkward and amateurish way. So the identity of being good at the former job is lost, and the ability to do the new job of management is slow to develop – if ever.

However, there is one aspect the new manager’s identity that is quickly formed via the act of becoming a manager. That is: The ability to “rise” through the ranks.

This is a differentiation that the others individual contributors (IC) in the organization do not have. Only the manager has demonstrated this “skill.” So while the new manager may lose his ability to perform the IC job, is no longer an expert at the IC job, and suffers through suddenly being amateurish at his job, the manager is indisputably good at one thing: Getting promoted into the manager ranks.