An obsession with talent could be a sign of a lack of obsession with the system

Malcolm Gladwell wrote an excellent article called “The Talent Myth”, which appears in his book What the Dog Saw. In this article, he discusses companies that obsess over getting the top talent and the consequences of this. He focuses on Enron, and how it sought obsessively to attract and promote those with the most talent, which, amongst other things, resulted in a high degree of turnover within the company and made it difficult to figure out who actually was the best talent. In the article he asks:

“How do you evaluate someone’s performance in a system where no one is in a job long enough to allow such evaluation? The answer is that you end up doing performance evaluations that aren’t based on performance.” (What the Dog Saw, p. 363)

Does this describe your organization?

I’ve recently written about how many organizations go through a painful, angst-ridden and rhetorically charged process of identifying who the top performers are in an organization. Different managers assert their cases and advance some employees as “high potentials” and others as “needs improvement.”

This effort inures the concept that there is some sort of truth about an individual performer in comparison to her peers, and that this is relationship is static. Or, when it comes to annual reviews, true for at least one more year.

The process of deciding who’s on top and who needs improvement is an ongoing assertion that talent is the most important thing. If you can get more talented people, the more successful you will be. That is the thesis that this activity of ranking employees seems to advance.

But as Malcolm Gladwell’s article shows, this isn’t such a great idea, and it’s a weak thesis at best. There really is no way to judge performance in a highly evolving situation, and the judgment quickly moves from who has the most talent to who appears to have the most talent or who claims to have the most talent. As I showed in my article On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees, such decisions are usually made by tertiary impressions rather than a first hand examination of performance.

It’s a management short cut – the notion that if we have the top people, then everything will just fall into place. But for some reason, this rarely seems to work out.

More reasons the big boss’s feedback on an employee is useless

Perhaps I’m obsessing about this scenario too much, but I just can’t get out of my head the damage that managers of managers cause when they start assessing employees not directly reporting to them. I call this “tagging” an employee.

In a previous post, I describe the moment where a “big boss” (the employee’s manager’s manager) meets with an employee (or even just hears something about an employee or sees a snapshot of the employee’s work) and provides an assessment of the employee. “That employee really knows what she’s doing!” “That employee doesn’t seem to have his head in it.”

The problem? There are many:

–It rates the employee on behaviors not directly related to doing the job, but it’s based on an abstracted conversation about the work or a limited impression of the employee.

–It puts the manager in the middle in a situation where it would seem appropriate to correct the employee, even when it is inappropriate.

I describe what the manager ought to do about this here. But I’m still obsessed with the peculiar angst that this kind of indirect feedback will create in the employee – even when the “feedback” is good. So before I dive into my obsession, my advice to the managers of managers out there: Don’t provide assessments on an employee. Keep it to yourself. If you are really into assessing an employee’s value, you have to do the work of direct observation of work performance.

Now, let’s look at this “feedback” from the employee’s perspective and the damage it causes in an organization:

When a big boss starts trying to identify the top performers and the bottom performers based on their limited interactions, here is a survey of the damage it causes:

Makes employees one-dimensional: The employee immediately transforms from a multi-talented, hard-working, problem-solving contributor to whatever the “tag” is. This is bad even if the tag is good! If the tag is “hard working”, it diminishes the problem-solving, multi-talented part. It also creates a cloud around what the employee does the whole time at work, and instead puts a simplistic view of the employee’s value.

Assumes that the employee is like that all the time: Similarly, if the employee does a particular thing that gets the big boss’s notice, then that is the thing that the employee has to live up to or live down. For example, if the employee does a great presentation, that is what the employee is seen as being good at – the presentation, and the employee is expected to be presenting all the time to have value. There’s no visibility into the teamwork, project management, collaboration, technical insights, or creativity that went into the presentation. Just the presentation. Then if the person is not presenting all the time, then perhaps they are slacking off? That’s what the big boss might think!

What to do when your boss gives feedback on your employee? That’s a tough one, so let’s try to unwind this mess.

Here’s the scenario:

Your employee meets with your boss for a “skip level” meeting. After the meeting, the employee’s boss’s boss (your boss) tells you what a sharp employee you have.

Or, let’s say that your boss tells you that your employee needs to “change his attitude” and “has concerns about your employee.” This is very direct feedback about the employee, and it comes from an excellent authority (your boss), and if you disagree with it, you disagree with your boss.

But this information is entirely suspect. Whether the feedback from the “big boss” is positive or negative, the only thing it reveals is how the employee performed during the meeting with the boss. And unless your employee’s job duty is to meet with your boss, it actually has nothing to do with the expected performance on the job. So if the feedback is negative, do you spend time trying to correct your employee’s behavior during the time the employee meets with the big boss, when it isn’t related to the employee’s job duties?

In addition, the big boss often prides him or herself on the ability to cut through things and come to conclusions quickly, succinctly, and immediately. The big boss will come to a conclusion about the employee based on the data provided in the one-on-one meeting, and will expect this conclusion to be corroborated by you and everyone else.

The big boss, in this process, will put a tag on the employee, whatever it is. Here are some examples of tags:

Up-and-comer

Introverted

Not a go-getter

Whip-smart

Not aware of the issues

Could be a problem

. . .or, the dreaded, ambiguous, “I’m not sure about him.”

What’s worse, since the “tag” originated with the big boss, it will likely stick.

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

Today I want to talk about a management team and how it relates to employees. Imagine the management team. They are in charge of the project of evaluating the performance of their collective employees. In some organizations, they are asked to “stack rank” all employees in an organization, or at least put them in general categories, such as low performer, average performer, high performer, or some variation like, “Needs improvement” at the bottom of the rank to “High Potential” at the top of the rank.

OK, now the management team needs to do the work of ranking the employees. The person facilitating this process is likely to be the manager of the team of managers, or the manager above that. So you have a bunch of managers in a room discussing a large batch of employees’ performance, making arguments about who is a good performer, who is an average performer and who is a low performer. Oftentimes there is a forced curve that requires some people into the “needs improvement” bucket. Oftentimes these discussions have promotion implications and bonus implications. In the examples of companies that have adopted the “fire the lowest 10%” philosophy, it also has firing implications.

Inevitably, the employees know that this kind of thing is happening between the managers. This is a common practice at many large organizations, and a tough one to get right. I’m not really sure it is possible to get right, and here’s why.

In a discussion like this, each manager is armed with some data about the employee. As discussed frequently in this blog, that data about how an employee performed is limited at best, and non-existent at worst.

There are cases where there are specific metrics that are directly comparable across employees, and a certain amount of fairness can be achieved by this measure. This typically occurs with employees at the lower level of an organization, and if you have several employees doing similar or repetitive work that produces comparable metrics. This is decreasingly the case, however, as even – or especially — entry-level positions require more quality-minded, customer-oriented, problem-solving type thinking to achieve high-pressure work goals. So even when there are directly comparable metrics, there are many intangibles that come into play.

So inevitably, it seems that current management design requires that managers get in a room and essentially argue who is the best employee, whether they deserve a raise, and, in many cases, argue that the other employees are less deserving.

Now, what’s tough is that these decisions are way out of the employee’s control – even if they have done amazing work through the year.

Here’s why:

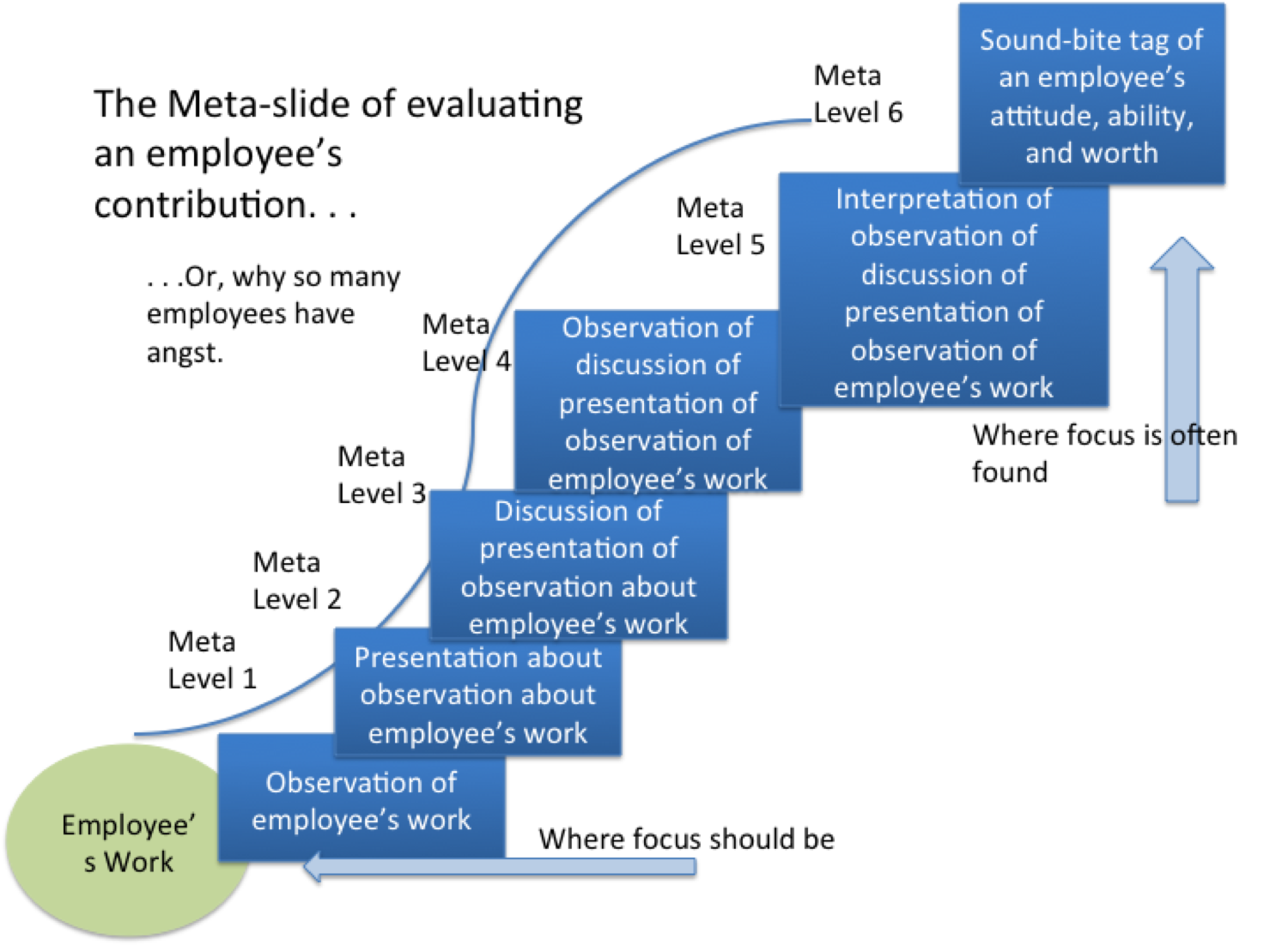

The discussion is inevitably a summary statement of everything an employee has done through the year, and that summary statement cannot possibly be true. In the “stack rank” discussion, a certain amount of meta-analysis of the employee’s performance and worth is required. Here’s what I mean:

Management Design: The “designs” we have now: Send them to training (part 2)

This is the second part of my examination of Management Training Programs as a management design. In the first part of this series, I describe how the impact of a management training class inevitably fades or never even takes hold in the first place. In today’s article, I examine a few forces outside of the training class that have the possibility, if not the likelihood, of creating different or even the exact opposite behaviors from what was covered in management training.

The scenario is this: A new or existing manager attends a management training program. This program can range from a few hours to several days. Then what happens? In many programs, nothing. The manager is expected to go and apply what was learned in training. In others, a mentor might be assigned. While I’m supportive of training and mentoring as a component of management design, current management design tends to be too weak to achieve this goal, often to detrimental effect. See if these conditions apply to your organization:

Is it possible for the manager to do something different (or even the opposite) from was covered in management training class?

Management Design: The “designs” we have now: Send them to training (part 1)

The Manager by Design blog advocates for a new field called Management Design. The idea is that the creation of great and effective Managers in organizations should not occur by accident, but by design. Currently, the creation of great managers falls under diverse, mostly organic methods, which create mixed results at best and disasters at worst. This is the latest of a series that explores the existing designs that create managers in organizations.

Today I discuss a common and consciously-created current design to create managers: The Management Development Training Class.

In this design, the new or existing manager goes to a training class to learn the skills necessary to be a better manager. Awesome! This is very much needed, as there are many mistakes that managers make, and something needs to be done to make sure both new and existing managers don’t make them.

The training classes for teaching management practices can be internal (developed inside the organization), or external (developed and perhaps delivered outside the organization). They can take place over the course of a few hours, or perhaps over several days. Some management development programs very consciously take place over a series of months and have regular check-ins on how it is going with the new manager. More sophisticated management development programs will have mentor programs.

I’ve very supportive of any effort to improve the quality of management skills, and the management development class is a great way to start, and should be a cornerstone of any management design. So as a start, let’s give cheers to the management development programs out there!

But how does a management training program stack up as design? Read more

Management Design: The designs we have now – Promote the one who asks for it

The Manager by Designsm blog advocates for a new field called Management Design. The idea is that the creation of great and effective Managers in organizations should not occur by accident, but by design. Currently, the creation of great managers falls under diverse, mostly organic methods, which create mixed results at best and poor results at worse. This is the latest of a series that explores the existing designs that create managers in organizations.

Today’s design: Promote the one who asks to become the manager.

In this “design”, the person who asks for the promotion to manager is the one who gets it. You know the scenario: A member of the team consistently asks for the promotion to management in their one-on-one discussions; a member of the team states that they expect to be director by the end of the year; a member of the team self-identifies as the one with the most leadership potential.

Using this “design” to generate managers, the hiring manager skews toward the one who has the most moxie, drive, ambition, confidence, and apparent leadership ability. After all, let’s look at the opposite. Those who don’t ask for the promotion apparently have less moxie, less drive, less ambition, less confidence and do not appear to have leadership ability. Case closed—hire the one who wants it the most – the one who asks for it.

But what are the down sides of this design? Plenty. Read more

The Cost of Low Quality Management

The Manager by Design Blog provides helpful tips for how managers can improve their people management skills and team management skills. The blog also advocates for the new field of “Management Design,” where managers are created systematically rather than placed into an arena where they have to perform without systematic help.

But is this really needed? Aren’t managers performing well already? Do managers need to improve how they perform?

Here’s a survey of some recent articles that discuss this very topic. Warning: It may not be pretty.

Poor Managers may cause illness and heart attacks: According to a recent study in Sweden, poor management increases both the amount of sick leave and creates a greater risk of heart attack. Conversely, those with good managers had less sick time. More info can be found here.

Poor Managers hurt productivity and profitability: In 2004, an ongoing Gallup survey that indicates poorly managed workgroups are an average of 50% less productive and 44% less profitable than their well-managed counterparts. (Cited here and here ) and in the May 1, 2005 edition of HR Focus.

Management Design: The “designs” we have now: Make the loudest person the manager

The Manager by Design blog advocates for a new field called Management Design. The idea is that the creation of great and effective Managers in organizations should not occur by accident, but by design. Currently, the creation of great managers falls under diverse, mostly organic methods, which create mixed results at best. This is the latest of a series that explores the existing designs that create managers in organizations. Today’s design: Make the loudest person the manager.

“Loud” in this context can mean many different things:

–The person with the most booming voice

–The person who is quick to raise his or her voice

–The person who speaks up the most

–The person who makes the most dramatic flourishes

–The person who enjoys public speaking the most

–The person who shouts others down

The main benefit of this “design” is that you get ready-built confidence and appearance of authority. It also is intuitive that the person who is loudest seems to have the most “natural leadership ability” and can “command the room” the best. This is great design if this is what your conception of what a manager is – someone who stands before others, commanding and billowing orders. It’s a common notion that has rung true through the years. The opposite of this seems very hazardous: A “technocrat” who is “meek” and doesn’t know how to lead. Thus it is a popular design: Promote the loudest and the others will follow.

But there are some problems with this design. Read more

Management Design: The “designs” we have now: Recruit someone from a successful comparable organization

The Manager by Designsm blog advocates for a new field called Management Design. The idea is that the creation of great and effective people managers in organizations should not occur by accident, but by design. Currently, the creation of great managers falls under diverse, mostly organic methods, which create mixed results at best and disasters at worst. This is the latest of a series that explores the existing designs that create managers in organizations. Today’s design: Hire someone from a successful comparable organization, such as a competitor. Read more