Management Design: Structure and Feedback in a focused area of leadership

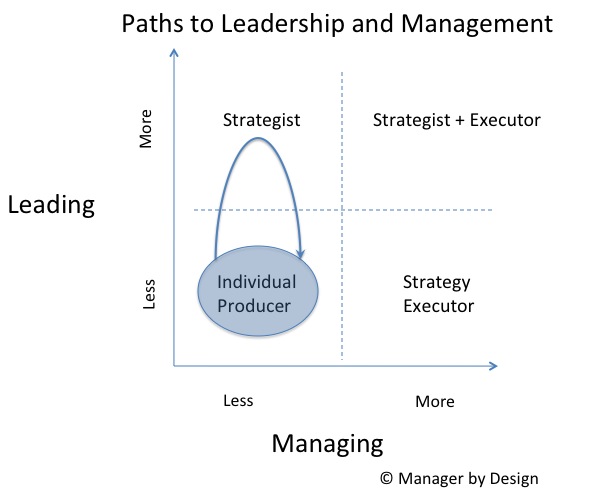

In my previous article, I propose a design that allows for a more systemic and purposeful way of developing managers and leaders. The basic idea is to provide leadership opportunities (setting strategy) and management opportunities (executing the strategy) without conflating both.

Here’s how it looks in the Manager by Designsm leadership and management model:

Under this model, the design is to identify people who are good at strategy, identify people who are good at strategy execution (management) and make sure that they are good at either strategy or strategy execution.

The same individual can try out both paths – if that individual is considered some sort of amazing performer – but this design is intended to find lots of people who are good at leadership and management, not just that magical super-performer as the current designs seem to be skewered toward.

Using perceptions to manage: An example of how to transform a perception into improved performance feedback

In today’s article, I take an instance of when a manager feels compelled to use the line “There’s a perception that. . .” as a means to give performance feedback. For example, a manager may intend to “help” the employee by saying, “There’s a perception that you are difficult to work with.” The implied notion is that the perception is the negative impact, and “being difficult to work with” is the behavior that needs to change.

However, this is badly given performance feedback, and there is an alternative!

Citing perceptions as feedback is the reverse order of good performance feedback, so let’s turn it around.

Here are the (compressed) steps for giving performance feedback:

- Start with the context

- Describe the observed behavior

- (Only if it isn’t clear what the impact is) cite the impact of the behavior

- Offer alternate behavior.

Let’s take the example of a manager who attempts to give feedback by saying the following:

“There’s a perception that you’re difficult to work with.”

By leading with the perception, manager reverses the order of feedback and eliminates the other steps. It starts and ends with the so-called impact: The negative perception of being difficult to work with. Aside from the generalization of the employee being difficult to work with, there are no cited behaviors that lead up to the perception. The impact, however ephemeral, is the feedback.

Using perceptions to manage: What does this tell us about the manager’s feedback providing skills?

Today I continue my series of articles on the impact of a manager using perceptions to manage. Frequently, managers start feedback by saying, “There’s a perception that. . .” For example, “There’s a perception that. . . you need to improve your communication skills.” Or “There’s a perception that. . . you are not confident.”

When a manager adds the perception line, it creates all sorts of chaos. Check here, here, here, here and here, for some reasons behind this chaos. But it also give us insight on how performance feedback can be improved by understanding why a manager wants to use the “perception” line in giving feedback.

Here is what we can learn about the actual feedback being provided when the manager breaks out perceptions as the key ingredient to the feedback.

17. The feedback is not specific and not immediate

Using the line, “There’s a perception that” is automatically a modifying clause that takes you one step away from the specificity and immediacy of whatever behavior is being discussed and asked to be modified.

The feedback is by definition not immediate since a time lag is generated: There was a behavior, then there was a perception.

The feedback is by definition not specific, because the discussion is about the perception and not the behavior. The discussion centers around the non-specific perception and distracts away from the specific behavior.

In order for feedback to be effective, it needs to be specific and immediate.

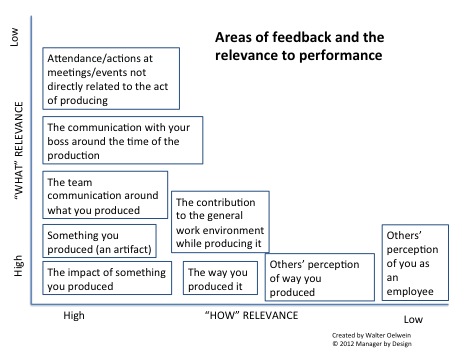

A model to determine if performance feedback is relevant to job performance

In my previous article, I discussed a common mistake managers make: They evaluate the “interactions with the boss” performance, and not the “doing your job performance.” So an employee can go through an entire year and not receive performance feedback on the work he was ostensibly hired to do, but receive lots of performance feedback on how he interacts with his boss.

Given this concept of receiving feedback on the job performance vs. receiving feedback on the “in front of the boss” performance, let’s create a model to help managers get closer to the actual performance of an individual, and where the performance feedback needs to be.

Here is a grid that looks at various elements that employees commonly receive “performance feedback” on. I put these elements into boxes along the “what/how” grid, with the most relevant to job performance being toward the lower left, and the least relevant up and to the right.

In looking at this grid, you can see that what is most relevant is the impact of something produced, with the next most relevant elements being the actual thing you produced, and the way you produced it. Finally, the contribution to the general environment and the communication around the thing produced is the next most relevant element. The closer to the lower left, the closer it is it performance.

Performance feedback must be related to a performance

Have you ever received performance feedback about what you say and do in a 1:1 meeting?

Have you ever received performance feedback about your contributions to a team meeting?

Have you ever received performance feedback about not attending a team event or party?

Were you frustrated about this? I would be. Here’s why:

The performance feedback is about your interactions with your manager and not about what you are doing on the job. This is an all-too-common phenomenon.

If you are getting feedback about items external to your job expectations, but not external to your relationship with your boss, you aren’t receiving performance feedback. You’re receiving feedback on how you interact with your boss. The “performance” that is important is deferred/differed from your job performance, and into a new zone of performance – your “performance in front of your boss.”

OK, so now you have two jobs. 1. Your job and 2. Your “performance in front of your boss.”

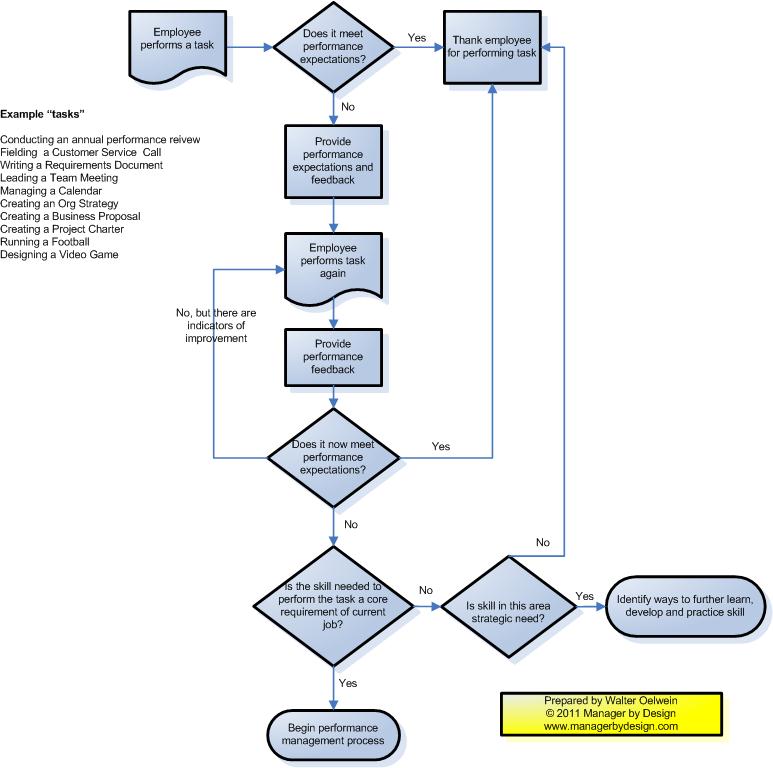

A Performance Feedback/Performance Management Flowchart

The Manager by Designsm blog seeks to create better managers by design. Here’s a great tool that outlines a simple flowchart of when a manager should provide performance feedback, and when the performance management process should occur. It can be used in many contexts, and provides a simple outline of what a manger’s role is in providing feedback, and how this fits with the performance management process (click for a larger image).

You’ll see that Performance Feedback starts at the task level, not the person level. You want to know what the task is, and make sure the individual gets feedback on how well he or she is performing the task. It also requires the manager to know what acceptable performance looks like. If not, then the manager is in a complex feedback situation, and both the manager and the employee agree to strategize on how to do the task differently, since it isn’t defined yet.

You’ll also notice that there is a lot of activity prior to the performance management process, which is actually a more formal version of this same flowchart. Managers need to perform this informal version first.

Let me know what you think. Do you your managers follow this flow chart? Do they skip steps? Do they add steps?

Related articles:

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

How to have a feedback conversation with an employee when the situation is complex

A tool to analyze the greater forces driving your employee’s performance

When an employee does something wrong, it’s not always about the person. It’s about the system, too.

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

What inputs should a manager provide performance feedback on?

When to provide performance feedback using direct observation: Practice sessions

When to provide performance feedback using direct observation: On the job

Performance Feedback is about next time

Here’s a scenario: Jim reacts badly to a new change in the organization. He starts telling all of his co-workers how much he doesn’t like the change, and discusses ways to undermine or avoid the change. This causes increased doubt in the change, and even causes confusion as to whether the change is actually going to happen.

Jim manager has the option of either addressing or ignoring Jim’s reaction. If the manager addresses it, this would be a performance feedback conversation.

However, many managers avoid the performance feedback conversation. One reason for this is the manager may believe that Jim’s behavior on the job is deeply embedded in the employee’s personality, and the employee’s actions are innate to their very being. So a basic thesis emerges that “Jim is just like that.” There is the belief that Jim just won’t change. So no performance feedback conversation is necessary.

But this is an untested thesis. Jim did react badly to the news, but does this mean that he has to react the same way next time? The answer is—you don’t know until you have the performance feedback conversation.

If you don’t have the performance feedback conversation, the Jim will definitely behave in the exact same way should a similar set of circumstances occur. His behavior was “negatively reinforced,” meaning that he received no information that his behavior was incorrect and he received no adverse reaction from his manager. In fact, his behavior may have also been “positively reinforced” when the other employees start agreeing with his arguments about how he doesn’t like the change. The manager, by being silent, is letting the other forces of behavior determine Jim’s behavior in the workplace.

So the basic thesis that Jim “always is like that” only is true if he never receives coaching or feedback on what he should do instead. And when the manager does not step in, then for sure this thesis will be proven correct.

The Art of Providing Feedback: Banish the use of “always”

Here’s a tip for managers: Banish the word “always” from your vocabulary.

The Manager by Design blog frequently writes about how to give performance feedback. Performance feedback is an important skill for any manager, as it is one of the quickest ways to improve performance of individuals on your team.

One particularly useless word in the art of performance feedback is the word “always.” Here are some examples of where a manager mistakenly uses “always” in performance feedback:

You’re always late

You always make bad decisions

You always come up short

These are examples of bad performance feedback, since they are not behavior-based, but the word that makes these examples particularly bad is the word “always.” That’s because “always” implies that the employee’s performance is eternal and permanent. And that undermines the whole point of performance feedback, which is to change the way your employees are performing, and have them do something better instead.

Let’s start by removing the word always from the three examples above:

You’re late

You made a bad decision

You came up short

OK, these are still pretty bad, but at least this feedback didn’t put an eternal and permanent brand on the employee as “always late,” “always bad at making decisions,” and “always underperforming.” At least without the word “always”, the feedback is isolated to the once incident, making it possible for the feedback to be more specific and immediate.

Removing the word “always” allows you to focus on the particular event you are giving feedback on, and not make a generalization about the person’s permanent character.

Removing the word “always” allows you to support the thesis about “late” “bad decisions” and “coming up short” with more details. By discussing the details, you at least have entry to discussion as to why this happened, and identify the forces that went into the performance.

Removing the word “always” implies that this bad event can be turned around and the next time the performance can be improved.

When you use the word “always” in a feedback conversation, it implies that there is a permanence to the employee behavior the manager is ostensibly trying to correct. “Always” makes the performance feedback conversation useless, because instead of trying to get the employee to do something differently next time (be on time, make a good decision, meet the goal), it instead sounds like a relegation or banishment to permanent underperformance that the employee can never get out of.

That’s not good for either the manager or the employee, unless you want a chronically underperforming team that hates the manager.

Finally, by saying someone is “always late” or “always makes poor decisions”, it is inherently incorrect. If that employee can find one time he was on time, or one time she made a correct decision, then the manager is proven wrong. Not a good move if you want to be able to lead a team.

So to all of the managers out there – banish the word “always” from your vocabulary.

Have you ever been told that you “always” do something? What was that like?

Related articles:

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

An example of giving specific and immediate feedback and a frightening look into the alternatives

Examples of when to offer thanks and when to offer praise

What inputs should a manager provide performance feedback on?

Getting started on a performance log – stick with the praise

An example of how to use a log to track performance of an employee

Providing corrective feedback: Trend toward tendencies instead of absolutes

Behavior-based language primer for managers: How to tell if you are using behavior-based language

Behavior-based language primer for managers: Avoid using value judgments

Behavior-based language primer for managers: Stop using generalizations