Strive toward strategic placement of employees based on organizational need

In my previous post, I discussed how it takes a lot to compare and stack rank employees, and really the best you can do is to come up with some limited scenarios where you compare similar jobs, with clear rules, consistent evaluators and transparency. With that done, you now have determined the winner in a limited context in a given time frame. So it doesn’t really tell you who is the “best”, but who was the best in that context. If that context comes up a lot, then you can get trends and be more predictive, such as the case in answering “who is the best athlete,” but still leaves a lot open for debate. In the contemporary workplace, these conditions happen less and less.

In the contemporary workplace, employees are asked to adapt to constantly shifting situations, new technologies, new projects, and new skill sets. Instead of who is the “best” at something, it is the who is the “best” at adapting to new situations, which can go in many different directions. You need people who are great in different facets of the work, and who can adapt and improve and strive toward meeting the organizational goals. This makes it very unlikely that you can have some sort of conclusion who is the “best” and who is “on top”, since there is a diversity of skill sets needed to achieve these goals, and they are often shifting.

So instead of “stack ranking” employees, which implies that one employee is inherently better than another (and makes a not-so-subtle argument that it is forever that way), managers need to strategically place employees in roles and projects based on what the managers and employees assess they are good at and their ability to execute. It’s less about who’s the best, and more about what is the best placement to get the work done.

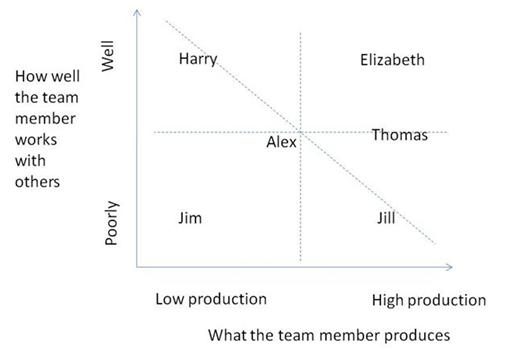

Let’s take a look at the What/How grid to be as a way to be more strategic with a team’s strengths. This grid shows an analysis by a manager of a fictional team, based on “what” the team member produces and “how” they work with others. Other analyses could be performed based on your organizational needs.

In this grid, the manager has assessed that Elizabeth and Thomas as skilled in both productivity and ability to work with others. But the manager also has Harry who seems to get along with lots of people, but doesn’t produce much, and Jill who seems to work really hard but isn’t as focused on relationships. So now the manager, instead of saying, “Elizabeth and Thomas are my top performers”, the manager should say, “What can I do with this group to get the most out of my team?”

I’d put Harry in a role that requires relationships to be forged. I’d make sure I’d give Harry some expectations for what we are looking to get out of those relationships (new leads? sales? higher customer satisfaction? socializing a new program across groups?) and rate him against these expectations. I’d put Jill in a role that is not customer-facing but requires a lot of work output where relationships are less crucial for success, and rate her against what she produces (and diminishing the importance of “how” she produces). Ideally, this most likely feeds to Harry information that makes him better. If I need more customer-facing work and relationship building, I’d put Elizabeth on that, and if I need more work output, I’d put Thomas and Elizabeth at that.

Elizabeth and Thomas are more flexible, which obviously has value, but if the value of customer relationship building is super-important for the team, then perhaps Harry is more valuable than Thomas for now. It isn’t a permanent thing, but a thing that is based on the context of the team’s needs, and not on the context of the employees inherent abilities.

With Alex, I would try to figure out where Alex is most likely to be needed in the near future, and work on giving performance feedback and coaching in the direction where your team is likely to need it. Perhaps Alex can be a back-up to Harry in the follow-up with customers.

With Jim, he rates lowly in two dimensions, which looks like a net-negative to the team, so I would look at the performance management process for him, because it doesn’t look like he’s helping the team at all, and unless he improves (which is entirely possible with the performance management process) there is likely someone else out there who could do his job better.

So instead of saying, “Elizabeth and Thomas” are the most important employees, the manager should first focus on trying to maximize where all employees can most help the team to achieve its goals. This treats all employees as valuable, and is likelier to achieve overall team performance.

This is where the management energy should be spent first and foremost. The shifting dynamics of the team context should be the greater concern, not the ranking of individual employees against one another, since you need the entire team to perform to be successful.

Also note that once placed on this grid, the people are not permanently located there. Any one of them can shift around based on changing circumstances, work stresses and pressures, and individual development.

In this article, I use a very simple “What/How” grid to identify the strengths of the team and to assist with illustrating how a manager can use this simple tool. Another common method is to use the Strength Finder tool from the book Now, Discover Your Strengths, which has many more dimensions and areas of insights and one I would highly recommend any manager do to identify the areas of strengths on the team and then make strategic decisions accordingly.

How much energy does your management team spend in strategically utilizing employee strengths? How does this compare to the amount of time ranking employees?

Related Articles:

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

An obsession with talent could be a sign of a lack of obsession with the system

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

How to use the What-How grid to build team strength, strategy and performance

If you really want to evaluate performance across individuals, here are some things that need to be in place

In my previous article, I discussed how many organizations spend time identifying who the top performers and stack ranking employees, to the detriment of assessing other areas that drive performance. Management teams obsess on determining the best performers are. Once done, this implies you now have what it takes to get ahead in business. It’s an annual rite. Despite this process causing lots of angst, the appearance of accuracy in the face of tertiary impressions, and the general lack of results and perhaps damage it causes, this activity continues to have a high priority for many organizations.

OK, so if you really want to do it – you really want to compare employees — here are some things that have to be in place if you don’t want to cause so much damage and angst in the process:

1. You can compare people only across very similar jobs

Many organizations attempt to compare people across the organization, in kind of similar jobs, and under different managers. Then they try to assess the value of the various outputs of the jobs that had different inputs and outputs. If there were different projects and different pressures, different customers and different challenges, then it will be difficult to say who is the better performer.

An obsession with talent could be a sign of a lack of obsession with the system

Malcolm Gladwell wrote an excellent article called “The Talent Myth”, which appears in his book What the Dog Saw. In this article, he discusses companies that obsess over getting the top talent and the consequences of this. He focuses on Enron, and how it sought obsessively to attract and promote those with the most talent, which, amongst other things, resulted in a high degree of turnover within the company and made it difficult to figure out who actually was the best talent. In the article he asks:

“How do you evaluate someone’s performance in a system where no one is in a job long enough to allow such evaluation? The answer is that you end up doing performance evaluations that aren’t based on performance.” (What the Dog Saw, p. 363)

Does this describe your organization?

I’ve recently written about how many organizations go through a painful, angst-ridden and rhetorically charged process of identifying who the top performers are in an organization. Different managers assert their cases and advance some employees as “high potentials” and others as “needs improvement.”

This effort inures the concept that there is some sort of truth about an individual performer in comparison to her peers, and that this is relationship is static. Or, when it comes to annual reviews, true for at least one more year.

The process of deciding who’s on top and who needs improvement is an ongoing assertion that talent is the most important thing. If you can get more talented people, the more successful you will be. That is the thesis that this activity of ranking employees seems to advance.

But as Malcolm Gladwell’s article shows, this isn’t such a great idea, and it’s a weak thesis at best. There really is no way to judge performance in a highly evolving situation, and the judgment quickly moves from who has the most talent to who appears to have the most talent or who claims to have the most talent. As I showed in my article On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees, such decisions are usually made by tertiary impressions rather than a first hand examination of performance.

It’s a management short cut – the notion that if we have the top people, then everything will just fall into place. But for some reason, this rarely seems to work out.

Tenets of Management Design: Drive towards understanding reality and away from relying on perceptions

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field I’m pioneering, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the bad existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, and that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

Today’s tenet of Management Design: Encourage reality over perception

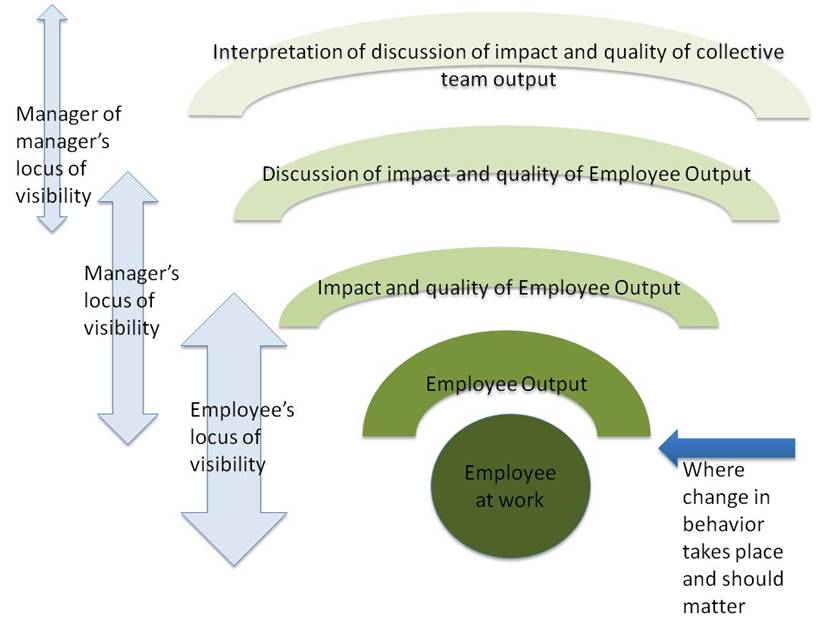

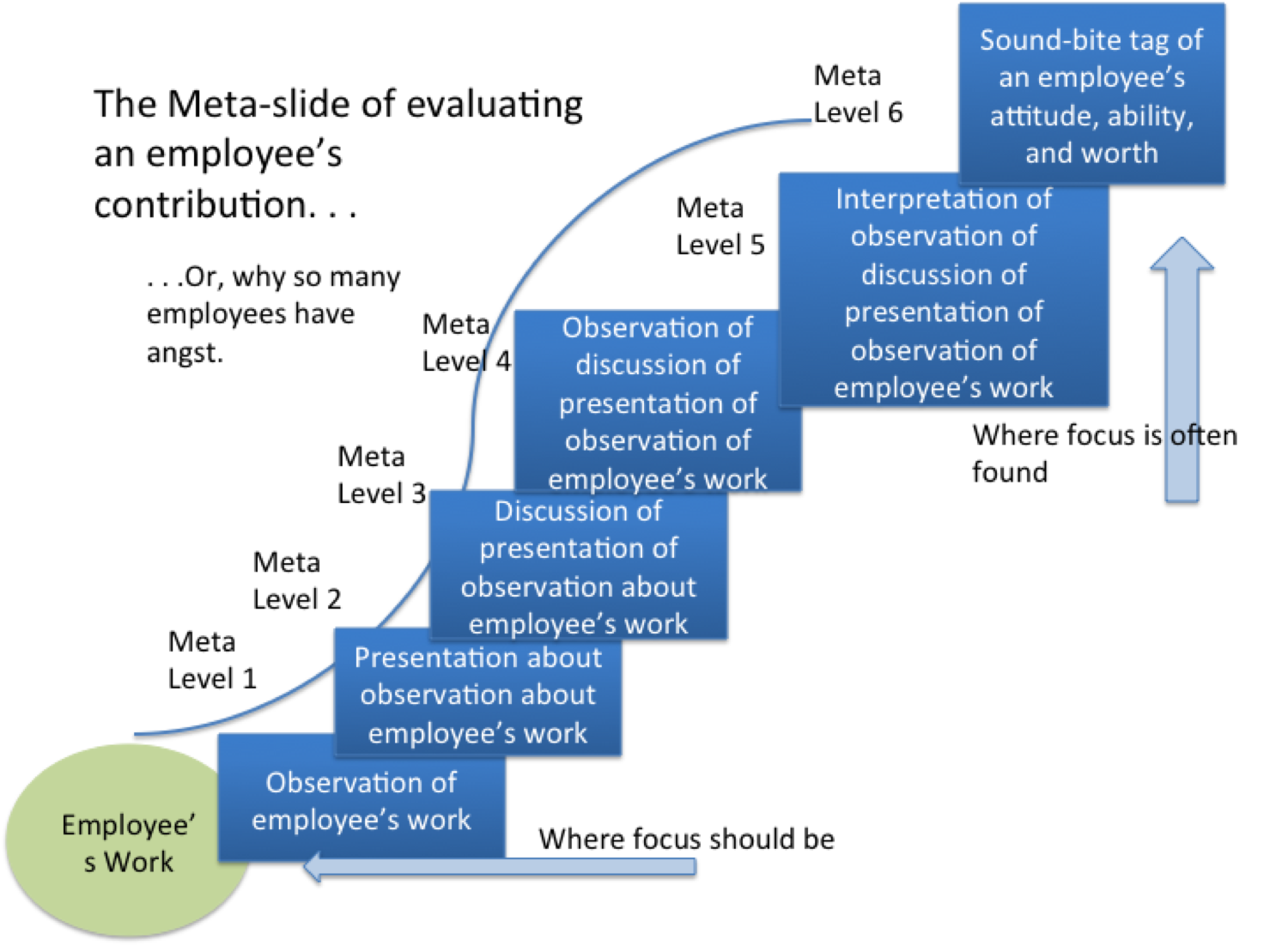

In a previous post, I describe a common situation where employees are evaluated, spliced, diced and put into categories to determine if they need improvement, are high performers, or are in that special purgatory of the middle. The problem with this process is that it requires decisions based on perceptions or, worse, perceptions of perceptions, or perceptions of perceptions of perceptions. This is shown in the “meta slide” of evaluating an employee’s contribution.

This is bad management design. In such a design, managers and managers of managers are charged with the role of doing (what I call) phantom managing — ranking employees — based on argument, rhetoric and perception. Typically, each manager is allowed to bring in their own methods for advocating (or denouncing) their employees, and argues accordingly. This is in the spirit of creating a truth about the employee: Where they fit in the “stack rank,” whether they are “needs improvement” or whether they are “high potential”. The design is, in effect, to create that impression, to create that tag and, for all intents and purposes, institutionalize the worth of the employee as either low, medium or high based on a team of managers’ rhetoric.

Here are some outcomes of this that make this bad, degenerative management design:

- This kind of situation institutionalizes perceptions as the dominant formula for evaluating and tagging employees

- This places an emphasis on evaluation of employees as more important than working with employees to perform at an acceptable level.

- This puts the onus away from the manager and assumes the employee is solely responsible for success in a role

These three outcomes place at a premium the perception of an employee (and what the employee and manager do to manage perceptions), rather than place the focus and emphasis on the reality of the employee’s work output and behaviors.

So instead of focusing on the perceptions, let’s focus on some realities of employee performance:

First, the reality is that no employee can possibly be permanently categorized as low, medium or high. Things are too dynamic – in one situation an employee is great, and in another situation an employee is terrible. Too many times we have observed employees do badly in one context and do great in another (see my article about how to evaluate the system as a part of performance feedback). Does that make the employee good or bad? It’s neither. Putting a tag that risks being a permanent tag creates an unnecessary perceptual problem about the quality of the employee. In addition, that tag, with its trace perception, is likely to carry over year over year.

Next, the reality is that a manager’s role is to do what it takes to make sure the team performs as at high of a level as possible, using the available components of the team, tools, processes and work environment. This evaluative process of tagging employees in one category or another in effect removes that burden from the manager, and creates the perception that the employee capability is the number one factor of team (and manager’s) success, and the rest is out of the manager’s hands. The manager can say, “Well, I have two low performers on my team, thus we couldn’t get it done.” The manager’s real job is not to put those low performers in the low performance bucket, but to figure out how those low performers can contribute to the team to make the team effective. If those low performers are that bad, are a terrible fit, and shouldn’t even be on the team, there is the option of performance managing the low performer. Instead, too many managers wait until the end of the year, exact their revenge on the low performers by saying, “Well, they are low performers!” And sure enough, that low performer appears the following year as a low performer. The manager’s role? Declaring them as low performers.

Third, the reality is that the manager has a huge impact on the individual contributor’s performance, perhaps as much as the individual contributor has on his performance. The manager who sets up expectations well, who assures that there are processes that drive a consistent strategy, who discourages drama and who encourages teamwork will make any set of employees better. These are managers who can turn a team of average performers into a team of star performers (who then get tagged as “high potential” – until those high potentials go into a broken system, then lo and behold they become low performers). Obviously the individual contributors need to bring their “A” game to make a truly high performing team, but with current management design, there is an assumption that every team needs to be filled entirely with Michael Jordans and Zinedine Zidanes to be successful. Simply not the case, as even Messrs. Jordan and Zidane, with all of their success, never had such teams.

Drive the focus toward the reality of an employee’s output

So instead of engaging in meta-perceptual conversations about the relative worth of each employee, good management design should discourage structures that solidify perceptions, and push the manager to the reality of creating as strong a team as possible, focusing on the behaviors of each team member, and getting as close as possible to the reality of the team performance.

The dark green circle is the closest we can get to understanding reality. In good management design, the focus should be that managers think and deal with the employee at work, and try to get the behaviors to the maximum effectives, both as an individual and as a team. The manager still has a few degrees of separation from direct understanding of the reality of the employee’s work, but instead of encouraging moving further away from it, good management design should encourage getting closer to it.

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

Today I want to talk about a management team and how it relates to employees. Imagine the management team. They are in charge of the project of evaluating the performance of their collective employees. In some organizations, they are asked to “stack rank” all employees in an organization, or at least put them in general categories, such as low performer, average performer, high performer, or some variation like, “Needs improvement” at the bottom of the rank to “High Potential” at the top of the rank.

OK, now the management team needs to do the work of ranking the employees. The person facilitating this process is likely to be the manager of the team of managers, or the manager above that. So you have a bunch of managers in a room discussing a large batch of employees’ performance, making arguments about who is a good performer, who is an average performer and who is a low performer. Oftentimes there is a forced curve that requires some people into the “needs improvement” bucket. Oftentimes these discussions have promotion implications and bonus implications. In the examples of companies that have adopted the “fire the lowest 10%” philosophy, it also has firing implications.

Inevitably, the employees know that this kind of thing is happening between the managers. This is a common practice at many large organizations, and a tough one to get right. I’m not really sure it is possible to get right, and here’s why.

In a discussion like this, each manager is armed with some data about the employee. As discussed frequently in this blog, that data about how an employee performed is limited at best, and non-existent at worst.

There are cases where there are specific metrics that are directly comparable across employees, and a certain amount of fairness can be achieved by this measure. This typically occurs with employees at the lower level of an organization, and if you have several employees doing similar or repetitive work that produces comparable metrics. This is decreasingly the case, however, as even – or especially — entry-level positions require more quality-minded, customer-oriented, problem-solving type thinking to achieve high-pressure work goals. So even when there are directly comparable metrics, there are many intangibles that come into play.

So inevitably, it seems that current management design requires that managers get in a room and essentially argue who is the best employee, whether they deserve a raise, and, in many cases, argue that the other employees are less deserving.

Now, what’s tough is that these decisions are way out of the employee’s control – even if they have done amazing work through the year.

Here’s why:

The discussion is inevitably a summary statement of everything an employee has done through the year, and that summary statement cannot possibly be true. In the “stack rank” discussion, a certain amount of meta-analysis of the employee’s performance and worth is required. Here’s what I mean: