Tenets of Management Design: The manager can do a lot to improve “flow”

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s 1990 book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience popularized the concept of “flow” and its importance. So let’s talk about a manager and “flow”. Managers can do a lot to improve flow, and good managementdesign,benefits from being highly focused on encouraging “flow” in the workplace. The more your employees have flow, the more likely they are to produce some pretty amazing stuff. So shouldn’t your management design be focused on improving the “flow” of the employees?

That means fewer disruptions, enabling longer stretches of greater focus. Here are some ideas for managers to improve flow:

The manager can start by not being a distraction. How many times have we had a manager who interrupts our work with both minor questions or new requests for work? With the advent of email, chat, texts, and any other communication mediums including actually stopping by, perhaps the worst offenders are managers who are in the habit of interruptingtheir employees. So good management design would encourage managers not to interrupt employees who are likely to be closer to “flow state.” If the employee seems to be in deep concentration, this is definitely the sign that the employee is not available to be interrupted. If the employee is not responding to emails, this is a sign that the employee is in a focused activity. The manager should have predictable times when they interact with their employees.

Tenets of management design: If you can’t break down a job into its tasks and workflows, find someone who can

Today I discuss a key element to managing well: Knowing what your team members are supposed to do.

This is part of a continuing series that explores the tenets of Management Design, the field this blog pioneers. Management Design is a response to the poorly performing existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident or anointment, rather than by design.

Today’s tenet: If you can’t break down a job into its tasks and workflows, find someone who can.

Many managers are expected to manage a team of people, but really don’t have the clarity as to what the team members are expected to do. Managers often have a sense of what their customers want, and what some examples of things the team produces, or metrics that indicate success (such as sales).

But these are, for the most part, results or indicators of what the team does, not what the team does. The manager should have an understanding of what the component tasks are for the team members’ roles, and when added up, equals the thing that is produced, which then generate the metrics or impressions of success of the team.

Tenets of management design: Doing managerial tasks is what adds up to being a manager

In today’s article, I discuss the meaning of what it means to be a manager. This is part of a continuing series that explores the tenets of Management Design, the field this blog pioneers. Management Design is a response to the poorly performing existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, or that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

Today’s tenet: Doing managerial tasks is what adds up to being a manager.

The current understanding of what it means to be a manager is to receive the designation of “manager.” If someone gets a role as “manager”, they are now a manager. Notice that the new manager does not have to perform any managerial tasks to get this designation. This explains why many managers can “be a manager” without actually doing anything managerial (see my series on manager identity). That manager can perform any number of things that are not managerial (continuing to do the individual contributor work, for example), and still be the manager. That manager can do things that are the exact opposite of good management practices (such as yelling or making generalizations about employees, for example), and still be considered a manager by virtue of being designated the manager.

Tenet of management design: If you don’t have a system, it’s probably being done over email

Managers seem to have a lot of email to work through. Especially managers in office environments. Lots and lots of emails. Managers are always checking emails, responding to emails, catching up on email. Why?

It’s probably because there isn’t a system for whatever is trying to be accomplished via email. Some sample tasks that managers perform via email:

1. Providing team expectations

2. Task direction

3. Problem solving

4. Performance feedback

5. Brainstorming

6. Addressing escalated issues

7. Developing and reviewing work output (documents) of the team

8. Unblocking issues

9. Getting buy-in from partners

10. Answering knowledge questions

11. Coordinating team members to work with one another

12. Giving and getting status updates

13. Promoting the team performance

14. Discussing hiring decisions

15. Doing budgeting

16. Organizing a meeting

17. Reviewing business/team insights

18. Determining the agenda of the meeting

19. Giving follow up after the meeting

I know that I’m missing dozens of other tasks that managers perform, but this sample gives a feel for how integrated email has become in the experience of being a manager (or any employee in an office).

So the question should be – is email the best system to perform these and other tasks? In absence of a system, in many cases email is preferable. But could there be better tools for doing the above things?

Email is a robust and powerful tool for communication. But I fear that its power has held back the development of improved manager capability. Because email exists as a ready means to communicate with your team, your team’s partners and customers and your boss, efforts to improve upon these have rarely been made.

Email is an interesting tool in that each time it is used it re-invents the process for getting the task done. Just as quickly as a process is established over email, that process breaks down (or fades away) as soon as the next issue or task emerges, which is all the time. The time constraints and quality criteria are usually embedded in the email communication (if at all), and generally have no enforcement. Accountability and tracking of who contributed in what way is also difficult to piece together.

Here’s an example from #7 above. Your team is getting ready for a big presentation. The script being developed gets passed around by email. Some people contribute to that document, and the new version gets passed around. Different people are brought in to give their input. The manager wants to make changes and passes it around to multiple people. Different versions of the document fall on the person needing to create the final script. That new version goes out to everyone via email. And the cycle begins again.

While it’s great that there is the speed of distribution, it is bad in that during this review cycle, new people were brought in, different versions were created, and additional reconciliation of the feedback has to take place.

Then the next time a presentation needs to be created. . . the same cycle occurs: establishment of who to involve, the expansion of contributors, and the painful reconciliation of the input takes place again. All because it is so easy to distribute something via email and respond via email.

Given this, it is possible to imagine that there could be a more structured – and efficient – way of getting this done – and without email. The manager could establish who on the team is responsible for creating the document, how it is to be shared, scope who should be the reviewers and contributors, provide a window and focused time to do that reviewing and contributing, and have a decision-making process to get differences resolved. There are better tools these days for sharing documents, but they are for the most part underutilized, or, worse, ignored.

Because we have email, we tend not to create this structure in attempting to get something done. We rely on the ability to communicate and, in turn, establish the de-facto structure to whatever the task at hand is, and we don’t necessarily to create process constraints that could create greater efficiencies, innovation, and quality improvements.

Therefore it is a tenet of the emerging field of Management Design to look at what Managers are doing over email, and determine – is there a better way of doing this? Are there tools and processes that can be established that can better manage the various outputs required of managers, rather than relying on email to establish the process (and then watch that process immediately fade away)?

What kind of management tasks do you do over email? What kind of management tasks do you do that are not over email? Which ones have a more efficient and repeatable process?

Related Articles:

Tenets of Management Design: Focus on the basics, then move to style points

Tenets of Management Design: Managing is a functional skill

Tenets of Management Design: Identify and reward employees who do good work

Tenets of Management Design: Managers are created not found

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field I’m pioneering, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the bad existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, or that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

Today’s tenet of Management Design: Managers are created not found

In an examination of the other “current designs”, there is a tendency to focus on the hiring process.

–Find someone with experience as a manager

–Find someone who acts like a manager

–Find someone who did well as an individual contributor

–Find someone with technical expertise in the area being managed

Tenets of Management Design: A role in management is not an extension of performance as an individual contributor

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field I’m pioneering, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the bad existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, or that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short, often to damaging consequences. We need to turn this around.

Today’s tenet: A role in management is not an extension of performance as an individual contributor

Most people start their careers as an individual contributor (IC). They bring skills that they learned in school or at other organizations, and then develop their skills in their role as an individual contributor, both through initial training and on-the-job experience. As I’ve documented, people in individual contributor roles tend to get lots of performance feedback and guidance on how they’re doing this job. If the manager of the individual contributor is doing her job, the manager is one of the sources providing ongoing, specific and immediate feedback to the individual contributor.

If the manager is doing an even better job, she is also strategically developing the skills of the individual contributor to what the organization needs to be successful.

When this works, this is a good design!

OK, so now how do you find people in management? From individual contributors of course.

Here’s where the mistake frequently occurs:

The management team will identify individual contributors for their skills as individual contributors, and then “reward” them for their outstanding work in this area with a promotion into management. The simple theory is that if the individual contributor could do X amount of positive work as an individual contributor, with a team of say, 3 people, the individual contributor can achieve four times the amount of productivity. That is 3X with direct reports plus the X that the individual contributor could produce. On top of that, the high performing individual contributor is rewarded with a promotion to management, which is typically higher paying and has higher status.

For example, Jim is an amazing business analyst. He creates insightful reports from a series of diverse sources, they are easy to read and understand, and always seem to provide recommendations that are spot on. He also comes up with useful pivots and ratios that allow the decision-making teams to ask in-depth questions that can be answers. The management team wants more. So they promote Jim to Business Analyst Manager, and he inherits a team of three other Business Analysts (Betty, Sarah and Amari), with the idea that they can produce what Jim does on his own to 4X the amount — 80 reports — with Jim-level quality.

That’s the implied theory I’ve observed.

Tenets of Management Design: Drive towards understanding reality and away from relying on perceptions

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field I’m pioneering, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the bad existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, and that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

Today’s tenet of Management Design: Encourage reality over perception

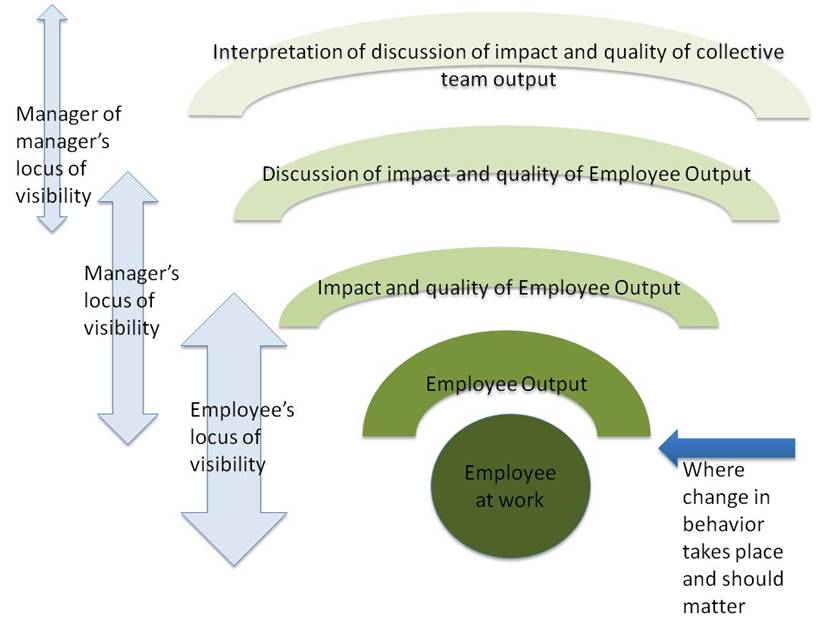

In a previous post, I describe a common situation where employees are evaluated, spliced, diced and put into categories to determine if they need improvement, are high performers, or are in that special purgatory of the middle. The problem with this process is that it requires decisions based on perceptions or, worse, perceptions of perceptions, or perceptions of perceptions of perceptions. This is shown in the “meta slide” of evaluating an employee’s contribution.

This is bad management design. In such a design, managers and managers of managers are charged with the role of doing (what I call) phantom managing — ranking employees — based on argument, rhetoric and perception. Typically, each manager is allowed to bring in their own methods for advocating (or denouncing) their employees, and argues accordingly. This is in the spirit of creating a truth about the employee: Where they fit in the “stack rank,” whether they are “needs improvement” or whether they are “high potential”. The design is, in effect, to create that impression, to create that tag and, for all intents and purposes, institutionalize the worth of the employee as either low, medium or high based on a team of managers’ rhetoric.

Here are some outcomes of this that make this bad, degenerative management design:

- This kind of situation institutionalizes perceptions as the dominant formula for evaluating and tagging employees

- This places an emphasis on evaluation of employees as more important than working with employees to perform at an acceptable level.

- This puts the onus away from the manager and assumes the employee is solely responsible for success in a role

These three outcomes place at a premium the perception of an employee (and what the employee and manager do to manage perceptions), rather than place the focus and emphasis on the reality of the employee’s work output and behaviors.

So instead of focusing on the perceptions, let’s focus on some realities of employee performance:

First, the reality is that no employee can possibly be permanently categorized as low, medium or high. Things are too dynamic – in one situation an employee is great, and in another situation an employee is terrible. Too many times we have observed employees do badly in one context and do great in another (see my article about how to evaluate the system as a part of performance feedback). Does that make the employee good or bad? It’s neither. Putting a tag that risks being a permanent tag creates an unnecessary perceptual problem about the quality of the employee. In addition, that tag, with its trace perception, is likely to carry over year over year.

Next, the reality is that a manager’s role is to do what it takes to make sure the team performs as at high of a level as possible, using the available components of the team, tools, processes and work environment. This evaluative process of tagging employees in one category or another in effect removes that burden from the manager, and creates the perception that the employee capability is the number one factor of team (and manager’s) success, and the rest is out of the manager’s hands. The manager can say, “Well, I have two low performers on my team, thus we couldn’t get it done.” The manager’s real job is not to put those low performers in the low performance bucket, but to figure out how those low performers can contribute to the team to make the team effective. If those low performers are that bad, are a terrible fit, and shouldn’t even be on the team, there is the option of performance managing the low performer. Instead, too many managers wait until the end of the year, exact their revenge on the low performers by saying, “Well, they are low performers!” And sure enough, that low performer appears the following year as a low performer. The manager’s role? Declaring them as low performers.

Third, the reality is that the manager has a huge impact on the individual contributor’s performance, perhaps as much as the individual contributor has on his performance. The manager who sets up expectations well, who assures that there are processes that drive a consistent strategy, who discourages drama and who encourages teamwork will make any set of employees better. These are managers who can turn a team of average performers into a team of star performers (who then get tagged as “high potential” – until those high potentials go into a broken system, then lo and behold they become low performers). Obviously the individual contributors need to bring their “A” game to make a truly high performing team, but with current management design, there is an assumption that every team needs to be filled entirely with Michael Jordans and Zinedine Zidanes to be successful. Simply not the case, as even Messrs. Jordan and Zidane, with all of their success, never had such teams.

Drive the focus toward the reality of an employee’s output

So instead of engaging in meta-perceptual conversations about the relative worth of each employee, good management design should discourage structures that solidify perceptions, and push the manager to the reality of creating as strong a team as possible, focusing on the behaviors of each team member, and getting as close as possible to the reality of the team performance.

The dark green circle is the closest we can get to understanding reality. In good management design, the focus should be that managers think and deal with the employee at work, and try to get the behaviors to the maximum effectives, both as an individual and as a team. The manager still has a few degrees of separation from direct understanding of the reality of the employee’s work, but instead of encouraging moving further away from it, good management design should encourage getting closer to it.

Tenets of Management Design: Identify and reward employees who do good work

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field this blog pioneers, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the poorly performing existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, or that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

So today’s tenet of Management Design: Design ways that managers consistently identify and reward employees who do good work

This seems like a somewhat obvious tenet that should occur naturally in any organization. The employees who do good work should be identified and rewarded. However, it doesn’t seem to work out that way enough. How many times have we seen it that underperforming employees jockey for visibility and accolades, while the high performing employees feel like they are being ignored or taken for granted? How many times have we seen managers not give thanks or offer praise when it is well earned?

Tenets of Management Design: Focus on the basics, then move to style points

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field I’m pioneering, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the bad existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, or that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

So today’s tenet: Focus on basic tasks of people and team management, then move to style points

I introduce the concept of style points as a way of prioritizing what goes into creating great managers, and the steps that should be taken to get to the status of “great manager.” Style points are the flourishes that can be performed if you have successfully completed the fundamentals, the basics, or the preliminary tasks. Someone who tries to go for style points without having mastered the basics can look pretty foolish. Unfortunately, this tends to happen a lot with managers, both new and experienced. If you have ever rolled your eyes in response to a manager’s actions, then it likely he or she was trying get style points prior to having done something more basic.

Tenets of Management Design: Managing is a functional skill

In this post, I begin to explore the tenets of the new field I advocate called Management Design. Management Design is a response to the bad, or lazy, existing design (cataloged here) that currently describes how managers are developed or found. These existing designs demonstrate how people managers are often created by accident, rather than by design. To improve this, I’m proposing design tenets and here’s the first tenet of management design: Treat people and team management as a functional skill. Read more