How to use the What-How grid to build team strength, strategy and performance

In my previous post, I described how managers can use the What-How grid to identify a more complete view of performance of their team members. In the posting, I discussed how this grid aids managers in identifying which areas of performance feedback they should be receiving. In this post, I’ll discuss how you can further use the grid to make better strategic decisions in running your team.

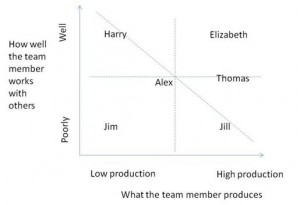

When you use the What-How grid, you create a view of your team that identifies where the strengths lie on the team:

In this example, the team is distributed all over the graph, but it is easy to imagine a team that is clumped together in different spots in the grid.

A key benefit to having this view is that it helps you strategize on what you expect your employees to produce, and whom you ask them to interact with. For example, if you have a high producer who can’t work with others, then don’t put them in a position where working well with others is crucial. OK, that seems obvious, but how often do organizations put the “technical expert” in front of important clients, only to have the expert make interpersonal mistakes? If you have a role on your team where someone has to be purely customer facing, then this might be a role that the “popular but low producing” person may reside. (In this case, what they produce needs to be revised, and make sure that they create some sort of results, rather than just make friends.)

In any case, all of your employees need to have some combination of both “the what and how” to be a net positive to the team (above the diagonal line on the graph). If they are below the line in one dimension, they are, by definition, more risky employees, and need to be monitored more closely. In many organizations, these “one dimensional” employees tend to be evaluated less closely, since they are so strong in their preferred area. This creates peril!

When you know who is strong in the “interaction” area and who is strong in the “technical” area, you can foster teamwork better. In creating plans for how the team interacts, you can be specific as to why you are putting one person in position that is more customer-facing and as the manager, you can create expectations for how the more technical people can support (provide information, prepare) the person in his efforts. Note that for this to work, everyone should have minimal ability in both dimensions (to get above the diagonal line), because if you have someone who is too one-dimensional, you’ll perpetually struggle to have a productive team.

Another strategic area where this can be used is in making hiring decisions. If you have a group of people who are clumped too far in the upper left or lower right quadrants, then you should consider adding a complement to these “strengths” on the team. Further, when you make this strategic move, you have awareness of what it is that you expect the person to do in relation to the others—to complement their skills. This allows you to foster teamwork and create smarter workflows on the team.

Finally, if you have an underperformer in both dimensions, you can be smarter in deciding what you expect that underperformer to do as part of their job, rather than treat them as an equal performer to those who have greater abilities. Plus, in deciding how you will work to increase their skills, you can be smarter in enlisting help in improving their performance. If you decide that the underperformer needs better technical acumen (and that is the greatest need on the team, let’s say), you can assign a more technical person on your team to mentor the underperformer in this area (and make it clear that this is what you expect the mentoring to be about).

For those aspiring management designers out there, is plotting the person on this grid something that you expect your managers to perform? Or must managers come up with this assessment method themselves, risking the error that employees are assessed only across one dimension?

For you managers out there—have you ever plotted your team across both the “what” and the “how” in making strategic decisions? What other strategic plays can you see a manager making using the what-how grid? How have you used it in the past?