Management Design: The designs we have now – Manager knows and supports only one possible strategy

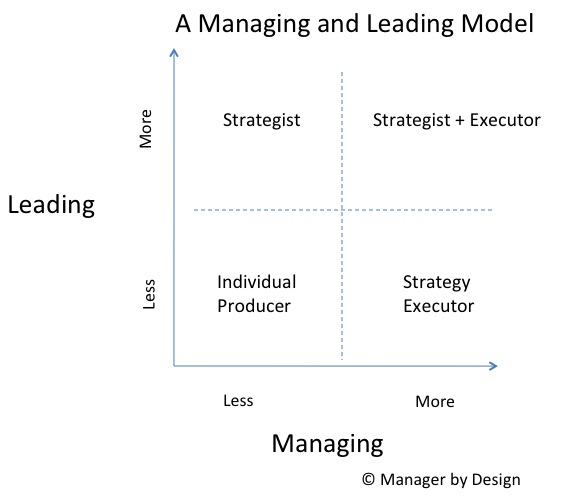

In my previous article, I showed a model I created that identifies the difference between being a leader and a manager. Here it is:

In this model, the manager that I typically think of when writing about managers is in the lower right corner – a manager who is a “Strategy Executor.” The organization that the manager works for has a strategy, and the manager makes sure that this strategy is executed. This manager typically has a team of people in some capacity (either direct reports, virtual, outsourced vendor) to make sure the strategy is executed.

As an example, if you are a Training Manager, then the strategy is that the organization is using “Training” as a means to help the organization run better. “Training” is the Strategy, and the Training Manager is needed to execute that strategy.

So the training manager has to make sure the training is executed. That means there needs to be budget, a team of people and facilities to get this done somehow. That’s the manager’s job – use these resources to execute the “Training” Strategy.

But how does one become a strategy executor, a.k.a., manager? There are various paths.

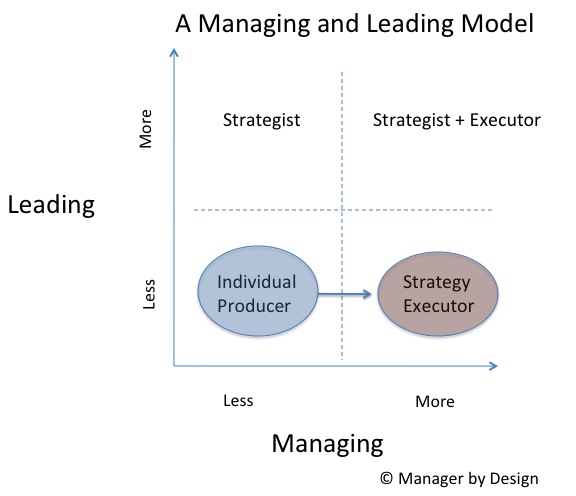

The most commonly thought of path is the following:

- Someone is really good at being an individual producer, and the manager role opens up, and they get the job as the manager. That individual producer is now the strategy executor. Here’s how it looks on the model:

This seems to fit in the popular conception of how people become managers, but under this model, you can see a potential design flaw. The person becomes a manager without having been involved with the strategy development. In the case of the Training Manager, the strategy executor will be executing the “Training Strategy” without really knowing what went into the development of that strategy.

Managers: Know your change events and track these

When you are a manager, one of the things that you are responsible is the ongoing improvement of your team and how it operates.

Now, with that expectation set, are you tracking the “change events” that account for and assess this?

Change happens on a team and in a group all the time. In fact, it happens so often that it is easy to lose track of all of the change that is happening.

Here are sample “change events” that could constitute change on your team:

- A new person or joins the team or someone leaves the team (or many people join or leave the team)

- A new budget is implemented

- Your organization or your team launches a strategy

- There is a process improvement or process change

- There is a change in scope of work

- A new project starts or an old project ends

- There is a new environment or element to the work environment (change in office space or new equipment)

Some of this change is instigated by the manager, and some of it is implemented by external events, either from above or by the passage of time. It’s all change, and it needs to be understood as such.

So the first task of understanding change is to track these events. If you don’t do it as a manager, perhaps someone on your team can track these events. Having these change events documented and tracked creates a better understanding of what your team is handling.

So here are some suggesting things to track for your team change:

- Item number

- Source of change

- Change description

- Initial date of learning of change

- Expected positive impact

- Expected negative impact

- Who is responsible for delivering the change

- Who is involved

- Change plan location

- Change implementation / assessment date

Here’s what it may look like on a spreadsheet

| Item Number | Change description | Source of change | Initial Date of learning of change | Expected positive impact | Expected negative impact | Who is responsible for delivering change | Who is involved | Change plan location | Change implementation / assessment date |

| 1 | Marci leaves | Marci | 6/1/2011 | Opportunity to identify emerging team needs and hire to it | Lose Marci’s skill set | Manager hiring | Manager, HR, Team Members | Hiring process site | 7/1/2011 (replacement hired) 12/1/2011 (up to speed) |

| 2 | New quality assurance program | Manager initiated | 3/1/2010 (kick off of implementation) | Improved quality | Resistance/inertia of prior system, less efficiency | Alex | All team and partner teams | Team site : projects | 12/1/2011 (program implemented) 3/1/2011 (assess quality) |

| 3 |

What to do when someone on your team resists change (part 2)

In my previous article, I describe the importance of not attacking a change agent, but instead taking steps to manage the change, not the change agent. Many managers receive “feedback” that is resistance to change, and then turn around and give that feedback to the change agents, implying that the manager doesn’t actually want the change agent to instigate the change.

The first five steps to this were: 1. Listen 2. Document the issue 3. Track the issues. 4. Delay in responding to them 5. Look at the issues as a team.

Today, I provide tips on what to do next:

6. Communicate your findings – the more targeted the better

You typically know the source of the resistance/complaint. You tracked it, right? Now you can respond directly to that person. Explain what you did (discussed it as a team) and what you plan to do (keep going with the change, most likely). I am not a fan of communicating broadly the list of concerns and the responses, because it is somewhat akin to public feedback. By communicating broadly, you are trying to adjust the thinking for a specific person via communicating with a broad group. This creates unintended consequence of changing the broad group’s thinking when it isn’t necessarily a problem. It’s better to circle back to the person who expressed the concern in the first place. If there is a network of people who believe the same thing, that person then gets to address the results.

What to do when someone on your team resists change (part 1)

Many managers are in the position of instigating and overseeing change on the team, with the intent that this change improves how things are done and obtains better results.

But managers can quickly fall into the trap of resisting the change they instigated by reacting negatively to the ramifications of change, and seeking to eliminate all resistances (a.k.a., complaints) to the change.

They do this by treating incoming complaints of the change agent as a performance feedback opportunity to the change agent. This implies that the change can occur and without resistance and essentially undermines the change effort. This is a wrong assumption – it’s like assuming that there is no resistance when you start a car and move forward.

So here’s what to do when someone on your team resists change:

1. Listen

Allow the person to hear out the person’s issues with the change. The only action is to listen to the issues or complaints that the person has. Instead of responding to the issue, listen to the issue. Say, “Thank you for expressing your concerns.” Add some empathy, “I understand that this can be difficult.”

2. Track the concerns

To prove that you are listening, actually write down the concerns. Write them down in front of the person expressing them. Tell them that you are writing them down. Say, “I appreciate your taking the time to express these concerns. I’m going to make sure I have your concerns tracked, is that O.K.?”

3. Put the concerns in a central location

You probably aren’t the only one receiving complaints. Upon the first complaint, this is your clue that there may be more. Find a place for others on your team to document them. Put them in the same place.

Are you asking a change agent to make a change, and then resisting the change?

Many managers want to get great results. To do this, they seek and find high performers who drive toward these results. One way a high performer can achieve great results is through creating and implementing structures and processes that provide ongoing value and systemic improvement. Or, in other words, change.

The high performer is a change agent. This is what managers want. Managers want change for the better, and rely on the “high performers” to instigate and implement the change. That’s what makes them a high performer.

But there is a mistake that many current managers make in seeing this model through: They give feedback to the person instigating the change that there is resistance to the change. This is a flaw in current management design, and one that is all too common.

Here’s what I mean:

When change occurs in an organization, there inevitably will be complaints about the change. The complaints will be about whoever is instigating the change. It doesn’t matter if it is good or bad change, people somewhere in the organization will be resistant to the change. This is normal and part of the “change curve.” The complaints will be inevitably be about the person instigating the change. That was supposedly the high performer, who was encouraged by the manager to create the change.

Using perceptions to manage: How this undermines efforts for change

This is the latest in a series of articles about how using perceptions in managing a team can be a recipe for disaster.

Think about the manager who says, “There’s a perception that you expect too much of other people” or “There’s a perception that you are not very well liked.” This is the manager attempting to manage perceptions and not behaviors, and is something that needs to be banned from the manager’s vocabulary. I provide reasons here, here, here, here and here (there’s a perception that this is a very thorough series!).

In today’s article, I discuss how negative perceptions are often a symptom of positive change:

In a previous article I discuss the scenario of Arnold, a team member that provided suggestions and helped implement changes on a team that produced greater productivity and lower cost. In the process, there were some negative perceptions about Arnold, “You’ve done a lot of things since joining the team, but there’s a perception that you want to change things too fast, and that you expect the team to do too much.” Let’s take a look at what this means:

Citing perceptions often reveals change agents at work and then undermines them

If a manager can cite only negative perceptions of someone as the negative impact, then this could be an indicator that the person could actually a positive change agent in the workplace. Many people are resistant to change, and when someone brings it to the organization, that resistance will manifest as undifferentiated negative perceptions that quickly propagate through the organization. The actual change may be good and improve things, but with any change the initial perception is that the change is bad in some way.

More reasons mandatory meetings are bad for you and bad for your team

In my previous post, I discussed why mandatory meetings create a bad dynamic for your group or your team. The post centered on the cycle that the people who don’t want to attend – the ones that compelled you to make it mandatory – end up sabotaging your meeting anyway, making it a bad experience for you, the ones who wanted to attend, and the ones who didn’t want to attend.

But there are more reasons you should consider not making any meetings mandatory. And here they are:

Reason number 1: You can’t get everyone to attend anyway

This is an obvious point, but one that seems to be lost on many managers who require attendance at meetings. For any given meeting, there is going to be a group of people who will not or cannot attend. Read more

A change agent brought in from the outside needs more than being a change agent from the outside

In my previous post, I explored the management “design” of hiring someone from a successful organization to bring change to your org. It’s a great idea – hire from the best, and you get the best. And presumably, this person is a top performer. Win-win! However, this can be a perilous design, as the organization you’re hiring from perhaps created great performance through the org processes and culture. The success was not necessarily via the individual’s greatness, but from the collective efforts of the previous org. But that’s what you’re hiring for when you hire this kind of expertise – change and improvement. So you need to be committed to it.

Let’s imagine that you hire a change agent who is ready to bring in the successful ideas and practices of the prior org to the new org. What more needs to be done to help this change agent be successful? Let’s take a look. Read more

Management Design: The “designs” we have now: Recruit someone from a successful comparable organization

The Manager by Designsm blog advocates for a new field called Management Design. The idea is that the creation of great and effective people managers in organizations should not occur by accident, but by design. Currently, the creation of great managers falls under diverse, mostly organic methods, which create mixed results at best and disasters at worst. This is the latest of a series that explores the existing designs that create managers in organizations. Today’s design: Hire someone from a successful comparable organization, such as a competitor. Read more