On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

Today I want to talk about a management team and how it relates to employees. Imagine the management team. They are in charge of the project of evaluating the performance of their collective employees. In some organizations, they are asked to “stack rank” all employees in an organization, or at least put them in general categories, such as low performer, average performer, high performer, or some variation like, “Needs improvement” at the bottom of the rank to “High Potential” at the top of the rank.

OK, now the management team needs to do the work of ranking the employees. The person facilitating this process is likely to be the manager of the team of managers, or the manager above that. So you have a bunch of managers in a room discussing a large batch of employees’ performance, making arguments about who is a good performer, who is an average performer and who is a low performer. Oftentimes there is a forced curve that requires some people into the “needs improvement” bucket. Oftentimes these discussions have promotion implications and bonus implications. In the examples of companies that have adopted the “fire the lowest 10%” philosophy, it also has firing implications.

Inevitably, the employees know that this kind of thing is happening between the managers. This is a common practice at many large organizations, and a tough one to get right. I’m not really sure it is possible to get right, and here’s why.

In a discussion like this, each manager is armed with some data about the employee. As discussed frequently in this blog, that data about how an employee performed is limited at best, and non-existent at worst.

There are cases where there are specific metrics that are directly comparable across employees, and a certain amount of fairness can be achieved by this measure. This typically occurs with employees at the lower level of an organization, and if you have several employees doing similar or repetitive work that produces comparable metrics. This is decreasingly the case, however, as even – or especially — entry-level positions require more quality-minded, customer-oriented, problem-solving type thinking to achieve high-pressure work goals. So even when there are directly comparable metrics, there are many intangibles that come into play.

So inevitably, it seems that current management design requires that managers get in a room and essentially argue who is the best employee, whether they deserve a raise, and, in many cases, argue that the other employees are less deserving.

Now, what’s tough is that these decisions are way out of the employee’s control – even if they have done amazing work through the year.

Here’s why:

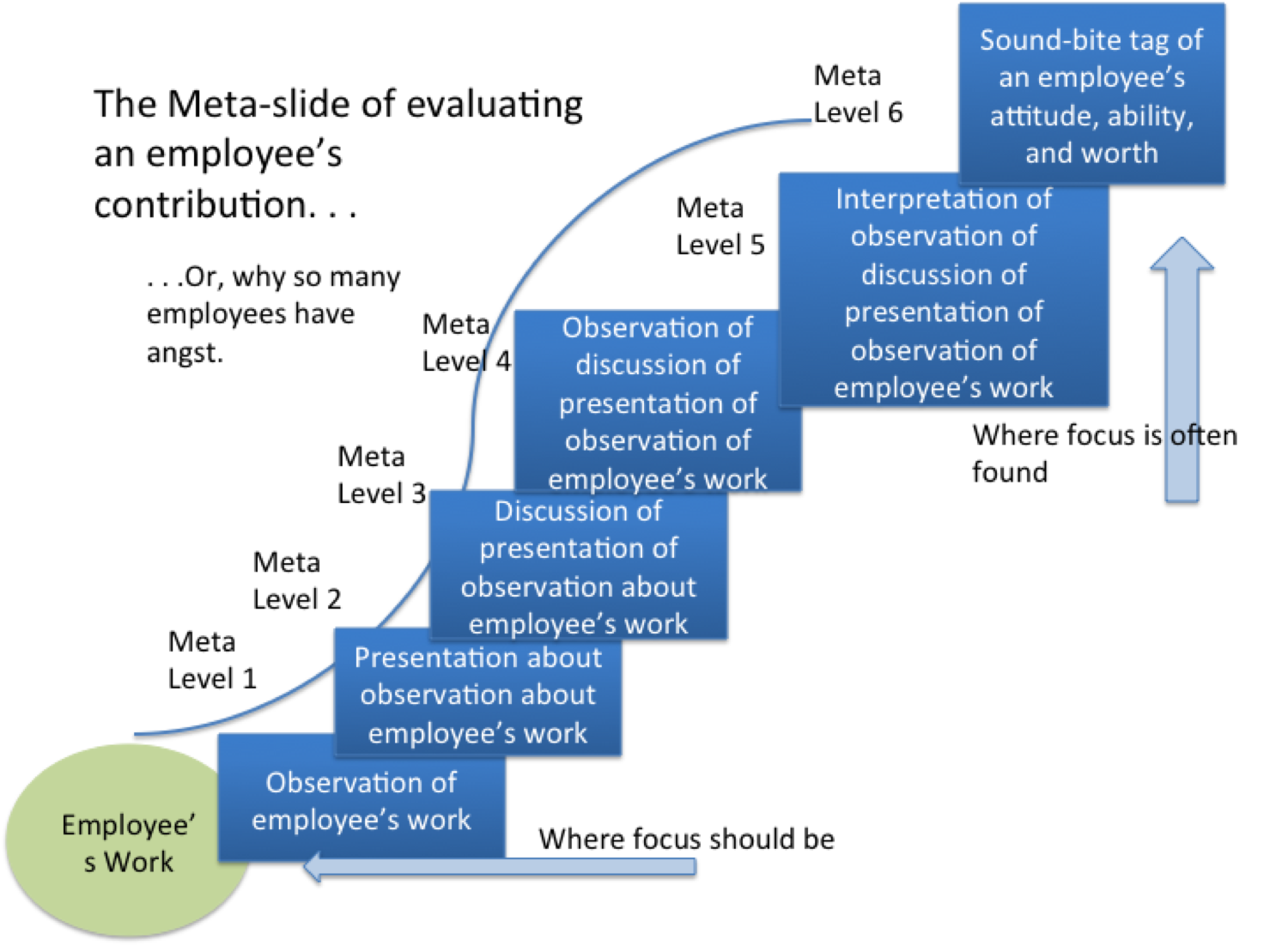

The discussion is inevitably a summary statement of everything an employee has done through the year, and that summary statement cannot possibly be true. In the “stack rank” discussion, a certain amount of meta-analysis of the employee’s performance and worth is required. Here’s what I mean:

How to use strategy sessions as a way to manage indirect sources of info about your employees (part 3)

This is the third part of a three part series in which I describe how managers should use strategy sessions to address indirect sources of information. Many managers react to indirect sources of information and pass it along as feedback, when instead they should focus on direct sources of information for providing performance feedback. When dealing with indirect sources of info, I advocate for “strategy sessions.”

In the example I’m using in this series, you’re receiving information from your employee’s peers and partners that the employee is being “difficult” in meetings. In my previous articles (part 1 here, and part 2 here), I describe the first six steps for managers to take:

1) Make sure it’s important and worth strategizing about

2) Introduce the conversation as a strategy session

3) Introduce the issue that needs to be strategized share the information that is driving the need for discussion

4) Ask for the employee’s perspective on what the issue is

5) Find points of agreement on what the issue is

6) Strategize on how to resolve the problem

In today’s article, I wrap up the steps for conducting a strategy session with your employee:

7. Agree on what both of you plan to do differently

Since you never directly observed the original behavior, you can’t give quality feedback on the behavior. You can, however, agree on what should be done moving forward. This is a form of providing expectations of behavior. As a result of the strategy session, you and your employee may agree to the following:

How to use strategy sessions as a way to manage indirect sources of info about your employees (part 2)

This is the second of a three part series in which I describe how managers should use strategy sessions to address indirect sources of information about their employees. Many managers react to indirect sources of information and pass it along as feedback, when instead they should focus on direct sources of information for providing performance feedback. When dealing with indirect sources of info, I advocate for “employee strategy sessions.”

In the example I’m using in this series, you’re receiving information from your employee’s peers and partners that the employee is being “difficult” in meetings. In my previous article, I describe the first three steps for managers to take:

1) Make sure it’s important and worth strategizing about

2) Introduce the conversation as a strategy session

3) Introduce the issue that needs to be strategized share the information that is driving the need for discussion

In today’s article, we continue the steps for conducting a strategy session with your employee:

4. Ask for the employee’s perspective on what the issue is

You can say, “I’d like your perspective on what the issue is and what is creating it.” In our example, others may find the employee difficult, but perhaps the others are being difficult to the employee. You don’t know, so provide ample space in the conversation for the employee to explain his or her perspective. You will likely get more robust information than you probably got from the “indirect” sources. The better the manager listens and understands the employee’s perspective, the more trust will be built between the employee and the manager. In many instances, the employee will fully admit to being “difficult” and will explain what their behavior was that would be interpreted as such. But the strategy session is about resolving the issue – not only the employee’s behavior. So make sure you get the employee’s perspective on what the issue is.

How to use strategy sessions as a way to manage indirect sources of info about your employees (part 1)

This is the first part of a three part series on how managers can use “strategy sessions” to improve the performance of their employees and their team, as well as the manager’s own performance.

Managers receive a lot of information about their employees from indirect sources – often much more information than from direct observation. I frequently write about how it is important that performance feedback be performed based on direct observation, or else it risks being non-specific and non-immediate, and generally becomes useless the less specific and less immediate it is.

However, managers are not often enough in the position to observe directly what it is the employee did exactly and provide this level of performance feedback. And with all of the indirect information floating around – such as from customers, other employees, bosses and metrics – it becomes difficult to figure out what to do about it.

Here’s an example I’ll use throughout this series: You are getting “feedback” from your employee’s peers and partners that he was “difficult” during a recent series of meetings. You’d like to give feedback on this. But what is it exactly that was “difficult” and why is this happening? And maybe this “difficult” behavior was actually a good thing? You really don’t know.

My recommendation is, instead of having a “feedback conversation”, have a “strategy sessions” with your employee. The idea with strategy sessions is that you partner with your employee to figure out the best course of action moving forward to address the “feedback” (actually, it’s an indirect source of information) and still achieve the goals. In short, you and your employee strategize together.

This is different from delivering corrective feedback, which is more direct, specific and immediate, with a clear course of behavioral actions that are different the next time it is performed. Strategy sessions are more along the lines of “What should we do to get the best outcome?”

Here are the first three steps on conducting strategy sessions with an employee:

What to do when you receive a customer complaint about your employee’s performance

In my previous articles, I provide warnings to managers who rely on indirect sources of information about employees’ performance in providing performance feedback. I generally advocate that a manager use direct observation to provide performance feedback, as this is the path that most likely will generate improved performance. Relying on indirect sources tends to erode trust and is often very confusing. I provide some tips on what to do about “indirect sources” here.

But there are times when you receive some sort of feedback about your employee’s performance that doesn’t allow you to wait until you can notice a trend and/or perform more direct observation. A common scenario is when you receive a complaint from a customer about something one of your employees has done. So let’s talk about what to do in this scenario!

1. Get info from the customer about what happened.

When a customer complains to you about what the employee did, try to get the points of fact about the situation, what was said and done during the situation, and where things stand now (has the issue actually been resolved, or does it still need resolution?”) Often with complaints – and if you are speaking directly with the customer – the details are fairly fresh in the customer’s mind – and usually given right away after the situation, so it is possible to get fairly specific quotes about what your employee said, specific info about what your employee did. Try to write these quotes/actions down and understand as many of the “facts” of the situation possible. Of course, if you receive this complaint indirectly (like via a survey), then this option is not available.

2. Resolve the customer issue/inform that you will take action

When a customer complains, there are often two complaints wrapped in one. Read more

Tips for how managers should use indirect sources of information about employees

In my previous articles, I’ve provided warnings about using indirect sources of information about your employees to provide performance feedback. The reasons are numerous, some of which are provided here and here. Indirect sources of information about your employees performance may include “feedback” from sources such as customers, peers or your boss. We may call this “feedback”, but it isn’t really feedback, since it is, by definition, time delayed and usually non-specific. This makes it, for the most part, non-actionable. So this information – while copious — doesn’t merit the high bar that is “feedback.” However, this is information about your employee, so let’s look at some ways to maximize the value of this information – instead of just passing it along as non-specific and non-immediate “feedback.”

What to do with indirect information about your employee

a) Try to get more info

If you get some sort of “feedback” about your employee, at least try to get information about what it is that the employee did to earn the feedback.

Let’s say your boss tells you that your employee, John, “Nailed it this week.”

Bonus! Six more reasons why giving performance feedback based on indirect information is risky

I’m a big advocate for managers to give performance feedback to their employees. But the performance feedback has to be of good quality. So let’s remove the sources of bad quality performance feedback. One of these is what I call “indirect sources” of information. These include customer feedback, feedback from your boss about your employee, the employee’s feedback. These are all sources of information about your employee – and provide useful information, but they are not sources of performance feedback.

In previous articles, further outlined what counts as direct source of information about an employee’s performance (here, here, and here). And in my prior article, I describe how indirect sources are, by definition, vague, time-delayed, and colored by value judgments, making them feedback sources that inherently produce bad performance feedback when delivered to the employee.

There are more reasons a manager should hesitate using indirect sources of info as “feedback.” Let’s go through them.

1. Have to spend a lot of time getting the facts straight

Let’s say your boss tells you that one of your employees, Carl, did a “bad job during a meeting.” The natural tendency is to give feedback to Carl about his performance, using the boss’s input. When sharing feedback from this indirect source, you will need to go through a prolonged phase of getting the facts straight. First you have to figure out the context (what was the meeting about?), then you have to figure out what the employee did, usually relying on some combination of what the feedback provider (not you) observed, which, is typically not given well, and what the employee says he did. This usually takes a long time, and by the time you’ve done this, you still aren’t sure as to what the actual behaviors were, but an approximation of the behaviors from several sources. So the confidence in feedback of what to do differently will be muted and less sure.

Three reasons why giving performance feedback based on indirect information doesn’t work

In my previous articles, I advocate that managers provide performance feedback based on direct observation. This way, the feedback is more likely to be specific, immediate, and behavior-based. All good things. The best sources are observation during practice, direct observation during a performance, and tangible artifacts.

Yet, managers receive lots and lots of data about employees’ performance from indirect sources: Other employees, customer feedback, the “big boss.” I generally advocate that managers refrain from “giving feedback” based on indirect sources of information, because they have some serious disadvantages:

(This article uses examples of the boss’s boss giving feedback about an employee, but the same goes for peer feedback or customer feedback given to a manager.)

1. Indirect feedback tends to provide non-specific summaries and vague generalizations.

Let’s say your boss likes one of your employees a lot. She tells you, “John really nailed it this week.” This is great! But you have no idea what it is that John did that earned this praise. Giving feedback to John on this – even when positive — is kind of awkward: “I have some feedback for you, John. Sarah says that you ‘nailed it’!” It’s great to give the praise, but without the specifics, it doesn’t make much sense. John will say to himself, “Okay, I’m not sure what I did, but I’ll take it.”

In the negative example, when the boss says, “John is screwing up, do something about it,” the manager is in the situation where it seems like performance feedback is necessary, but on what? Even though it is “from the boss,” recognize that it’s incomplete and vague. (If the boss’s boss were a “manager by design,” this kind of non-specific feedback wouldn’t be given, and would be more behavior-based.)

What managers can do about “intangible human-based artifacts”

This is the latest in a series of articles on what inputs a manager should provide performance feedback on. The three best sources are practice sessions, direct on-the-job observation, and “tangible artifacts”. The reason these are the best input to provide performance feedback on is that these are the closest to the performance, hence performance feedback is possible. The intent of providing performance feedback is that this feedback will help performance improve. The better the feedback, the more likely the performance is going to improve.

It’s a fairly simple model that often gets messed up. Here’s why:

After “tangible artifacts,” there the are lots of other thing that employees produce — and managers receive a lot of input about an employee from these – but, as the label implies, these are less tangible (see this article for a general overview) and therefore less useful for providing performance feedback on. So let’s talk about perhaps the most common of these inputs, what I call “intangible human-based” artifacts and how managers should use them.

Intangible, human-based artifacts:

There are intangible artifacts related to the people they work with that an employee produces. These are things like “relationships” or “valued customers” or “buy-in from a partner” or “sales.” These are all human-based outcomes that the employee can “produce,” and in many jobs, these are the thing that the employee must produce.

Since these are human-based “artifacts”, a manager looking at the artifact – i.e., talking to the person or seeing the person’s comments from a survey — is seeing only an indicator of performance, and not the performance itself. Here’s what I mean:

Imagine walking in at the end of a dance performance. The performance is over and you see the crowd stand up and clap and yell, “Bravo!” The dancer created the intangible human-based artifact of the “delighted audience.” Awesome!

This is clearly an indicator that the dance performance went well, but you cannot provide performance feedback to the dancer. You can comment on the audience’s reaction, “Wow, the crowd really loved the performance!” But you are still perhaps curious as to what the performance looked like, and the best you can do is inquire to the dancer, “Did you do all of the steps as we discussed?” It’s better to watch the actual performance so you can say, “I loved that massive jump you did during the finale – such extension!”