How to be collaborative rather than combative with your employees – and make annual reviews go SOOO much better

Many managers botch the annual review process. There’s this persistent idea out there that the manager needs to provide “one good thing, one bad thing” on an annual performance review. However unlikely it is that the employee does an equal amount of damage as good over the course of the year, this model seems to persist. Many times, managers will actually go fishing for incidents that are bad. They’ll try to find those moments where the employee said something wrong, missed a step, or caused friction on the team. The manager will fastidiously wait for the annual review and then spring it upon the employee – Aha! You did this bad thing during the year! And I get to cite it on the review.

Well no more of that!

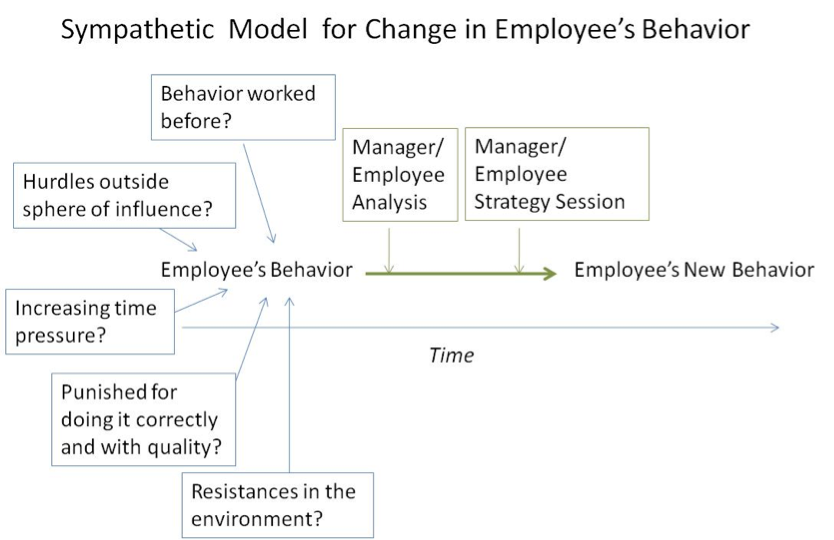

I propose the sympathetic model of performance feedback. In the sympathetic model, the manager looks at both the individual and the system in determining what the employee ought to have done differently (if anything) and what ought to be done differently in the future.

Here is the sympathetic model: (Click for larger image)

When you look at an employee’s actions this way, you can see that there may be some greater forces that went into the employee’s behavior. So instead of using a bad incident to cite what is wrong with the employee, the sympathetic model asks that managers engage in analysis and discussion with the employee to figure out what drove the behavior. Then the manager and the employee strategize on what to do next, and what should be done in the future.

Tenets of Management Design: Drive towards understanding reality and away from relying on perceptions

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field I’m pioneering, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the bad existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, and that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

Today’s tenet of Management Design: Encourage reality over perception

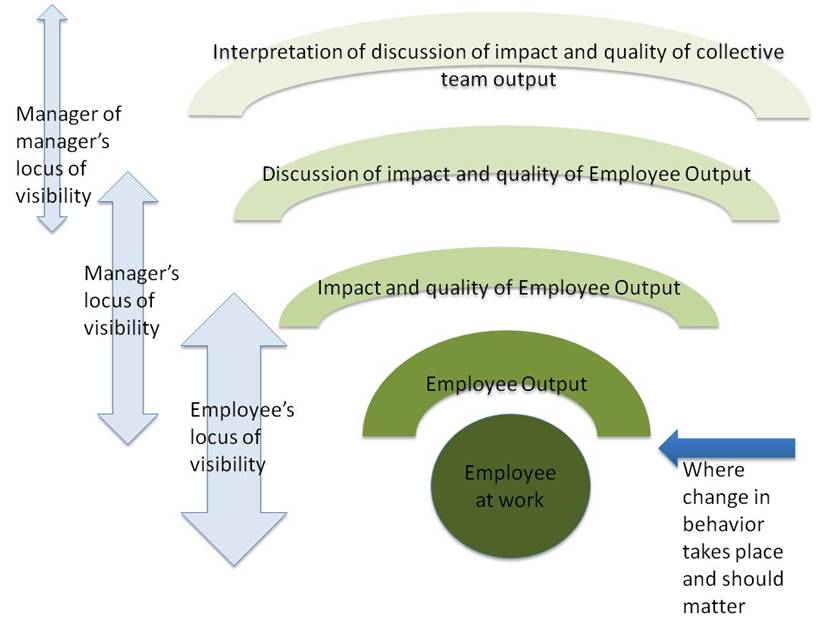

In a previous post, I describe a common situation where employees are evaluated, spliced, diced and put into categories to determine if they need improvement, are high performers, or are in that special purgatory of the middle. The problem with this process is that it requires decisions based on perceptions or, worse, perceptions of perceptions, or perceptions of perceptions of perceptions. This is shown in the “meta slide” of evaluating an employee’s contribution.

This is bad management design. In such a design, managers and managers of managers are charged with the role of doing (what I call) phantom managing — ranking employees — based on argument, rhetoric and perception. Typically, each manager is allowed to bring in their own methods for advocating (or denouncing) their employees, and argues accordingly. This is in the spirit of creating a truth about the employee: Where they fit in the “stack rank,” whether they are “needs improvement” or whether they are “high potential”. The design is, in effect, to create that impression, to create that tag and, for all intents and purposes, institutionalize the worth of the employee as either low, medium or high based on a team of managers’ rhetoric.

Here are some outcomes of this that make this bad, degenerative management design:

- This kind of situation institutionalizes perceptions as the dominant formula for evaluating and tagging employees

- This places an emphasis on evaluation of employees as more important than working with employees to perform at an acceptable level.

- This puts the onus away from the manager and assumes the employee is solely responsible for success in a role

These three outcomes place at a premium the perception of an employee (and what the employee and manager do to manage perceptions), rather than place the focus and emphasis on the reality of the employee’s work output and behaviors.

So instead of focusing on the perceptions, let’s focus on some realities of employee performance:

First, the reality is that no employee can possibly be permanently categorized as low, medium or high. Things are too dynamic – in one situation an employee is great, and in another situation an employee is terrible. Too many times we have observed employees do badly in one context and do great in another (see my article about how to evaluate the system as a part of performance feedback). Does that make the employee good or bad? It’s neither. Putting a tag that risks being a permanent tag creates an unnecessary perceptual problem about the quality of the employee. In addition, that tag, with its trace perception, is likely to carry over year over year.

Next, the reality is that a manager’s role is to do what it takes to make sure the team performs as at high of a level as possible, using the available components of the team, tools, processes and work environment. This evaluative process of tagging employees in one category or another in effect removes that burden from the manager, and creates the perception that the employee capability is the number one factor of team (and manager’s) success, and the rest is out of the manager’s hands. The manager can say, “Well, I have two low performers on my team, thus we couldn’t get it done.” The manager’s real job is not to put those low performers in the low performance bucket, but to figure out how those low performers can contribute to the team to make the team effective. If those low performers are that bad, are a terrible fit, and shouldn’t even be on the team, there is the option of performance managing the low performer. Instead, too many managers wait until the end of the year, exact their revenge on the low performers by saying, “Well, they are low performers!” And sure enough, that low performer appears the following year as a low performer. The manager’s role? Declaring them as low performers.

Third, the reality is that the manager has a huge impact on the individual contributor’s performance, perhaps as much as the individual contributor has on his performance. The manager who sets up expectations well, who assures that there are processes that drive a consistent strategy, who discourages drama and who encourages teamwork will make any set of employees better. These are managers who can turn a team of average performers into a team of star performers (who then get tagged as “high potential” – until those high potentials go into a broken system, then lo and behold they become low performers). Obviously the individual contributors need to bring their “A” game to make a truly high performing team, but with current management design, there is an assumption that every team needs to be filled entirely with Michael Jordans and Zinedine Zidanes to be successful. Simply not the case, as even Messrs. Jordan and Zidane, with all of their success, never had such teams.

Drive the focus toward the reality of an employee’s output

So instead of engaging in meta-perceptual conversations about the relative worth of each employee, good management design should discourage structures that solidify perceptions, and push the manager to the reality of creating as strong a team as possible, focusing on the behaviors of each team member, and getting as close as possible to the reality of the team performance.

The dark green circle is the closest we can get to understanding reality. In good management design, the focus should be that managers think and deal with the employee at work, and try to get the behaviors to the maximum effectives, both as an individual and as a team. The manager still has a few degrees of separation from direct understanding of the reality of the employee’s work, but instead of encouraging moving further away from it, good management design should encourage getting closer to it.

Management Design: How managers receive performance feedback compared to other jobs

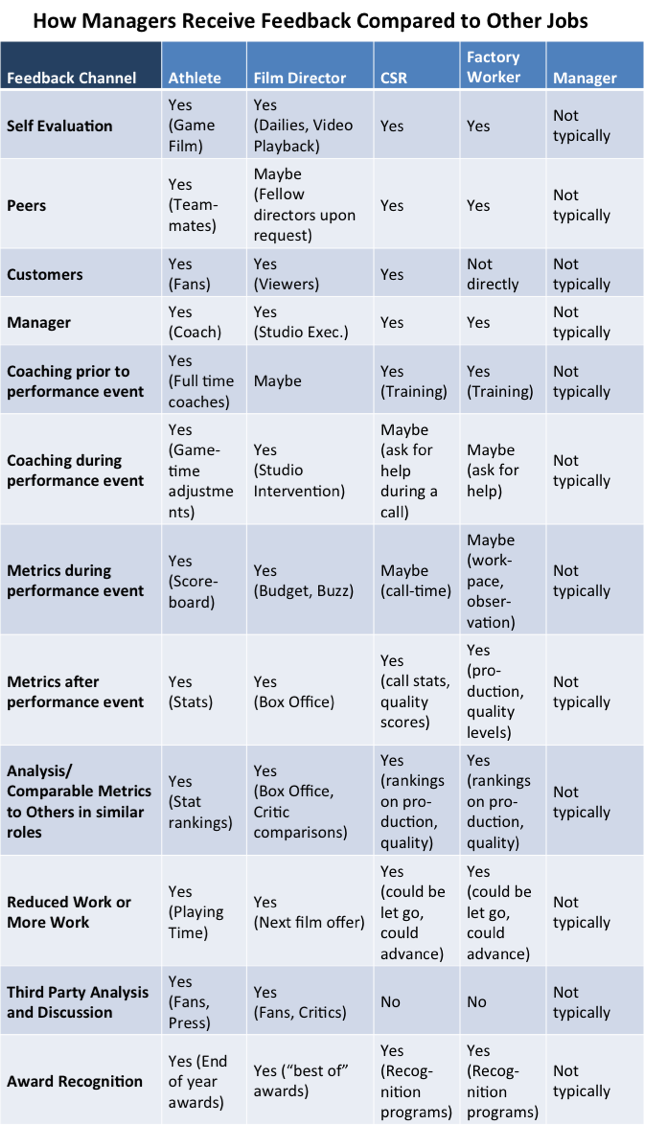

In my previous articles, I took a look at how high-profile jobs, such as athletes and movie directors, get lots of performance feedback from lots of sources. Then I looked at entry level jobs, and showed how these roles receive tons of performance feedback as well (at least this is the case in high performing organizations). These highly divergent jobs receive tons of performance feedback. Not only do these highly divergent jobs receive a lot of feedback, the quality of the feedback tends to be high, in that the performance feedback is specific and immediate, and allows the person to adjust quickly what they are doing to get better.

OK, so now let’s look at managers. The manager’s job is to manage, hence the name “manager.” So surely managers get lots of feedback, right? No.

In previous articles, I’ve discussed general sources of feedback that managers receive and how incomplete they are. Sources such as 360 degree feedback programs, employee surveys, attrition rates, they tend to be faulty as sources of performance feedback. To underscore this point, let’s compare where managers receive feedback on their job as managers to both high-profile public roles (athletes and movie directors) and entry-level positions (customer service representatives and factory workers).

For the athletes and the movie directors, there is a surplus of performance feedback, some of it sought out, and some of it unsolicited. In fact, entire third party industries have been created to develop and publish statistics and analysis of the statistics for the high profile jobs, and athletes and movie directors have a hard time avoiding this kind of information.

Entry level jobs receive a lot of performance feedback: What about managers?

The Manager by Designsm blog seeks to start a new field, “Management Design,” that takes seriously how to create great managers. In order to be great at anything, you have to receive a lot of useful performance feedback. It has to be timely and specific. It has to be actionable. It has to be ongoing. In my previous article, I looked at high-profile careers – athletes and movie directors – and identified the way they receive performance feedback.

Now let’s look at some low-profile careers and how they receive performance feedback:

Customer Service Representative:

In quality customer service organizations (they do exist—think of the ones you have had a good experience with, not the ones you dread talking to), the Customer Service Representative receives a lot of performance feedback. Here are some sample places:

–From the customer they just talked to (“Thank you for your help!” or “That won’t work for me” or “I want to talk to your manager and complain.”)

–From self (“I won’t say that again!”)

–From peers in the adjacent cubicle who overhear good or bad service (they don’t want to talk to the person calling back)

–From their manager who listens to calls and provides feedback afterward

–From a quality team that listens to calls and provides feedback afterward

–From daily and monthly statistics surrounding call time, quality scores, and other metrics

–From aggregate customer service organization statistics (customer satisfaction, average call time) and the individual comparison to the aggregate scores

–From awards, both individual and team

Note: The lower quality customer service organizations do not necessarily have these robust structures, which may explain the lower quality and frustration many people often have with customer service.