Think of managing a team as a set of deliverables

In my prior article, I describe the dynamic of promoting a top individual contributor to management as a form of reward, only for it to turn into punishment. Yet this is not inevitable. You can find top individual contributors who become top managers. After all, if your top performer was able to learn one series of complex skills as an individual contributor, it stands to reason that the top performer is able to learn a second series of complex skills as a manager.

However, what are those skills? In individual contributor roles, people are expected to deliver something, and this is what they get used to as good work: “If I produce X, at quality Y, and in time frame Z, then I’ve done a good job.”

It’s a set of deliverables that tend to be pretty well defined.

Now the individual contributor becomes a manager with a team of three. The dynamic is suddenly, “Now there is four of me, and now my team needs to produce 4x at quality Y and in time-frame Z.

What the manager needs to produce is now ambiguous: Do you help produce all that stuff? If one person on the team is a lower performer, do I have to double my efforts and produce myself the gap in productivity? Do I stop producing individual stuff and monitor the work of the lower performers, risking lowering the productivity of the team?

The natural instinct for a new manager is to keep doing the individual contributor work, and hope that others will do as well. The problem is that the management tasks become a distraction from that individual work, and you get both an unmanaged team and a distracted, formerly high performing individual contributor. It becomes a mess where formerly rational employees become yelling managers and, in general, manage from a deficit.

So here’s a way to present to the manager what they have to do in a way that makes sense to an Individual Contributor: Management is a series of deliverables. They are different deliverables from the work done as individual contributor, but deliverables specific to being a manager.

Here is a sampling of what these deliverables are:

—A team “what/how grid”

—A performance log on employees

—Team expectations for performance

–Employee performance feedback delivered and documented

–Documented efforts to improve how the team works as a team

–Documented efforts to improve how the team works with partner teams

–Efforts to improve processes and tools

Tenets of Management Design: A role in management is not an extension of performance as an individual contributor

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field I’m pioneering, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the bad existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, or that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short, often to damaging consequences. We need to turn this around.

Today’s tenet: A role in management is not an extension of performance as an individual contributor

Most people start their careers as an individual contributor (IC). They bring skills that they learned in school or at other organizations, and then develop their skills in their role as an individual contributor, both through initial training and on-the-job experience. As I’ve documented, people in individual contributor roles tend to get lots of performance feedback and guidance on how they’re doing this job. If the manager of the individual contributor is doing her job, the manager is one of the sources providing ongoing, specific and immediate feedback to the individual contributor.

If the manager is doing an even better job, she is also strategically developing the skills of the individual contributor to what the organization needs to be successful.

When this works, this is a good design!

OK, so now how do you find people in management? From individual contributors of course.

Here’s where the mistake frequently occurs:

The management team will identify individual contributors for their skills as individual contributors, and then “reward” them for their outstanding work in this area with a promotion into management. The simple theory is that if the individual contributor could do X amount of positive work as an individual contributor, with a team of say, 3 people, the individual contributor can achieve four times the amount of productivity. That is 3X with direct reports plus the X that the individual contributor could produce. On top of that, the high performing individual contributor is rewarded with a promotion to management, which is typically higher paying and has higher status.

For example, Jim is an amazing business analyst. He creates insightful reports from a series of diverse sources, they are easy to read and understand, and always seem to provide recommendations that are spot on. He also comes up with useful pivots and ratios that allow the decision-making teams to ask in-depth questions that can be answers. The management team wants more. So they promote Jim to Business Analyst Manager, and he inherits a team of three other Business Analysts (Betty, Sarah and Amari), with the idea that they can produce what Jim does on his own to 4X the amount — 80 reports — with Jim-level quality.

That’s the implied theory I’ve observed.

Strive toward strategic placement of employees based on organizational need

In my previous post, I discussed how it takes a lot to compare and stack rank employees, and really the best you can do is to come up with some limited scenarios where you compare similar jobs, with clear rules, consistent evaluators and transparency. With that done, you now have determined the winner in a limited context in a given time frame. So it doesn’t really tell you who is the “best”, but who was the best in that context. If that context comes up a lot, then you can get trends and be more predictive, such as the case in answering “who is the best athlete,” but still leaves a lot open for debate. In the contemporary workplace, these conditions happen less and less.

In the contemporary workplace, employees are asked to adapt to constantly shifting situations, new technologies, new projects, and new skill sets. Instead of who is the “best” at something, it is the who is the “best” at adapting to new situations, which can go in many different directions. You need people who are great in different facets of the work, and who can adapt and improve and strive toward meeting the organizational goals. This makes it very unlikely that you can have some sort of conclusion who is the “best” and who is “on top”, since there is a diversity of skill sets needed to achieve these goals, and they are often shifting.

So instead of “stack ranking” employees, which implies that one employee is inherently better than another (and makes a not-so-subtle argument that it is forever that way), managers need to strategically place employees in roles and projects based on what the managers and employees assess they are good at and their ability to execute. It’s less about who’s the best, and more about what is the best placement to get the work done.

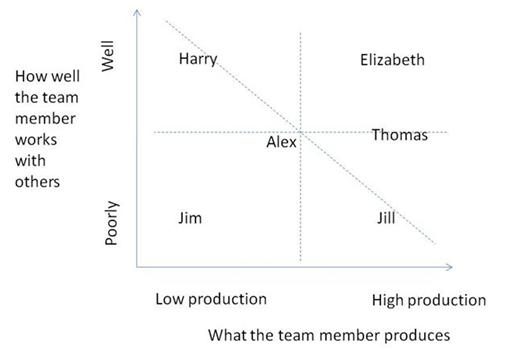

Let’s take a look at the What/How grid to be as a way to be more strategic with a team’s strengths. This grid shows an analysis by a manager of a fictional team, based on “what” the team member produces and “how” they work with others. Other analyses could be performed based on your organizational needs.

In this grid, the manager has assessed that Elizabeth and Thomas as skilled in both productivity and ability to work with others. But the manager also has Harry who seems to get along with lots of people, but doesn’t produce much, and Jill who seems to work really hard but isn’t as focused on relationships. So now the manager, instead of saying, “Elizabeth and Thomas are my top performers”, the manager should say, “What can I do with this group to get the most out of my team?”

I’d put Harry in a role that requires relationships to be forged. I’d make sure I’d give Harry some expectations for what we are looking to get out of those relationships (new leads? sales? higher customer satisfaction? socializing a new program across groups?) and rate him against these expectations. I’d put Jill in a role that is not customer-facing but requires a lot of work output where relationships are less crucial for success, and rate her against what she produces (and diminishing the importance of “how” she produces). Ideally, this most likely feeds to Harry information that makes him better. If I need more customer-facing work and relationship building, I’d put Elizabeth on that, and if I need more work output, I’d put Thomas and Elizabeth at that.

Elizabeth and Thomas are more flexible, which obviously has value, but if the value of customer relationship building is super-important for the team, then perhaps Harry is more valuable than Thomas for now. It isn’t a permanent thing, but a thing that is based on the context of the team’s needs, and not on the context of the employees inherent abilities.

With Alex, I would try to figure out where Alex is most likely to be needed in the near future, and work on giving performance feedback and coaching in the direction where your team is likely to need it. Perhaps Alex can be a back-up to Harry in the follow-up with customers.

With Jim, he rates lowly in two dimensions, which looks like a net-negative to the team, so I would look at the performance management process for him, because it doesn’t look like he’s helping the team at all, and unless he improves (which is entirely possible with the performance management process) there is likely someone else out there who could do his job better.

So instead of saying, “Elizabeth and Thomas” are the most important employees, the manager should first focus on trying to maximize where all employees can most help the team to achieve its goals. This treats all employees as valuable, and is likelier to achieve overall team performance.

This is where the management energy should be spent first and foremost. The shifting dynamics of the team context should be the greater concern, not the ranking of individual employees against one another, since you need the entire team to perform to be successful.

Also note that once placed on this grid, the people are not permanently located there. Any one of them can shift around based on changing circumstances, work stresses and pressures, and individual development.

In this article, I use a very simple “What/How” grid to identify the strengths of the team and to assist with illustrating how a manager can use this simple tool. Another common method is to use the Strength Finder tool from the book Now, Discover Your Strengths, which has many more dimensions and areas of insights and one I would highly recommend any manager do to identify the areas of strengths on the team and then make strategic decisions accordingly.

How much energy does your management team spend in strategically utilizing employee strengths? How does this compare to the amount of time ranking employees?

Related Articles:

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

An obsession with talent could be a sign of a lack of obsession with the system

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

How to use the What-How grid to build team strength, strategy and performance

If you really want to evaluate performance across individuals, here are some things that need to be in place

In my previous article, I discussed how many organizations spend time identifying who the top performers and stack ranking employees, to the detriment of assessing other areas that drive performance. Management teams obsess on determining the best performers are. Once done, this implies you now have what it takes to get ahead in business. It’s an annual rite. Despite this process causing lots of angst, the appearance of accuracy in the face of tertiary impressions, and the general lack of results and perhaps damage it causes, this activity continues to have a high priority for many organizations.

OK, so if you really want to do it – you really want to compare employees — here are some things that have to be in place if you don’t want to cause so much damage and angst in the process:

1. You can compare people only across very similar jobs

Many organizations attempt to compare people across the organization, in kind of similar jobs, and under different managers. Then they try to assess the value of the various outputs of the jobs that had different inputs and outputs. If there were different projects and different pressures, different customers and different challenges, then it will be difficult to say who is the better performer.

An obsession with talent could be a sign of a lack of obsession with the system

Malcolm Gladwell wrote an excellent article called “The Talent Myth”, which appears in his book What the Dog Saw. In this article, he discusses companies that obsess over getting the top talent and the consequences of this. He focuses on Enron, and how it sought obsessively to attract and promote those with the most talent, which, amongst other things, resulted in a high degree of turnover within the company and made it difficult to figure out who actually was the best talent. In the article he asks:

“How do you evaluate someone’s performance in a system where no one is in a job long enough to allow such evaluation? The answer is that you end up doing performance evaluations that aren’t based on performance.” (What the Dog Saw, p. 363)

Does this describe your organization?

I’ve recently written about how many organizations go through a painful, angst-ridden and rhetorically charged process of identifying who the top performers are in an organization. Different managers assert their cases and advance some employees as “high potentials” and others as “needs improvement.”

This effort inures the concept that there is some sort of truth about an individual performer in comparison to her peers, and that this is relationship is static. Or, when it comes to annual reviews, true for at least one more year.

The process of deciding who’s on top and who needs improvement is an ongoing assertion that talent is the most important thing. If you can get more talented people, the more successful you will be. That is the thesis that this activity of ranking employees seems to advance.

But as Malcolm Gladwell’s article shows, this isn’t such a great idea, and it’s a weak thesis at best. There really is no way to judge performance in a highly evolving situation, and the judgment quickly moves from who has the most talent to who appears to have the most talent or who claims to have the most talent. As I showed in my article On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees, such decisions are usually made by tertiary impressions rather than a first hand examination of performance.

It’s a management short cut – the notion that if we have the top people, then everything will just fall into place. But for some reason, this rarely seems to work out.