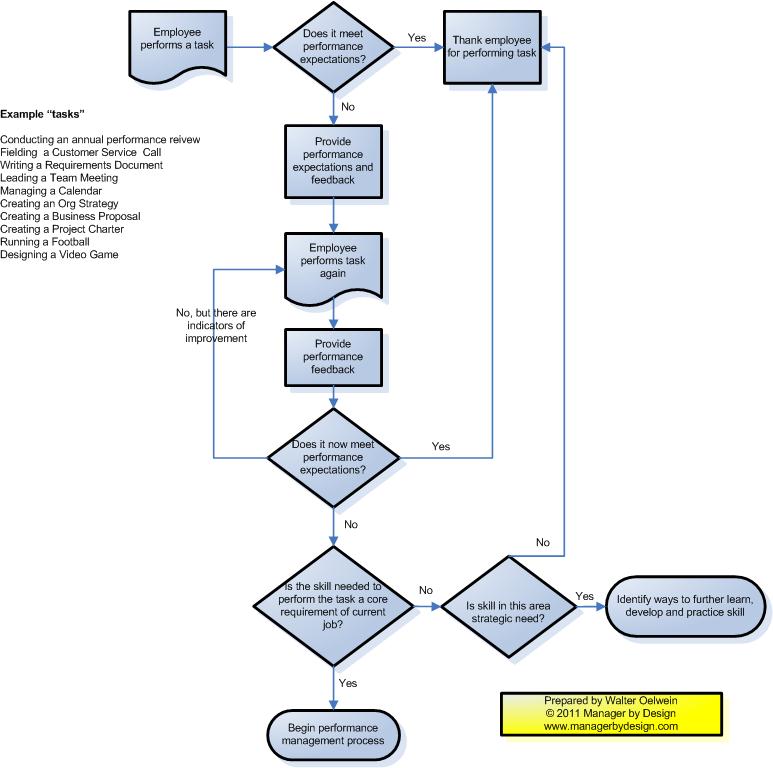

A Performance Feedback/Performance Management Flowchart

The Manager by Designsm blog seeks to create better managers by design. Here’s a great tool that outlines a simple flowchart of when a manager should provide performance feedback, and when the performance management process should occur. It can be used in many contexts, and provides a simple outline of what a manger’s role is in providing feedback, and how this fits with the performance management process (click for a larger image).

You’ll see that Performance Feedback starts at the task level, not the person level. You want to know what the task is, and make sure the individual gets feedback on how well he or she is performing the task. It also requires the manager to know what acceptable performance looks like. If not, then the manager is in a complex feedback situation, and both the manager and the employee agree to strategize on how to do the task differently, since it isn’t defined yet.

You’ll also notice that there is a lot of activity prior to the performance management process, which is actually a more formal version of this same flowchart. Managers need to perform this informal version first.

Let me know what you think. Do you your managers follow this flow chart? Do they skip steps? Do they add steps?

Related articles:

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

How to have a feedback conversation with an employee when the situation is complex

A tool to analyze the greater forces driving your employee’s performance

When an employee does something wrong, it’s not always about the person. It’s about the system, too.

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

What inputs should a manager provide performance feedback on?

When to provide performance feedback using direct observation: Practice sessions

When to provide performance feedback using direct observation: On the job

Annual reviews are awesome artifacts that can be used to improve management skills

The Manager by Designsm blog has documented many issues that annual performance reviews bring to the manager/employee relationship. I’ve written about how they are “toxic”, cause angst, and perpetuate myths both about employee capability and what acceptable management practices are.

But I’m not totally against annual performance reviews. Sure, I don’t think that they are effective at actually evaluating performance of the people they are evaluating, but I do think that they are extremely effective at revealing the practices of the managers conducting the reviews. They are a treasure of information that provides a window into how the manager relates to her employees, how she assesses performance, and the degree of effort taken to help the employees improve.

So I say keep the performance reviews, because this is the only infrastructure – however flimsy (I can’t elevate it to the level of “design”) — that many organizations have that actually require managers to perform management-related tasks, such as setting expectations and goals, assessing and discussing performance of the employees, and actually committing this to a document that demonstrates that this task has been performed.

Five more markers and examples of what a good annual review looks like

In my previous article, I provided five markers of what a well-conducted annual review looks like. Let’s look at some more. It is possible to actually conduct an annual review well, but this is no guarantee. So let’s keep looking for those precious markers of a manager who knows how to use the annual review for good, rather than perpetuate it as a tool for suffering.

Marker #6: Improvement is germane to the discussion

If the annual review has any discussion about where the employee’s skills and performance was at the beginning of the year, and a comparative analysis at the end of the year – in those same skills – then this means that the manager is actually concerned with increasing the capability of the organization. I would consider this generally a good thing. For example:

“At the beginning of the year, we discussed how we can improve Alex’s presentation skills, as she frequently presents business partners. During the year Alex sought mentoring and feedback in this area, and the results show that this effort has paid off. Our partners have reported that they find her speaking style inviting and informative, and Alex has consistently been able to meet the objectives of the presentations.”

Marker #7: References to the goals

First, a marker would be that the employee and the team actually have some sort of goals. That would be the first marker of a good performance evaluation, as it provides something against which the manager evaluates the employee. Now, the second part of this is if the manager actually references the goals in making the evaluation.

“We had the ambitious goal at the beginning of the year to implement a new payroll system to further streamline what was before a highly labor-intensive project. Jeanine was a key part of the team that scoped the project, identified the goals of what success of the project was. Jeanine managed the vendor selection process, kept the team focused on the desired outcomes, and ensured that the team understood what was in scope and out of scope via her weekly communications. This was a key factor in assuring that the project stayed on track, which it did. The new payroll system was launched on time earlier this year, and has significantly reduced the processing time.”

Marker #8: Teamwork is referenced by both the employee and the manager

The individual performance review necessarily focuses on the individual. I consider this bad management design, as individual work is good, but teamwork can create greater outcomes. Almost all workgroups rely on teamwork. Managers and employees can transcend the design by invoking what teamwork happened during the review period. Let’s say that the manager talks about the great teamwork that the employee engaged in. Let’s say that the employee mentions how she contributed to building the team, and how she made an effort to improve the capability of the team, or looked out for the interest in the team. This would reflect that the manager and team are actually concerned with the power of teamwork over the expectation for an individual to perform independently of teamwork. Here’s an example:

“Jonathan demonstrated that he is an excellent team player by creating a process document that showed how to complete a task that many team members performed irregularly. This helped the team gain some efficiencies, and inspired other team members to make similar efforts. The team is healthier as a result of Jonathan’s efforts.”

Marker #9: Goals seem to have a similar voice and scope across team members

Many annual reviews have a section where the employee’s goals are documented. One could look at the goals of all the team members across a managers’ team. Imagine, if you will, goals that seem to have a similar tone, similar metrics, and similar scope across team members. They don’t have to be exactly the same, because not all roles are the same, but if the goals are all striving toward a similar metric or output, this demonstrates that the manager knows what the team is striving to do, and has actually infused it in the goals. When the goals seem to be similarly written, we also know that the manager has provided input and perhaps even co-authored the goals – or this is sometimes tough to imaging – this was done as a group. Too many times we see managers push down the goal writing process to the individual employees, which results in, by definition, different looking goals. Let’s celebrate those times when we see goals across the team show some kind of consistency across the team.

Marker #10: There is agreement between the employee and the manager

If a manager and employee seem to say that they agree about things on the performance review, this reveals that the employee and the manager actually talked about these things prior to the annual review. Differences in what the results were, what the impact of the employee’s actions and whether or not the employee performed at a high level – well these were resolved external to the review, as should be the case. Many managers wait until the review to resolve lingering disagreements, sometimes even using the review to create new ones, but those managers who seek alignment and understanding with their employees throughout the year, and don’t wait until the end of the year should be recognized as superior managers. Here’s what alignment looks like:

Employee: “I increased sales by 15% through my efforts to reach out to a new customer base.”

Manager: “I agree with the employee. He was effective at identifying a new target market, and then executing the strategy of accessing the market.”

See? no debate! Do you think that a debate might have happened during the year to get to this agreement of what the employee’s efforts were and what were the estimated results? Yes. Does it appear on the annual review? No, but the agreement of the results of the discussions do appear.

We should celebrate when managers do a great job on the perilous annual performance review, and do whatever we can to increase the chances of a well-conducted review.

Have you seen these markers of success on a review? Let’s hear your stories!

Related Articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

How to neutralize in advance the annual toxic performance review

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review