Tenets of Management Design: Drive towards understanding reality and away from relying on perceptions

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field I’m pioneering, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the bad existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, and that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

Today’s tenet of Management Design: Encourage reality over perception

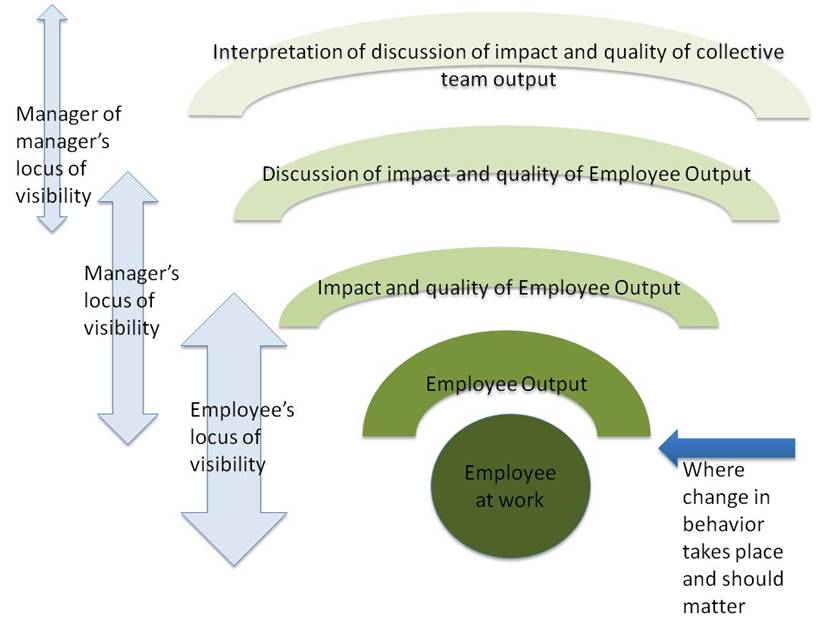

In a previous post, I describe a common situation where employees are evaluated, spliced, diced and put into categories to determine if they need improvement, are high performers, or are in that special purgatory of the middle. The problem with this process is that it requires decisions based on perceptions or, worse, perceptions of perceptions, or perceptions of perceptions of perceptions. This is shown in the “meta slide” of evaluating an employee’s contribution.

This is bad management design. In such a design, managers and managers of managers are charged with the role of doing (what I call) phantom managing — ranking employees — based on argument, rhetoric and perception. Typically, each manager is allowed to bring in their own methods for advocating (or denouncing) their employees, and argues accordingly. This is in the spirit of creating a truth about the employee: Where they fit in the “stack rank,” whether they are “needs improvement” or whether they are “high potential”. The design is, in effect, to create that impression, to create that tag and, for all intents and purposes, institutionalize the worth of the employee as either low, medium or high based on a team of managers’ rhetoric.

Here are some outcomes of this that make this bad, degenerative management design:

- This kind of situation institutionalizes perceptions as the dominant formula for evaluating and tagging employees

- This places an emphasis on evaluation of employees as more important than working with employees to perform at an acceptable level.

- This puts the onus away from the manager and assumes the employee is solely responsible for success in a role

These three outcomes place at a premium the perception of an employee (and what the employee and manager do to manage perceptions), rather than place the focus and emphasis on the reality of the employee’s work output and behaviors.

So instead of focusing on the perceptions, let’s focus on some realities of employee performance:

First, the reality is that no employee can possibly be permanently categorized as low, medium or high. Things are too dynamic – in one situation an employee is great, and in another situation an employee is terrible. Too many times we have observed employees do badly in one context and do great in another (see my article about how to evaluate the system as a part of performance feedback). Does that make the employee good or bad? It’s neither. Putting a tag that risks being a permanent tag creates an unnecessary perceptual problem about the quality of the employee. In addition, that tag, with its trace perception, is likely to carry over year over year.

Next, the reality is that a manager’s role is to do what it takes to make sure the team performs as at high of a level as possible, using the available components of the team, tools, processes and work environment. This evaluative process of tagging employees in one category or another in effect removes that burden from the manager, and creates the perception that the employee capability is the number one factor of team (and manager’s) success, and the rest is out of the manager’s hands. The manager can say, “Well, I have two low performers on my team, thus we couldn’t get it done.” The manager’s real job is not to put those low performers in the low performance bucket, but to figure out how those low performers can contribute to the team to make the team effective. If those low performers are that bad, are a terrible fit, and shouldn’t even be on the team, there is the option of performance managing the low performer. Instead, too many managers wait until the end of the year, exact their revenge on the low performers by saying, “Well, they are low performers!” And sure enough, that low performer appears the following year as a low performer. The manager’s role? Declaring them as low performers.

Third, the reality is that the manager has a huge impact on the individual contributor’s performance, perhaps as much as the individual contributor has on his performance. The manager who sets up expectations well, who assures that there are processes that drive a consistent strategy, who discourages drama and who encourages teamwork will make any set of employees better. These are managers who can turn a team of average performers into a team of star performers (who then get tagged as “high potential” – until those high potentials go into a broken system, then lo and behold they become low performers). Obviously the individual contributors need to bring their “A” game to make a truly high performing team, but with current management design, there is an assumption that every team needs to be filled entirely with Michael Jordans and Zinedine Zidanes to be successful. Simply not the case, as even Messrs. Jordan and Zidane, with all of their success, never had such teams.

Drive the focus toward the reality of an employee’s output

So instead of engaging in meta-perceptual conversations about the relative worth of each employee, good management design should discourage structures that solidify perceptions, and push the manager to the reality of creating as strong a team as possible, focusing on the behaviors of each team member, and getting as close as possible to the reality of the team performance.

The dark green circle is the closest we can get to understanding reality. In good management design, the focus should be that managers think and deal with the employee at work, and try to get the behaviors to the maximum effectives, both as an individual and as a team. The manager still has a few degrees of separation from direct understanding of the reality of the employee’s work, but instead of encouraging moving further away from it, good management design should encourage getting closer to it.

In current management design, the default situation is to start to evaluate an employee based on the outer “waves of perception” that emanate from the employees’ work output. The “waves” of perception then go up the management chain, and an evaluation of the employee happens based on meta-interpretations of the employee.

In many organizations, more politics, more angst, and more discussion about the outer rings of perception are generated, rather than about the reality of what the employee actually does at work. As a result, both employees and managers spend crazy amounts of time managing these perceptions, and in some cases, almost abandon entirely the actual work that needs to be done, confusing the need to manage perception with actual work.

So today’s management design tenet: Design management systems to focus on actual behaviors, rather than encouraging them wallow in the waves of perception.

Does your organization seem to have a lot of politics? Is the focus of an employee based on what is actually done, or the various perceptions of people, and the accompanying political jockeying?

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

Tenets of Management Design: Focus on the basics, then move to style points

Tenets of Management Design: Managing is a functional skill

The problem you point out here is very true.

Because the role of the team and team management is so crucial, I think that evaluating team net performance is much more important than individual assessment.

Too much individual assessment is tied to the concept that most income is tied to salary. There is a great deal riding on how to divvy budgets among a group. If teams and individuals were incentivized by bonuses and rewards tied to actual accomplishments as they occurred, the focus would shift.

Assessments should be forward looking — If you accomplish this, I will give you this — and not backward looking.

Thanks for the great comment, Jane! I like your call-out of forward thinking vs. backward viewing, as the backward-viewing encourages creating perceptions vs. understanding the actual work that needed to be done.