Management Design: The Designs we have now: The paths to management and leadership

This continues a series of articles that examines the differentiation between management and leadership by looking at a model I created that specifies the difference between management and leadership:

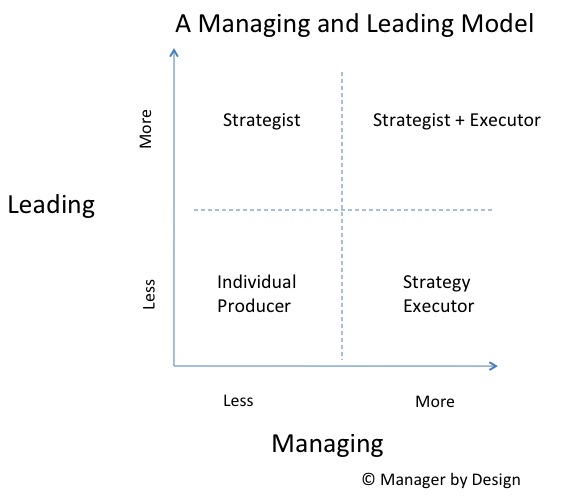

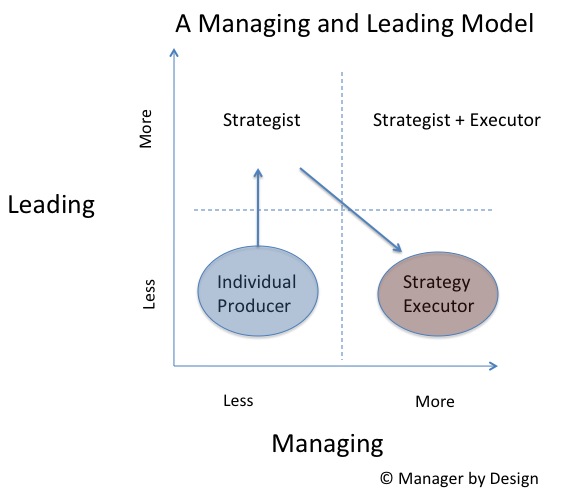

In this model, I make the point that it is possible to be a leader without being a manager, and a manager without being a leader. The main differentiation is the action of setting strategy and the action of executing the strategy.

At the same time, we normally conflate leadership with doing both strategy and execution. In my model, that is fine, but the leadership element is still tied to strategy and the management element is still tied to execution. If you want people in your organization to be both strategists and executors of strategy, then this model is useful.

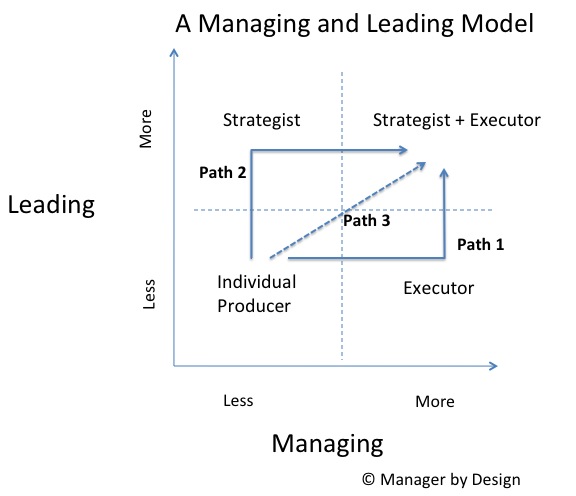

So let’s look at how that can be. Here are the three paths that are typically considered how someone becomes a do-it-all leader/manager (or, in my model, a strategist + executor).

Path 1: Become a manager, then start doing strategy

In this path, someone becomes a manager of a team they probably served on. They are charged with keeping an existing strategy going, and making sure that team has the existing level of productivity. At a certain point, that manager steps out of that role and starts coming up with new strategies and direction for the organization, while continuing to be a manager of a team or organization.

Current management design: The one with the ideas becomes the manager

In my previous articles, I showed why managers are often resistant to change or are bad at leadership – by design. In today’s article, I’d like to walk through another common scenario – the leader who then has to manage.

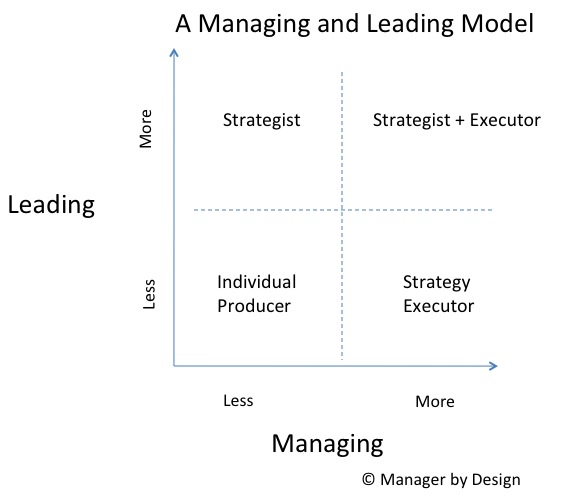

I’ve created a model that shows the difference between leadership and management.

In this model, it allows for an individual person without a team to demonstrate leadership. If they are involved with setting the strategy for an organization, they are a leader. Oftentimes this is the person with the idea, and that person does a lot of work to spread the idea, get support for the idea, and convince other parts of leadership and individual producers of the need to pursue the idea. If that idea actually gets executed, it sure looks like that person is a leader – the person leads by being out in front of an idea, and leads by making sure the idea got into the hands of those who can do something about it.

So that shows how someone can become a leader without managing a team!

I love this scenario, because it shows that someone in an individual contributor role can be considered a serious leader in an organization. There are many people like that in an organization, and this kind of path to be a “strategist” shows career growth that can provide terrific value to the organization. It also shows that the strategist does not have to be the strategy executor (a.k.a., manager) to be a leader in an organization.

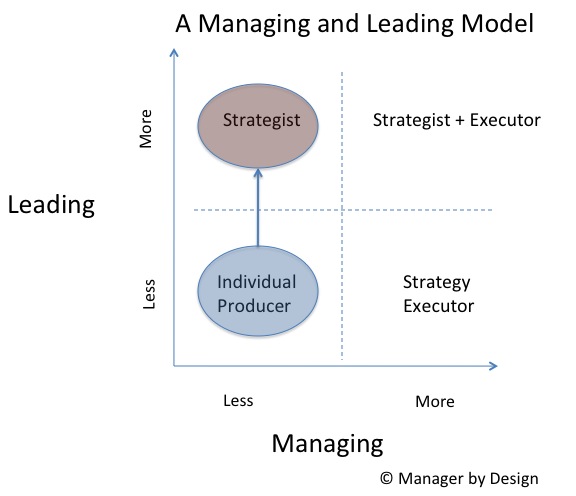

Now, here’s the problem. Many times organizations say, “This is a great leader!” Then they put that person in a manager role:

We’ve seen this frequently in organizations. When someone shows leadership, they are given a team to execute that strategy. It is a common marker of success for that individual. Here’s your team – now go do it!

A common identity of a manager is the ability to rise in the organization – and is this a good thing?

I’ve recently been writing about how the act of becoming a manager is an act that destroys the personal work identity of that new manager. The manager no longer gets to do what they were good at as an individual contributor (IC), and now they are doing something they are new at – and perhaps in an awkward and amateurish way. So the identity of being good at the former job is lost, and the ability to do the new job of management is slow to develop – if ever.

However, there is one aspect the new manager’s identity that is quickly formed via the act of becoming a manager. That is: The ability to “rise” through the ranks.

This is a differentiation that the others individual contributors (IC) in the organization do not have. Only the manager has demonstrated this “skill.” So while the new manager may lose his ability to perform the IC job, is no longer an expert at the IC job, and suffers through suddenly being amateurish at his job, the manager is indisputably good at one thing: Getting promoted into the manager ranks.

Why managers don’t give performance feedback – it hurts the ego

I’ve recently taken a philosophical turn in the Manager by Designsm blog. I’ve been drawing from Lacanian psychoanalysis to explore the concept of a manager ego. The short version is this:

- Managers lose their identities when they become managers

- However, they became managers based on their ability and expertise, which is their former identity

- They can no longer perform those former actions, and must perform new managerial actions

- These managerial actions, while based on the notion of personal greatness, are, by definition, new the manager and amateurishly performed.

- The first time such an amateurish action (like giving performance feedback to an employee) is performed, it shatters the notion that the manager is expert, effective and useful.

This step 5 I’m calling the “Mirror Stage” of being a manager. It’s the moment that, despite all sorts of evidence that the manager is terrific (hence the promotion to manager), there is the stunning evidence that the manager’s management technique is ineffective.

Here’s a likely – and concrete – scenario: A manager has to give performance feedback to the employee. The manager goes in with the expectation that the employee will agree, understand and implement everything the manager says. But this is nigh impossible. The employee could provide his own, different perspective on the situation, may not understand what the manager is trying to get across, or may not implement exactly what the manager had in mind. And that’s when an employee reacts well to the feedback!

What if the employee actively resists the feedback? The employee argues with the manager, says the facts are incorrect, and even says that the manager is wrong. There may even be an emotional reaction on the part of the employee. This is shattering to the manager’s ego, because this simple act of giving performance feedback didn’t go well (in the managers’ mind), despite the manager having a) authority b) expertise c) a greater general talent level than the employee.

In short, the act of giving performance feedback breaks the ego of the manager and provides a rather sudden and obvious moment where it is indisputably proven that the manager is not 100% effective at managing. So now there is now a problem associated with the act of managing.

Giving performance feedback breaks the illusion of greatness of a manager

For this article, I’d like to draw upon a concept created by Henri Wallon and popularized by French structuralist philosopher and psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. The concept is the stade du miroir, or “the mirror stage.” The mirror stage is when an infant first sees himself in the mirror and, by virtue of seeing an image of himself, understands for the first time that he is not an embodiment of the entire universe but is instead that he is a single individual amongst many others. In short, the infant goes from thinking he’s everything to only one thing, goes from not having an identity to having an identity, and from no external image to an image of himself external to himself, and has for the first time an understanding of the other. The scope of the infant’s identity has gone from huge (or unlimited) to that of an image of himself.

OK – but this is a blog about management skills – what does this have to do with managing?

I would like to propose that – for a manager — the act of giving performance feedback is the equivalent of the mirror stage.

I have recently written about how a new manager has been stripped of her identity the moment she becomes a manager, and how that identity is often then built up using management techniques derived from individual instincts for what good techniques are. As a result, many managers persist in a kind of ongoing limbo of amateurish techniques while trying to retain the aura of expertise that they once – but no longer – have. That manager is in the difficult position of asserting that she is expert in the domain they were a former individual contributor (IC) while simultaneously asserting that she is an expert in the managerial tasks related to overseeing that IC work.

Now, imagine a manager who never gives performance feedback to the employee. That manager is like an infant who has never seen his image in the mirror. That manager can continue to think that she is

a) Expert in the field she is managing

b) Knows more than her employees

c) She can convey what is the correct way to proceed without much effort

d) Her employees believe in 100% what she says

e) Her employee can immediately implement what she has in mind

Does this sound like any managers you know or have had in the past? This manager has not gone through the “Mirror Stage” of being a manager and confronted their limitations as a manager.

Now, imagine a manager who decides to give performance feedback to the employee.

This is the moment where the manager must test the following notions:

a) she is still an expert

b) knows more than her employee

c) the conveyance of her thoughts are 100% transmittable

d) the employee will accept 100% of what she says

e) the employee will immediately implement what was in her thoughts.

That is the way an infant thinks before the mirror stage. Read more

The new manager is an amateur at doing managerial tasks

Perhaps this is obvious, but has it ever occurred to you that a new manager is actually an amateur at being a manager? Not just initially, but ongoing, well after becoming a manager? Let me explain.

The typical model is that someone starts their career not as being a manager, and then, after a certain moment in time, becomes a manager. It’s a new job title, new role, and lots of new stuff to do. And this new stuff – since it is new, shouldn’t we expect managers to be amateurish in how they perform these tasks? After all, they have never done this professionally before.

Perhaps this moment of becoming a manager isn’t entirely ignored, as there are many management development programs out there, but even with this assistance and turbo-boost into management ranks, there is a reigning operating theory – that when you hire people who are generally competent in their field, they will perform this new complex job of management competently as well.

With non-managerial roles, there is a gradual build up of skills, expertise, and speed that can possibly turn into creativity and innovation. This can be done in a short period of time, but it is generally understood that when you are starting out, you need to get better at what you are doing, and most organizations provide that chance.

Without management design, the new manager relies on base instincts

In my previous article, I discussed how the moment an employee becomes a manager, her identity – in so many ways – is entirely subverted, and this loss has both an immediate and long-term impact on how the manager performs as a manager. Does the manager keep trying to develop expertise and perform the tasks in the field she is managing? That doesn’t make sense, as the manager isn’t actually doing the task. Does the manager rate herself using the same metrics and peer groups as before? No, that’s difficult because there is a team element and because team output is difficult to compare. Does the manager still identify herself with the trade she’s managing? No, because she isn’t doing that trade any more.

But perhaps the biggest sense of loss when someone becomes a manager is simply not knowing what to do.

Before becoming a manager, there was a schedule, inputs, outputs, a work stream, and some sort of set of measurements that determined quality and quantity. It was very likely that these things were defined by someone else long before her arrival, and in the case of trades, these techniques and expertise have been built up and modified over decades.

Now, when it comes to management, is there any such regiment that organizations provide? Sure there might be a lot of tasks that a manager is supposed to do – approve time cards, monitor attendance, host a team meeting, answer questions over email. These things come to mind. But after that – where does a manager start?

OK, so maybe the manager starts a new series of things – sets up one-on-one meetings, sets up meetings with other managers, sets up meetings with the new manager.

Now things start getting a little more abstract – now what? Does the manager start looking at work output of the team? Does the manager try to gather or look at metrics of team output? Are these things even available?

When does the manager actually start managing? Is it the first moment of providing performance feedback? Is it the moment the manager leads a team meeting? Is it the moment the manager creates a team vision or strategy (and does it have to come directly from the manager)? Is it the moment the manager sets expectations for how the team performs?

Becoming a manager is a subversion of self-identity

Let’s talk about the manager and his or her identity at work.

The act of becoming a manager is the very act of undermining the person’s identity at work. Here’s why:

For years the employee who was not a manager has the following elements associated with the employee’s identity:

–What you do at work is produce something

–Work is rated by quality and quantity metrics

–Work can be compared against other people doing comparable work

–Work quality and quantity can be improved and new techniques learned by meeting with and learning from others who do comparable work

–Expertise is increased over time

–There is a trade name/professional identity associated with the job (mechanic, accountant, camera operator, software engineer, etc.)

With these fairly well-defined elements that contribute to the identity of the employee, the employee can develop a general understanding of who she is and what value she provides. On top of that, she can see fairly easily how she performs in comparison to her peers, and she has peers to which she can compare and learn from. Via this identity, the employee develops a sense of who she is and what she is capable of, and where she fits in the organization and the industry.

Then the moment she becomes a manager, all of this is lost. It is taken away. It is eliminated. It is killed off. The employee has lost her identity entirely. Let me explain:

Element #1: The loss of productivity

The moment the employee becomes the manager, she is no longer expected to produce something. Sure she is in charge of the people who produce something, but she herself does not produce anything any more. In fact, the manager who attempts to keep producing something to keep this element of her identity becomes something of a ghost of an employee – someone who neither produces as much as the others nor manages the team very well. That sense of productivity is gone.

Element #2: The abstraction of quality and quantity metrics

The employee who becomes a manager no longer can produce quality and quantity, but must indirectly produce quality and quantity from the other employees. It used to be a direct creation of what is productive, but now it is an indirect, abstracted creation. The manager has lost the direct sense of what productivity looks like, and now has only a trace of that sense of productivity. It is an abstract concept rather than a concrete concept. Any former claims of productivity, innovation, and quality are immediately vanquished and lost over time, and cannot be used as a measure of success in the new role.

An obsession with talent could be a sign of a lack of obsession with the system

Malcolm Gladwell wrote an excellent article called “The Talent Myth”, which appears in his book What the Dog Saw. In this article, he discusses companies that obsess over getting the top talent and the consequences of this. He focuses on Enron, and how it sought obsessively to attract and promote those with the most talent, which, amongst other things, resulted in a high degree of turnover within the company and made it difficult to figure out who actually was the best talent. In the article he asks:

“How do you evaluate someone’s performance in a system where no one is in a job long enough to allow such evaluation? The answer is that you end up doing performance evaluations that aren’t based on performance.” (What the Dog Saw, p. 363)

Does this describe your organization?

I’ve recently written about how many organizations go through a painful, angst-ridden and rhetorically charged process of identifying who the top performers are in an organization. Different managers assert their cases and advance some employees as “high potentials” and others as “needs improvement.”

This effort inures the concept that there is some sort of truth about an individual performer in comparison to her peers, and that this is relationship is static. Or, when it comes to annual reviews, true for at least one more year.

The process of deciding who’s on top and who needs improvement is an ongoing assertion that talent is the most important thing. If you can get more talented people, the more successful you will be. That is the thesis that this activity of ranking employees seems to advance.

But as Malcolm Gladwell’s article shows, this isn’t such a great idea, and it’s a weak thesis at best. There really is no way to judge performance in a highly evolving situation, and the judgment quickly moves from who has the most talent to who appears to have the most talent or who claims to have the most talent. As I showed in my article On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees, such decisions are usually made by tertiary impressions rather than a first hand examination of performance.

It’s a management short cut – the notion that if we have the top people, then everything will just fall into place. But for some reason, this rarely seems to work out.

More reasons the big boss’s feedback on an employee is useless

Perhaps I’m obsessing about this scenario too much, but I just can’t get out of my head the damage that managers of managers cause when they start assessing employees not directly reporting to them. I call this “tagging” an employee.

In a previous post, I describe the moment where a “big boss” (the employee’s manager’s manager) meets with an employee (or even just hears something about an employee or sees a snapshot of the employee’s work) and provides an assessment of the employee. “That employee really knows what she’s doing!” “That employee doesn’t seem to have his head in it.”

The problem? There are many:

–It rates the employee on behaviors not directly related to doing the job, but it’s based on an abstracted conversation about the work or a limited impression of the employee.

–It puts the manager in the middle in a situation where it would seem appropriate to correct the employee, even when it is inappropriate.

I describe what the manager ought to do about this here. But I’m still obsessed with the peculiar angst that this kind of indirect feedback will create in the employee – even when the “feedback” is good. So before I dive into my obsession, my advice to the managers of managers out there: Don’t provide assessments on an employee. Keep it to yourself. If you are really into assessing an employee’s value, you have to do the work of direct observation of work performance.

Now, let’s look at this “feedback” from the employee’s perspective and the damage it causes in an organization:

When a big boss starts trying to identify the top performers and the bottom performers based on their limited interactions, here is a survey of the damage it causes:

Makes employees one-dimensional: The employee immediately transforms from a multi-talented, hard-working, problem-solving contributor to whatever the “tag” is. This is bad even if the tag is good! If the tag is “hard working”, it diminishes the problem-solving, multi-talented part. It also creates a cloud around what the employee does the whole time at work, and instead puts a simplistic view of the employee’s value.

Assumes that the employee is like that all the time: Similarly, if the employee does a particular thing that gets the big boss’s notice, then that is the thing that the employee has to live up to or live down. For example, if the employee does a great presentation, that is what the employee is seen as being good at – the presentation, and the employee is expected to be presenting all the time to have value. There’s no visibility into the teamwork, project management, collaboration, technical insights, or creativity that went into the presentation. Just the presentation. Then if the person is not presenting all the time, then perhaps they are slacking off? That’s what the big boss might think!