Think of managing a team as a set of deliverables

In my prior article, I describe the dynamic of promoting a top individual contributor to management as a form of reward, only for it to turn into punishment. Yet this is not inevitable. You can find top individual contributors who become top managers. After all, if your top performer was able to learn one series of complex skills as an individual contributor, it stands to reason that the top performer is able to learn a second series of complex skills as a manager.

However, what are those skills? In individual contributor roles, people are expected to deliver something, and this is what they get used to as good work: “If I produce X, at quality Y, and in time frame Z, then I’ve done a good job.”

It’s a set of deliverables that tend to be pretty well defined.

Now the individual contributor becomes a manager with a team of three. The dynamic is suddenly, “Now there is four of me, and now my team needs to produce 4x at quality Y and in time-frame Z.

What the manager needs to produce is now ambiguous: Do you help produce all that stuff? If one person on the team is a lower performer, do I have to double my efforts and produce myself the gap in productivity? Do I stop producing individual stuff and monitor the work of the lower performers, risking lowering the productivity of the team?

The natural instinct for a new manager is to keep doing the individual contributor work, and hope that others will do as well. The problem is that the management tasks become a distraction from that individual work, and you get both an unmanaged team and a distracted, formerly high performing individual contributor. It becomes a mess where formerly rational employees become yelling managers and, in general, manage from a deficit.

So here’s a way to present to the manager what they have to do in a way that makes sense to an Individual Contributor: Management is a series of deliverables. They are different deliverables from the work done as individual contributor, but deliverables specific to being a manager.

Here is a sampling of what these deliverables are:

—A team “what/how grid”

—A performance log on employees

—Team expectations for performance

–Employee performance feedback delivered and documented

–Documented efforts to improve how the team works as a team

–Documented efforts to improve how the team works with partner teams

–Efforts to improve processes and tools

Strive toward strategic placement of employees based on organizational need

In my previous post, I discussed how it takes a lot to compare and stack rank employees, and really the best you can do is to come up with some limited scenarios where you compare similar jobs, with clear rules, consistent evaluators and transparency. With that done, you now have determined the winner in a limited context in a given time frame. So it doesn’t really tell you who is the “best”, but who was the best in that context. If that context comes up a lot, then you can get trends and be more predictive, such as the case in answering “who is the best athlete,” but still leaves a lot open for debate. In the contemporary workplace, these conditions happen less and less.

In the contemporary workplace, employees are asked to adapt to constantly shifting situations, new technologies, new projects, and new skill sets. Instead of who is the “best” at something, it is the who is the “best” at adapting to new situations, which can go in many different directions. You need people who are great in different facets of the work, and who can adapt and improve and strive toward meeting the organizational goals. This makes it very unlikely that you can have some sort of conclusion who is the “best” and who is “on top”, since there is a diversity of skill sets needed to achieve these goals, and they are often shifting.

So instead of “stack ranking” employees, which implies that one employee is inherently better than another (and makes a not-so-subtle argument that it is forever that way), managers need to strategically place employees in roles and projects based on what the managers and employees assess they are good at and their ability to execute. It’s less about who’s the best, and more about what is the best placement to get the work done.

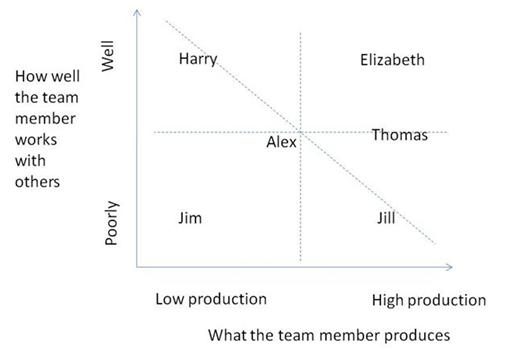

Let’s take a look at the What/How grid to be as a way to be more strategic with a team’s strengths. This grid shows an analysis by a manager of a fictional team, based on “what” the team member produces and “how” they work with others. Other analyses could be performed based on your organizational needs.

In this grid, the manager has assessed that Elizabeth and Thomas as skilled in both productivity and ability to work with others. But the manager also has Harry who seems to get along with lots of people, but doesn’t produce much, and Jill who seems to work really hard but isn’t as focused on relationships. So now the manager, instead of saying, “Elizabeth and Thomas are my top performers”, the manager should say, “What can I do with this group to get the most out of my team?”

I’d put Harry in a role that requires relationships to be forged. I’d make sure I’d give Harry some expectations for what we are looking to get out of those relationships (new leads? sales? higher customer satisfaction? socializing a new program across groups?) and rate him against these expectations. I’d put Jill in a role that is not customer-facing but requires a lot of work output where relationships are less crucial for success, and rate her against what she produces (and diminishing the importance of “how” she produces). Ideally, this most likely feeds to Harry information that makes him better. If I need more customer-facing work and relationship building, I’d put Elizabeth on that, and if I need more work output, I’d put Thomas and Elizabeth at that.

Elizabeth and Thomas are more flexible, which obviously has value, but if the value of customer relationship building is super-important for the team, then perhaps Harry is more valuable than Thomas for now. It isn’t a permanent thing, but a thing that is based on the context of the team’s needs, and not on the context of the employees inherent abilities.

With Alex, I would try to figure out where Alex is most likely to be needed in the near future, and work on giving performance feedback and coaching in the direction where your team is likely to need it. Perhaps Alex can be a back-up to Harry in the follow-up with customers.

With Jim, he rates lowly in two dimensions, which looks like a net-negative to the team, so I would look at the performance management process for him, because it doesn’t look like he’s helping the team at all, and unless he improves (which is entirely possible with the performance management process) there is likely someone else out there who could do his job better.

So instead of saying, “Elizabeth and Thomas” are the most important employees, the manager should first focus on trying to maximize where all employees can most help the team to achieve its goals. This treats all employees as valuable, and is likelier to achieve overall team performance.

This is where the management energy should be spent first and foremost. The shifting dynamics of the team context should be the greater concern, not the ranking of individual employees against one another, since you need the entire team to perform to be successful.

Also note that once placed on this grid, the people are not permanently located there. Any one of them can shift around based on changing circumstances, work stresses and pressures, and individual development.

In this article, I use a very simple “What/How” grid to identify the strengths of the team and to assist with illustrating how a manager can use this simple tool. Another common method is to use the Strength Finder tool from the book Now, Discover Your Strengths, which has many more dimensions and areas of insights and one I would highly recommend any manager do to identify the areas of strengths on the team and then make strategic decisions accordingly.

How much energy does your management team spend in strategically utilizing employee strengths? How does this compare to the amount of time ranking employees?

Related Articles:

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

An obsession with talent could be a sign of a lack of obsession with the system

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

How to use the What-How grid to build team strength, strategy and performance

If you really want to evaluate performance across individuals, here are some things that need to be in place

In my previous article, I discussed how many organizations spend time identifying who the top performers and stack ranking employees, to the detriment of assessing other areas that drive performance. Management teams obsess on determining the best performers are. Once done, this implies you now have what it takes to get ahead in business. It’s an annual rite. Despite this process causing lots of angst, the appearance of accuracy in the face of tertiary impressions, and the general lack of results and perhaps damage it causes, this activity continues to have a high priority for many organizations.

OK, so if you really want to do it – you really want to compare employees — here are some things that have to be in place if you don’t want to cause so much damage and angst in the process:

1. You can compare people only across very similar jobs

Many organizations attempt to compare people across the organization, in kind of similar jobs, and under different managers. Then they try to assess the value of the various outputs of the jobs that had different inputs and outputs. If there were different projects and different pressures, different customers and different challenges, then it will be difficult to say who is the better performer.

Bonus! Three more tips for how manager can improve direct peer feedback

I’ve been writing a lot about peer feedback lately, and here’s why: It can do great things for your team, or it can do bad things for your team. So let’s get it right. Let’s make it a force for good, rather than bad.

In my previous article, I provided three tips for driving the positive outcomes of using peer feedback as a tool for improving your team performance. As a manager, you have to manage how peer feedback is given. If you manage this, your team as a whole will drive for improved performance, not just you.

Let’s continue down that path and explore three more tips for developing a team that uses peer feedback effectively:

4. Phase in giving feedback and who gives feedback

There are lots of situations where you must beware unleashing the feedback-giving ethos:

–A new team member may not be the best person to give feedback. The new team member may not know what the right course of action is. However, that person is also a candidate to receive peer feedback, and hence will begin to experience the culture of giving and receiving peer feedback. But when first starting, perhaps you should not unleash the expectation to give peer feedback right away.

–Similarly, another team member may have trouble using behavior-based language. Don’t encourage this person to give peer feedback.

Tips for how a manager can improve direct peer feedback

Peer feedback can be a tricky thing. When it is given indirectly, such as via 360 feedback surveys, it potentially makes a mess that is hard to clean up. But what about when peer feedback is directly given? There are pros and cons for peer feedback directly given, and perhaps the biggest argument in favor of direct peer feedback is that it multiplies the amount of performance feedback an employee receives.

Use these tips to encourage your team to maximize the pros and minimize the cons:

1. Get the team, in addition to the manager, good at giving feedback

The Manager by Design blog knows how badly given feedback can ruin so many things about the work environment. And there is an epidemic of badly-given feedback out there, and for this reason I have some hesitation to recommend in this post that the lines of feedback be increased, since it could be increased badly given feedback.

However, performance feedback is such an important performance driver that this must be overcome! There are ways to improve how you give feedback and can identify what good feedback looks like. This blog provides a number of tips on how to improve the feedback, from making it specific and immediate to using behavior-based language, to seeking direct observation and feedback opportunities. There are many examples of great training opportunities to learn how to give performance feedback. In the Seattle area, I recommend Responsive Management Systems, which provides services that will improve how you prepare to give feedback and give feedback that gets the results you want. Of particular interest related to this topic is their “Responsive Colleague” program.1

An opportunity to increase the amount of performance feedback on your team

Peer feedback is frequently given via indirect surveys, perhaps as part of a 360-degree feedback program. I would like to argue that this doesn’t really count as peer feedback, since it is time-delayed, indirect, and frequently non-actionable. I’m more in favor of direct peer feedback, since it is specific and immediate, can be focused on improving performance and teamwork. However, there are some reasons to be wary direct peer feedback, as I detail in my previous post.

However, the main reason I’m in favor of direct peer feedback is that it multiplies the amount of performance feedback that team members receive. Let me explain:

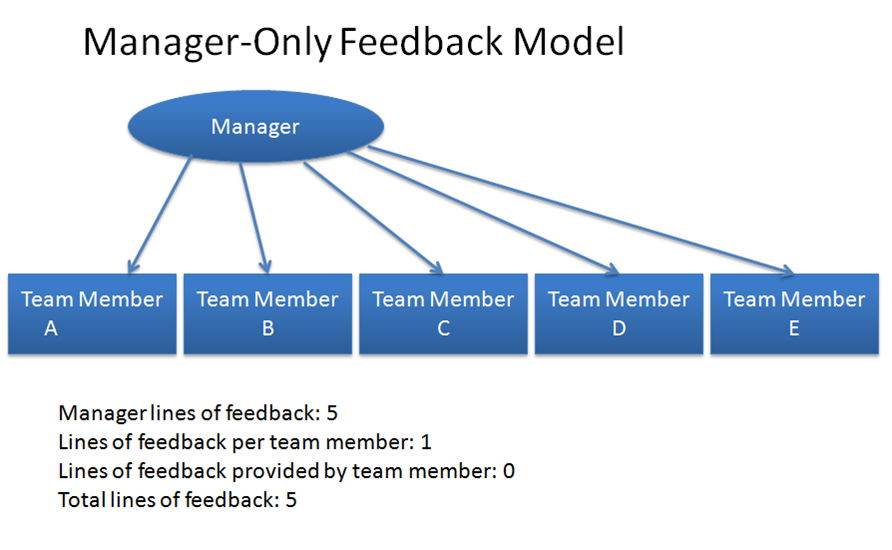

A traditional model for how employees improve their performance is through manager observation, and then the manager provides coaching and corrective feedback. For a team of five people, this is what it looks like:

Look familiar? This is the popular conception for how employees receive feedback on their performance. It is predicated on the belief that the manager has enough expertise in all the areas of the team performance to provide feedback, and the manager actually has the skill to provide feedback, which, alas, is not always the case. When most of us start a job, this is the general mental model that we have. After all, the manager is the one who evaluates our performance, and knows the expectations for performance! Employees expect to receive feedback from the manager on performance.

Examples of how peer feedback from surveys is misused by managers

In my previous post, I describe how peer feedback from 360 degree surveys is not really feedback at all. At best, it can be considered, “general input from peers about an employee.” Alas, it is called peer feedback, and as such, it risks being misused by managers. Let’s talk about these misuses:

As a proxy for direct observations: Peer feedback is so seductive because it sounds like something that can replace what a manager is supposed to be doing as a manager. One job of the manager is to provide feedback on job performance and coach the employee to better performance. However, with peer feedback from surveys, you get this proxy for that job expectation: The peers do it via peer feedback. Even better, it is usually performed by the Human Resources department, which sends out the survey, compiles it, and gives it to the manager. Now all the manager has to do is provide that feedback to the employee. See, the manager has given feedback to the employee on job performance. Done!

Never mind that this feedback doesn’t qualify as performance feedback, may-or-may not be job related, or may-or-may not be accurate.

The incident that sticks and replicates: Let’s say in August an employee, Jacqueline, was out on vacation for three weeks. During that time, a request from the team Admin came out to provide the asset number of the computer, but Jacqueline didn’t reply to this. And worse, Jacqueline didn’t reply to it after returning from vacation, figuring that the admin would have followed up on the gaps that remained on the asset list. Then it comes back a year later on Jacqueline’s peer feedback that the she is unresponsive, difficult to get a hold of and doesn’t follow procedures. This came from the trusted Admin source!

Why peer feedback from surveys doesn’t qualify as feedback

In a previous post, I identified peer feedback from 360 degree surveys as a source of inputs where a manager gets information about an employee’s performance. Peer feedback via 360 degree surveys has become increasingly popular as a way of identifying the better performers from the lesser performers. After all, teams should identify people who get great peer feedback, and do something about the team members who get poor peer feedback. The better the peer feedback, the better the employee, right? Well, maybe. Maybe not. Let’s talk about how peer feedback should be used, and not misused.

OK, peer feedback. As Demetri Martin would say, “This is a very important subject.”

First of all, by definition, peer feedback on surveys is, from the manager’s perspective, indirect reporting of an employee’s performance. The peer gives the feedback via some intermediary source (survey, email request, or, if requested, verbal discussion), and then that information gets interpreted as to what it means by the manager, or perhaps even some third party algorithm.

So it is essentially hearsay. Since it is one degree away from direct observation of performance, peer feedback is inherently more risky to use as a way to provide feedback on an employee’s performance. Here’s why:

The best feedback – or the most artful, as I like to say – has the following qualities, amongst others:

–It is specific

–It is immediate

–It is behavior-based

–It provides an alternative behavior

Let’s see how peer feedback stands up!

Specificity: Peer feedback on surveys comes in the form of a summary of behaviors over an aggregate period of time. Sample peer feedback will say something like, “John is always on top of everything, which I enjoy,” or “John needs to stop checking messages during the team meeting.” Now here’s the rub: This looks like general feedback, but it may be (you don’t know for sure) related to one incident. The “on top of everything” may refer to arranging a co-worker’s birthday party. The “check messages during a meeting” may have happened during the one meeting when his daughter was undergoing surgery. Or it could be something that John always does. You don’t know. It’s general or it’s specific. You don’t know.

Or. . .have you ever seen this kind of peer feedback?

“During the September 18 team meeting, John was checking his messages when he should have been working with the team to brainstorm solutions to resolving the budget shortfall. Then, on the September 25 team meeting, John received two phone calls during the meeting, interrupting the discussion flow about what our strategy for next year should be. Then, on October 2, John. . .”

This kind of peer feedback doesn’t happen on surveys. Instead, you get summaries of behaviors that may be based on a specific incident. . . or not. It may be work-related, or not. You don’t really know.

The Value of Providing Expectations: Positive reinforcement proliferates

In my previous article, I noted how setting team expectations can help a manager identify when and how to provide corrective feedback.

There is another value to providing expectations to your team: It allows you and your team to provide reinforcing feedback, and more of it. Reinforcing feedback, also known as positive feedback, is much easier to give and receive than corrective feedback. The key is to reinforce the right thing!

That’s where the expectation-setting comes in. If the team expectations have been set, then they can be reinforced. On the flip side, if no expectations have been set, then what gets reinforced will be generally random. Some of good behaviors get reinforced, and some of bad behaviors get reinforced.

So if you set team expectations, then you and your team are much more likely to reinforce the desired behaviors. As previously written on this blog, the manager should be spending a good chuck of time reinforcing positive behaviors.

In the example I used in the previous article, was the manager set the following general team expectation:

The team will foster an atmosphere of sharing ideas

In this example, let’s say the team actually conducts a meeting where the various team members support each others’ ideas, and allowed everyone to provide their input. The manager observes this and agrees that this reflects the expectation of “fostering an atmosphere of sharing ideas.”

Now the manager needs to reinforce this! The manager can reinforce this in a few different ways.

1. Feedback to the group at the end of the meeting

At the end of the meeting the manager can say:

“This meeting reflected what we are looking for in fostering an atmosphere of ideas. I saw people on the team asking others for their ideas, and I saw that ideas, once offered, weren’t shot down and instead were praised for being offered. This allowed more ideas to be shared. Thanks for doing this, and I like seeing this.”

The value of providing expectations: Performance feedback proliferates and becomes more artful

I’ve written several articles lately about providing expectations to your team on how to perform. These articles describe how to increase the artfulness of providing expectations or setting expectations for behavior. For example, the expectations should:

— be set earlier rather than later

— include standards of performance where documented

–provided general guardrails of behavior

— should attempt to tie into the larger strategy

I’ve also written articles about how providing performance feedback to your team as a key management skill. Now let’s take a look at an example of how providing expectations can help you in providing performance feedback.

1. Performance feedback you provide happens more naturally, immediately and specifically

If you have provided expectations for how the team works together, and the guardrails of behavior are established in some form, you now have a context and standard of performance to start any performance feedback discussion when you see the need for someone to change what they are doing. Let’s take a look at a performance feedback example: