Annual reviews are awesome artifacts that can be used to improve management skills

The Manager by Designsm blog has documented many issues that annual performance reviews bring to the manager/employee relationship. I’ve written about how they are “toxic”, cause angst, and perpetuate myths both about employee capability and what acceptable management practices are.

But I’m not totally against annual performance reviews. Sure, I don’t think that they are effective at actually evaluating performance of the people they are evaluating, but I do think that they are extremely effective at revealing the practices of the managers conducting the reviews. They are a treasure of information that provides a window into how the manager relates to her employees, how she assesses performance, and the degree of effort taken to help the employees improve.

So I say keep the performance reviews, because this is the only infrastructure – however flimsy (I can’t elevate it to the level of “design”) — that many organizations have that actually require managers to perform management-related tasks, such as setting expectations and goals, assessing and discussing performance of the employees, and actually committing this to a document that demonstrates that this task has been performed.

Five more markers and examples of what a good annual review looks like

In my previous article, I provided five markers of what a well-conducted annual review looks like. Let’s look at some more. It is possible to actually conduct an annual review well, but this is no guarantee. So let’s keep looking for those precious markers of a manager who knows how to use the annual review for good, rather than perpetuate it as a tool for suffering.

Marker #6: Improvement is germane to the discussion

If the annual review has any discussion about where the employee’s skills and performance was at the beginning of the year, and a comparative analysis at the end of the year – in those same skills – then this means that the manager is actually concerned with increasing the capability of the organization. I would consider this generally a good thing. For example:

“At the beginning of the year, we discussed how we can improve Alex’s presentation skills, as she frequently presents business partners. During the year Alex sought mentoring and feedback in this area, and the results show that this effort has paid off. Our partners have reported that they find her speaking style inviting and informative, and Alex has consistently been able to meet the objectives of the presentations.”

Marker #7: References to the goals

First, a marker would be that the employee and the team actually have some sort of goals. That would be the first marker of a good performance evaluation, as it provides something against which the manager evaluates the employee. Now, the second part of this is if the manager actually references the goals in making the evaluation.

“We had the ambitious goal at the beginning of the year to implement a new payroll system to further streamline what was before a highly labor-intensive project. Jeanine was a key part of the team that scoped the project, identified the goals of what success of the project was. Jeanine managed the vendor selection process, kept the team focused on the desired outcomes, and ensured that the team understood what was in scope and out of scope via her weekly communications. This was a key factor in assuring that the project stayed on track, which it did. The new payroll system was launched on time earlier this year, and has significantly reduced the processing time.”

Marker #8: Teamwork is referenced by both the employee and the manager

The individual performance review necessarily focuses on the individual. I consider this bad management design, as individual work is good, but teamwork can create greater outcomes. Almost all workgroups rely on teamwork. Managers and employees can transcend the design by invoking what teamwork happened during the review period. Let’s say that the manager talks about the great teamwork that the employee engaged in. Let’s say that the employee mentions how she contributed to building the team, and how she made an effort to improve the capability of the team, or looked out for the interest in the team. This would reflect that the manager and team are actually concerned with the power of teamwork over the expectation for an individual to perform independently of teamwork. Here’s an example:

“Jonathan demonstrated that he is an excellent team player by creating a process document that showed how to complete a task that many team members performed irregularly. This helped the team gain some efficiencies, and inspired other team members to make similar efforts. The team is healthier as a result of Jonathan’s efforts.”

Marker #9: Goals seem to have a similar voice and scope across team members

Many annual reviews have a section where the employee’s goals are documented. One could look at the goals of all the team members across a managers’ team. Imagine, if you will, goals that seem to have a similar tone, similar metrics, and similar scope across team members. They don’t have to be exactly the same, because not all roles are the same, but if the goals are all striving toward a similar metric or output, this demonstrates that the manager knows what the team is striving to do, and has actually infused it in the goals. When the goals seem to be similarly written, we also know that the manager has provided input and perhaps even co-authored the goals – or this is sometimes tough to imaging – this was done as a group. Too many times we see managers push down the goal writing process to the individual employees, which results in, by definition, different looking goals. Let’s celebrate those times when we see goals across the team show some kind of consistency across the team.

Marker #10: There is agreement between the employee and the manager

If a manager and employee seem to say that they agree about things on the performance review, this reveals that the employee and the manager actually talked about these things prior to the annual review. Differences in what the results were, what the impact of the employee’s actions and whether or not the employee performed at a high level – well these were resolved external to the review, as should be the case. Many managers wait until the review to resolve lingering disagreements, sometimes even using the review to create new ones, but those managers who seek alignment and understanding with their employees throughout the year, and don’t wait until the end of the year should be recognized as superior managers. Here’s what alignment looks like:

Employee: “I increased sales by 15% through my efforts to reach out to a new customer base.”

Manager: “I agree with the employee. He was effective at identifying a new target market, and then executing the strategy of accessing the market.”

See? no debate! Do you think that a debate might have happened during the year to get to this agreement of what the employee’s efforts were and what were the estimated results? Yes. Does it appear on the annual review? No, but the agreement of the results of the discussions do appear.

We should celebrate when managers do a great job on the perilous annual performance review, and do whatever we can to increase the chances of a well-conducted review.

Have you seen these markers of success on a review? Let’s hear your stories!

Related Articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

How to neutralize in advance the annual toxic performance review

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

I’ve recently published a series of articles that describe how annual reviews reveal more about the manager than the employee. The examples I’ve provided focus on examples of bad management practices that could cause damage and general resentment in the manager/employee relationship. But of course not all annual reviews are conducted poorly.

I know that for some of you out there this might be hard to believe. Just as it is easy to recognize poor management practices in action on an annual review, there’s the ability to identify when a review is done well. Here are some examples of markers of a well-conducted employee performance review:

Marker #1: Level of detail

A well-conducted annual review will show that both the manager and the employee have a mastery of the details of the role being reviewed. The details should include specific actions that the employee performed. The manager can demonstrate involvement in the actual work by discussing how she actually reviewed the work and found it at the desired performance level and what the impact of the work is, or is anticipated to be.

Marker #2: Agreement of metrics

First, let’s assume that there are success metrics (yes, numbers) that are documented somewhere on the review. That is a good sign. Second, let’s say that the manager and the employee BOTH refer to the same numbers on the review. That’s another good sign. So then we know that both the manager and the employee seem to be striving for the same numbers. That’s a third good sign. (We’re taking baby steps here. I would also be great if the metrics were tied to drivers of business/organization success – but let’s start really basic and have the employee and manager agree on a few metrics first.)

Marker #3: Referencing performance feedback/strategy sessions

When either the manager or the employee reference in the review actual feedback conversations (or what I also refer to as “employee strategy sessions”) that happened external to the review context, this is a good sign. That means that the manager has taken an active interest in the employee’s ability to perform the job well, and has taken the time to coach the employee. Also imagine the employee referencing in the review having been coached, taking the feedback and applying it, and then getting better results. That would be even a better sign.

Marker #4: The performance feedback/strategy sessions are related to the job functions and results

It’s one thing to have feedback discussions throughout the year, but it’s another to have feedback discussions that actually revolve around performing the job better. Many times managers stick to things that are closest to the manager, but are at best indirectly associated with doing the job:

“Jeff is late for our team meetings”

“Anne didn’t attend the all-team meeting”

“Isabelle needs to speak up during the team meetings”

“Mark brings up problems during 1:1 meetings”

OK, so those seem to be things revealing a lot about the employee/manager logistics, but nothing about the job. How about instead:

“Jeff created a strategic business plan that researched the competitive landscape. We identified some new tools he can use to create deeper understanding of our competitors, and he introduced to them to the organization.”

“When we found errors coming from our vendor, Anne identified the top issues and worked with the vendor to reduce errors and costs.”

“In looking at the contracts Isabelle writes, they are consistent, keep the company’s interests at the forefront, and delivered on time.”

“Mark is skilled at finding issues in the organization, and raising them such that they help the team run. One example is our outreach efforts to our partner teams. He identified that this was an issue, and he proposed that he and I meet with them to better understand how we work together. The result was that the partner teams have included us in key decisions that we wouldn’t have been involved with otherwise.”

Marker #5: An outside party can actually identify what the job is by reading the review

If you look at the above examples, you can actually start to guess what the employee actually does. This should be the focus of a review – most of the commentary should be on what the employee did, and how well, and whether they met the goals or improved things.

These are some (not all) of the markers of a well-conducted annual review. If you have managers that display these markers, perhaps you should praise them for doing this well?

Have you seen these markers on an annual review? Or is it more common to see the markers of poorly conducted reviews?

Related Articles:

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

How to neutralize in advance the annual toxic performance review

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

The annual review reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance (part 4)

In my previous articles (here, here and here), I discuss how the annual review process reveals more about the manager than the employee. The annual review’s text may be about the employee’s performance, but what really is powerful about the performance review is the subtext – what the review reveals about the manager’s practices as a manager.

Here are some more examples of what you can see in a performance review and what it says about the manager:

1. The incident that defines the whole year

Annual reviews were developed to review the whole year. Yet many reviews boil down to a particular incident during the course of the year. Both the manager and the employee may recount the incident, and use this as the basis for the employee’s performance. It might be interesting to see what the incident is. Did the employee disagree with the manager? Was the employee supported by the manager through the incident, or left hung out to dry? When this is observed, know that employees will work extra hard to avoid “the incident”, or work hard to re-define “the incident.” In any case, it should be rare, not common, that a single event could define someone’s work, and if that’s the case, it should be reflected in their goals.

2. Bias

Many employees fear that their manager has a bias toward or against various members of the team. The annual review is a great place to test this thesis. Does the manager reveal in the comments a preference to one employee over another? Is one employee looking for attention and another basking in it? One can read for tone as well as content to reveal the answer to these questions.

3. The lack of performance-based language

The Manager by Designsm blog writes frequently about using behavior-based language, also known as performance-based language (read here for a primer on how to tell if you are using performance-based/behavior-based language). The annual review should be a bastion of performance-based language, yet it is often the opposite. “Michael is the best!” “Andrea is a real go-getter!” “Pete doesn’t have what it takes,” “Aaron needs a better attitude.” These are generalizations and value judgments that reveal that the manager does not think in behavior-based terms, which indicates that the employee is probably being evaluated on impressions rather than performance.

4. The difficult review discussion

External to the actual form, do you have managers who dread the review period, talk about “difficult” reviews, and otherwise find the process difficult and cumbersome? This teaches you that the manager could be letting the management tasks slide until the review period comes along. There will be a lot of pent-up angst when this happens, and the review discussions will be necessarily difficult if you are trying to resolve a year’s worth of issues in one discussion. Remember, it is supposed to be a re-view, not a view into the employee’s performance.

5. The wildly variant employee ability across time

In this situation, the employee is a “star performer” one year, and a “weak performer” another year. What changed? It could be the employee, but if you assume that, you’re going to be right only some of the time. Other things probably have changed – the manager and/or the work challenge. If an employee was great on one team and terrible on another team, is it really the employee? If the employee was supported, had good processes and reasonable expectations, and they did well, that’s great. If the same employee joins a team with no processes, unreasonable work expectations, and a difficult political environment, we have just learned the difference of the managers (and the manager of managers), not the employee.

6. Only things the manager observes

A manager often comments on the review the things about the employee they have directly observed. This is generally a good idea, because the rest is hearsay. But what if we learn through the comments what it is that the manager has directly observed? If the manager only comments about the behavior of the employee during 1:1 discussions, team meetings, and emails/status reports to the manager, then we know that the manager is evaluating only employee behaviors in the context of interacting with the manager. You can forget about the work output, how the employee interacts with colleagues and customers, and other areas of performance. But if that employee is quiet during the team meeting, then it will appear on the review.

7. Relying on what “others” say

Similarly, a manager may focus on what others say to rate the employee. This could come from the boss’s boss, other team members, or the prior manager. If there is a dearth of other areas that are examined about the employee’s work output and ability to produce results, then this should be a cause of concern that the manager is more focused on political aspects of the work environment (“what are others saying”) and less on the work output and ongoing behaviors (“what did the employee do.”)

So for the budding Management Designers out there, how do you use the Annual Review to understand the management behaviors? Or are you leaving this rich artifact on the table and relying on other channels to learn about your managers?

Let me know your stories of how managers reveal their management practices on performance reviews.

Related Articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

Behavior-based language primer for managers: How to tell if you are using behavior-based language

Behavior-based language primer for managers: Avoid using value judgments

The annual review reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance (part 3)

In my previous articles here and here, I discussed how the annual review process reveals more about the manager than the employee. The annual review’s text may be about the employee’s performance, but what really is powerful is the subtext – the manager’s practices as a manager.

Here are even more examples of what kinds of things are revealed about a manager in an employee performance review:

1. The Fight

Two articles ago, I cited “the debate”, which I characterized as a disagreement on the review over what happened over the course of the year. But sometimes you’ll see actual arguments spill over onto the review. The argument may be over points of fact, or points of interpretation, but if the two parties are extending their argument into written form when the annual review is written, then you know, at the minimum, that the manager is comfortable not resolving disputes, and letting them extend into a variety of forums and formats, and it probably doesn’t stop at the review.

2. Egocentrism

Many managers will talk about their own actions and contributions on an employee’s review. It’s one thing to talk about the team accomplishments, but when you see a manager say, “I was able to help Jim achieve an increase in sales,” or “I made a great hire in Tammy,” you can infer that the manager has more focus on him or himself than the team. Just count the number of “I’s” in the manager comments and you can get a feel for this.

3. The one good thing one bad thing

I have commented on this in a prior article – but this is a good time to revisit it. Many managers believe that they need to be “fair” in providing one good piece of feedback and one bad piece of feedback on an employee. “Jim was able to deliver a high volume of work, but sometimes his emails can be too long.” Doing this makes little sense, because typically employees do go to work and then do one thing good and one thing bad. If there is something that the employee needs to get better at to do her job, then this needs to be articulated as something the manager and the employee are already working on. It reveals a lot about a manager who waits until the review to articulate the wrong things the employee does without having any reference to an effort to improve the employee in that area. Perhaps this frequently happens because the “bad thing” that is cited is often irrelevant to the employee’s performance, “Max didn’t go to the team event.”

4. Areas irrelevant to the performance

The annual performance review is often a treasure trove of irrelevant feedback. Many managers will cite events that are not relevant to meeting goals (what time the person comes in every morning, the length of emails, for example). Look closely at what the manager critiques and praises. Is there a connection to the team achieving the metrics, or is simply something that is generally considered bad (being late on occasion, being slow to respond on email) or good (setting up a weekly happy hour), but not necessarily directly connected to work output.

5. The blank career development area

There are lots of places on the form to fill out. Sometimes managers do not fill in certain areas. A common area that often goes untouched is the career development plan. Many review forms have a “looking forward” section that discusses what the employee plans to do to develop his or her career. If this section is blank – and it often is – then you know for sure that the manager isn’t engaging in this discussion with the employee. If the manager does have it filled in, and it looks robust and connected to the employee, then you know that this is something the manager is good at.

But wait, there’s more! Tune in next week for more ways the review reveals more about the manager than the employee. What stories do you have?

Related articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

The Cost of Low Quality Management

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

Tenets of Management Design: Managing is a functional skill

The annual review reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance (part 2)

In my previous article, I discussed how the annual review process reveals more about the manager than the employee. The annual review’s text may be about the employee’s performance, but what really is powerful is the subtext – the manager’s practices as a manager.

Here are some more examples of what kinds of things are revealed about a manager in an employee performance review:

1. The lack of detail

The manager usually has a comment box in an employee review form. If the manager does not write much in it, what does that tell you? Probably that the manager has no idea what the employee did over the course of the year. Compare the following:

“Joe had a great year. He met all of this goals and is well-liked on the team.”

“Tiffany created a new system that was implemented across the team to improve communication, streamline processes, and create more accountability. She identified the largest issues facing quality teamwork, and her efforts in this area contributed to a better team understanding of the deliverables and timelines.”

In the second example, the manager appears to know what Tiffany did. In the first example, it is not clear whether the manager even knows who Joe is, and what he does.

2. The lack of discussion of improvement

One of the tasks of a manager is to facilitate an ever improving team atmosphere and capability. Or, at the minimum, get it to an acceptable level and keep it there. But what if you never see any language that expresses any effort to improve the team or its members?

Something like, “At the beginning of the year, Andy and I discussed improving his follow-through on resolving quality issues in his work. We worked together to identify how we can improve in this area, and during the year, Andy had many fewer issues in this area. In fact, Andy is now a team champion on how to assure our team’s work output is both timely and with quality.” This indicates a drive for improvement.

Instead we often see the flat, “Andy has quality issues.” In this case, we quickly learn that the manager sees no responsibility in improving Andy’s quality issues. This indicates a quality issue of the manager.

3. The disconnect from goals

Many performance reviews have a section that require employees and managers to compare the actual results of the work with the goals established at the beginning of the review period. It is often observed that managers will not comment on these goals and whether or not they were met by the employee, and instead focus on personality elements. Perhaps you’ve seen something like: “Joan brings a lot of fun to the team!” “We love Harry’s sense of humor and positive attitude.” That’s on the positive side. On the negative side, it might be, “Marty is always late for meetings” or “Patrick could improve his attitude” or “Maurice could be more helpful with other team members.”

If the manager writes something that is not connected to the goals and does not reveal her opinion as to whether or not the employee met the goals, we learn that the manager didn’t take the goals seriously in the first place, or doesn’t know whether they were met.

4. Comparison of goals across team members

Sticking to the topic of goals, one exercise is to compare the goals across the manager’s team members, which are usually documented on the annual review. Are they the same? Do they appear to lead to a team strategy? Or do they appear written independently by the individual members of the team? One team member may have tons of goals, and another may have hardly any. Are one set of goals very crisp and another set of goals unformed and vague? That can happen if the manager is not taking the goal-writing process seriously, and has not provided input.

5. Expectation of teamwork

The manager is ostensibly a leader of a team, not a series of individuals. However, the annual review typically has very little commentary about how team members helped one another. If the manager does not have discussions somewhere in the review (goals, what the team achieved vs. what the individual achieved) that identify the quality of teamwork, then we know that this is not a priority of the manager. Is this the kind of management practices we are looking for?

My next article will discuss even more examples of when a manager reveals more about herself on the employee’s performance review.

Do you have examples of when the review says more about the manager than the employee? Send them my way!

Related Articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

The Cost of Low Quality Management

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

The annual review reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance (part 1)

I have written in the past about “the annual toxic performance review.” The basic point is that this is the only time many managers provide insights – the view – on how the employee is performing, is during the re-view. The view in to the employee’s performance is often during the re-view. Kind of ironic.

Another ironic situation is that the employee’s annual review usually reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance. Yes, the review covers all sorts of aspects of the employee’s performance, usually both from the employee’s perspective and the manager’s perspective. That’s the text.

But the subtext of any employee performance review is how well that manager managed the employee during the review period. And looking at a manager’s reviews from this perspective will quickly reveal lots about how that manager manages.

Let’s take a look at some examples of how the review reveals information about the manager:

1. The debate

Many times you will see a debate emerge about the employee’s performance via the employee’s self evaluation and the manager’s comments. If there is disagreement, this reveals that the manager has not discussed the employee’s performance openly with the employee during the year, and has instead waited until the performance review to share his thoughts. The employee, perhaps anticipating this debate, will submit multiple pieces of evidence (metrics, stories, customer quotes) to pre-empt the anticipated contrarian position of the manager. It’s interesting to see if the manager’s comments actually address these pieces of evidence, or ignore them and make generalizations about the employee’s performance.

2. Performance Feedback on the review

Many times you will see a manager finally take that step and provide feedback to an employee via the review. “Jim needs to be more accountable.” “Alex needs to manage meetings better.” “Alyssa has quality issues that have hurt the team.” “Patrick needs to connect with his peers more.” (Note: As these are generalizations, they are poor examples of performance feedback, but nonetheless examples of performance feedback likely to be found on the review.) If the manager gives this feedback and does not reference a conversation to this effect in the review (i.e., “We discussed how Patrick can engage with his peers”), then the manager has simply waited until after the review period to give performance feedback. As discussed many times in this blog, this is the most un-artful way to manage and to provide performance feedback, as it is neither specific nor immediate.

Yet so many managers do it today, it has become almost a norm. Should you see this on your organizations’ annual performance reviews, expect there to be contempt for the managers in your org.

3.The “keep it short” instruction and subsequent debate

Many annual review forms have an employee self-evaluation section, and then a manager comment section. Managers often give instructions to their employees to “keep it short.” That is – don’t write much about your performance. This reveals much about the manager – a) The manager does not want to hear about good work being done by the employee, and wants to deny that opportunity of expression b) The manager is trying to limit discussion of and knowledge of what the employee accomplished c) Apparently doesn’t want to read more than a page of text and; d) Wants to give negative feedback during the review (see point 2 above), but fears that the employee may submit evidence that this negative feedback is incorrect, so the best mitigation strategy by the manager is to cut off discussion. Often there will be more debate – in the review form itself, prior to the discussion, and during the discussion – about the amount of text an employee can enter in the review form than there is a discussion about the employees performance. Crazy.

What are examples you have of managers revealing more about their performance on the annual review? Send them to me!

In my next article, I’ll provide more examples of how the annual review reveals more about the manager than the employee.

Related articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

An example of giving specific and immediate feedback and a frightening look into the alternatives

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

If you really want to evaluate performance across individuals, here are some things that need to be in place

In my previous article, I discussed how many organizations spend time identifying who the top performers and stack ranking employees, to the detriment of assessing other areas that drive performance. Management teams obsess on determining the best performers are. Once done, this implies you now have what it takes to get ahead in business. It’s an annual rite. Despite this process causing lots of angst, the appearance of accuracy in the face of tertiary impressions, and the general lack of results and perhaps damage it causes, this activity continues to have a high priority for many organizations.

OK, so if you really want to do it – you really want to compare employees — here are some things that have to be in place if you don’t want to cause so much damage and angst in the process:

1. You can compare people only across very similar jobs

Many organizations attempt to compare people across the organization, in kind of similar jobs, and under different managers. Then they try to assess the value of the various outputs of the jobs that had different inputs and outputs. If there were different projects and different pressures, different customers and different challenges, then it will be difficult to say who is the better performer.

How to be collaborative rather than combative with your employees – and make annual reviews go SOOO much better

Many managers botch the annual review process. There’s this persistent idea out there that the manager needs to provide “one good thing, one bad thing” on an annual performance review. However unlikely it is that the employee does an equal amount of damage as good over the course of the year, this model seems to persist. Many times, managers will actually go fishing for incidents that are bad. They’ll try to find those moments where the employee said something wrong, missed a step, or caused friction on the team. The manager will fastidiously wait for the annual review and then spring it upon the employee – Aha! You did this bad thing during the year! And I get to cite it on the review.

Well no more of that!

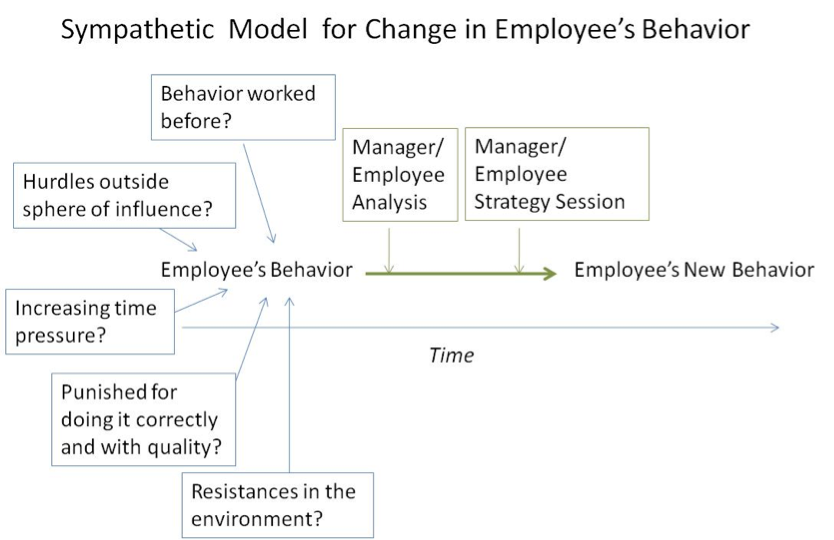

I propose the sympathetic model of performance feedback. In the sympathetic model, the manager looks at both the individual and the system in determining what the employee ought to have done differently (if anything) and what ought to be done differently in the future.

Here is the sympathetic model: (Click for larger image)

When you look at an employee’s actions this way, you can see that there may be some greater forces that went into the employee’s behavior. So instead of using a bad incident to cite what is wrong with the employee, the sympathetic model asks that managers engage in analysis and discussion with the employee to figure out what drove the behavior. Then the manager and the employee strategize on what to do next, and what should be done in the future.

Tenets of Management Design: Identify and reward employees who do good work

In this post, I continue to explore the tenets of the new field this blog pioneers, “Management Design.” Management Design is a response to the poorly performing existing designs that are currently used in creating managers. These current designs describe how managers tend to be created by accident, rather than by design, or that efforts to develop quality and effective managers fall short.

So today’s tenet of Management Design: Design ways that managers consistently identify and reward employees who do good work

This seems like a somewhat obvious tenet that should occur naturally in any organization. The employees who do good work should be identified and rewarded. However, it doesn’t seem to work out that way enough. How many times have we seen it that underperforming employees jockey for visibility and accolades, while the high performing employees feel like they are being ignored or taken for granted? How many times have we seen managers not give thanks or offer praise when it is well earned?