A second phantom job many employees have: Managing perceptions of others

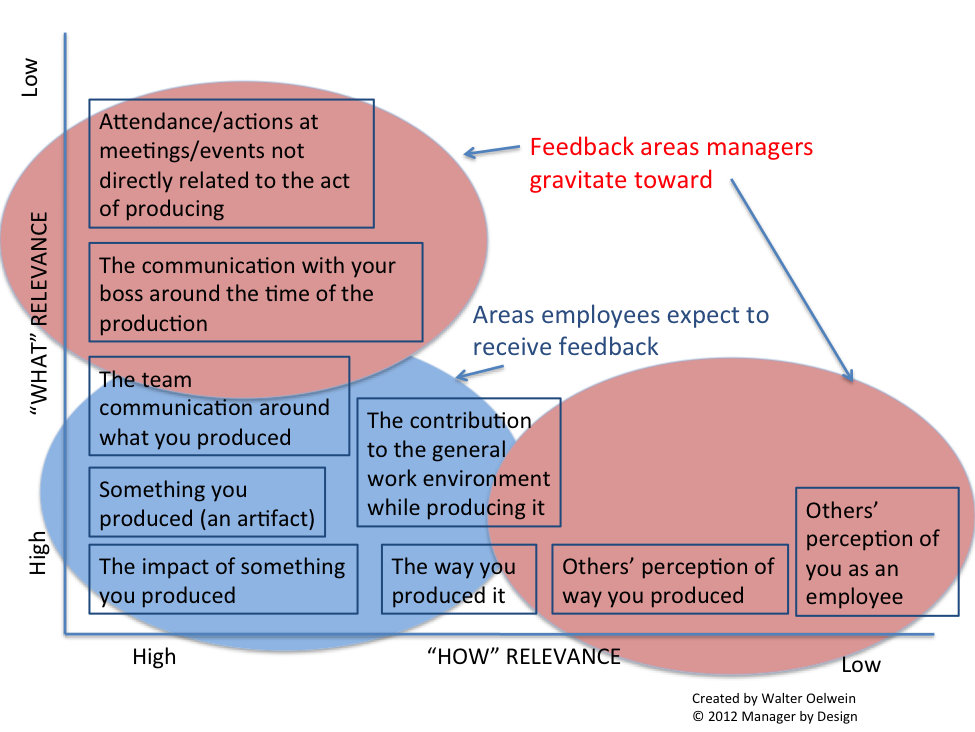

In my previous article, I shared a model to determine the relevance of the performance aspect of performance feedback that many managers give to employees. Here’s the model:

In looking at the upper left corner of this model, many managers create, via the act of giving performance feedback, a second job for the employee: How the employee performs in front of the boss.

So now the employee has two jobs: 1. The job and 2. The job of performing in front of your boss.

The model reveals also in the lower left corner that when a manager gives performance feedback, a third job is often created:

3. The job of managing the perception of others in how you perform your job. Read more

How to use peer feedback from surveys for good (it’s not easy) – Part 2

This article is the second in a series on how managers can better use peer “feedback” from surveys. In general, a manager should be dubious about the quality of feedback that information provided on peer feedback surveys, since they are non-specific and time delayed. At best, this information provides clues and subtext for what is actually happening, and don’t reach the bar of performance feedback, but instead is general info. In the previous article, I discussed how managers should

- Treat the info as clues

- Stick to directly observed behaviors

- Ask for specific and immediate feedback from peers (instead of waiting for the survey to come around)

Today, I’d like to focus on using this information that the survey provides to understand the greater system that is driving the performance of your employees.

4. Use peer feedback as a basis for a strategy session with your employee

I’ve written before about how when giving performance feedback, isn’t always about the individual performance of an employee. Many times, peer feedback can reveal these systemic challenges with the job.

How to use peer feedback from surveys for good (it’s not easy) – Part 1

I’ve been writing a lot about peer feedback lately. What’s interesting is that peer feedback is often about the subtext of what happened between the peer and the employee. The manager looks deeply into the peer feedback to identify the hidden meaning of what the peer was getting at. But what about the thing above the subtext, the thing right there on the surface? What’s that called?

The text.

(Thanks to Whit Stillman’s Barcelona for help writing the opening of this article)

In this case, the text is the actual employee behavior, and this provides a clue for how managers should use peer feedback.

1. Treat peer feedback as clues, hidden meanings and shadowy innuendo

If you get a peer feedback report (often the result of some sort of “360 degree survey” conducted by the HR department), understand that this is a series of random snapshots into an employee’s behavior. Treat it as such. When the peer feedback says, “Jeremy is the greatest!” that means something good, but we’re not really sure. When the peer feedback says, “Jenny does so much to make this a strong team.” There’s something there about teamwork. It’s interesting, but we don’t really know what that means. When the peer feedback says, “Anthony never does any work.” This means that someone somewhere objects to Anthony’s performance. We’re not sure to what exactly this is referring, but there is something there, we think.

In other words, it is all unverified information, but it might give you some clues to something, or maybe not.

Examples of how peer feedback from surveys is misused by managers

In my previous post, I describe how peer feedback from 360 degree surveys is not really feedback at all. At best, it can be considered, “general input from peers about an employee.” Alas, it is called peer feedback, and as such, it risks being misused by managers. Let’s talk about these misuses:

As a proxy for direct observations: Peer feedback is so seductive because it sounds like something that can replace what a manager is supposed to be doing as a manager. One job of the manager is to provide feedback on job performance and coach the employee to better performance. However, with peer feedback from surveys, you get this proxy for that job expectation: The peers do it via peer feedback. Even better, it is usually performed by the Human Resources department, which sends out the survey, compiles it, and gives it to the manager. Now all the manager has to do is provide that feedback to the employee. See, the manager has given feedback to the employee on job performance. Done!

Never mind that this feedback doesn’t qualify as performance feedback, may-or-may not be job related, or may-or-may not be accurate.

The incident that sticks and replicates: Let’s say in August an employee, Jacqueline, was out on vacation for three weeks. During that time, a request from the team Admin came out to provide the asset number of the computer, but Jacqueline didn’t reply to this. And worse, Jacqueline didn’t reply to it after returning from vacation, figuring that the admin would have followed up on the gaps that remained on the asset list. Then it comes back a year later on Jacqueline’s peer feedback that the she is unresponsive, difficult to get a hold of and doesn’t follow procedures. This came from the trusted Admin source!

Why peer feedback from surveys doesn’t qualify as feedback

In a previous post, I identified peer feedback from 360 degree surveys as a source of inputs where a manager gets information about an employee’s performance. Peer feedback via 360 degree surveys has become increasingly popular as a way of identifying the better performers from the lesser performers. After all, teams should identify people who get great peer feedback, and do something about the team members who get poor peer feedback. The better the peer feedback, the better the employee, right? Well, maybe. Maybe not. Let’s talk about how peer feedback should be used, and not misused.

OK, peer feedback. As Demetri Martin would say, “This is a very important subject.”

First of all, by definition, peer feedback on surveys is, from the manager’s perspective, indirect reporting of an employee’s performance. The peer gives the feedback via some intermediary source (survey, email request, or, if requested, verbal discussion), and then that information gets interpreted as to what it means by the manager, or perhaps even some third party algorithm.

So it is essentially hearsay. Since it is one degree away from direct observation of performance, peer feedback is inherently more risky to use as a way to provide feedback on an employee’s performance. Here’s why:

The best feedback – or the most artful, as I like to say – has the following qualities, amongst others:

–It is specific

–It is immediate

–It is behavior-based

–It provides an alternative behavior

Let’s see how peer feedback stands up!

Specificity: Peer feedback on surveys comes in the form of a summary of behaviors over an aggregate period of time. Sample peer feedback will say something like, “John is always on top of everything, which I enjoy,” or “John needs to stop checking messages during the team meeting.” Now here’s the rub: This looks like general feedback, but it may be (you don’t know for sure) related to one incident. The “on top of everything” may refer to arranging a co-worker’s birthday party. The “check messages during a meeting” may have happened during the one meeting when his daughter was undergoing surgery. Or it could be something that John always does. You don’t know. It’s general or it’s specific. You don’t know.

Or. . .have you ever seen this kind of peer feedback?

“During the September 18 team meeting, John was checking his messages when he should have been working with the team to brainstorm solutions to resolving the budget shortfall. Then, on the September 25 team meeting, John received two phone calls during the meeting, interrupting the discussion flow about what our strategy for next year should be. Then, on October 2, John. . .”

This kind of peer feedback doesn’t happen on surveys. Instead, you get summaries of behaviors that may be based on a specific incident. . . or not. It may be work-related, or not. You don’t really know.

More reasons the big boss’s feedback on an employee is useless

Perhaps I’m obsessing about this scenario too much, but I just can’t get out of my head the damage that managers of managers cause when they start assessing employees not directly reporting to them. I call this “tagging” an employee.

In a previous post, I describe the moment where a “big boss” (the employee’s manager’s manager) meets with an employee (or even just hears something about an employee or sees a snapshot of the employee’s work) and provides an assessment of the employee. “That employee really knows what she’s doing!” “That employee doesn’t seem to have his head in it.”

The problem? There are many:

–It rates the employee on behaviors not directly related to doing the job, but it’s based on an abstracted conversation about the work or a limited impression of the employee.

–It puts the manager in the middle in a situation where it would seem appropriate to correct the employee, even when it is inappropriate.

I describe what the manager ought to do about this here. But I’m still obsessed with the peculiar angst that this kind of indirect feedback will create in the employee – even when the “feedback” is good. So before I dive into my obsession, my advice to the managers of managers out there: Don’t provide assessments on an employee. Keep it to yourself. If you are really into assessing an employee’s value, you have to do the work of direct observation of work performance.

Now, let’s look at this “feedback” from the employee’s perspective and the damage it causes in an organization:

When a big boss starts trying to identify the top performers and the bottom performers based on their limited interactions, here is a survey of the damage it causes:

Makes employees one-dimensional: The employee immediately transforms from a multi-talented, hard-working, problem-solving contributor to whatever the “tag” is. This is bad even if the tag is good! If the tag is “hard working”, it diminishes the problem-solving, multi-talented part. It also creates a cloud around what the employee does the whole time at work, and instead puts a simplistic view of the employee’s value.

Assumes that the employee is like that all the time: Similarly, if the employee does a particular thing that gets the big boss’s notice, then that is the thing that the employee has to live up to or live down. For example, if the employee does a great presentation, that is what the employee is seen as being good at – the presentation, and the employee is expected to be presenting all the time to have value. There’s no visibility into the teamwork, project management, collaboration, technical insights, or creativity that went into the presentation. Just the presentation. Then if the person is not presenting all the time, then perhaps they are slacking off? That’s what the big boss might think!

What a manager can do if the big boss puts a tag on an employee

In my previous post, I described a common scenario and the mess it makes:

An employee meets with the big boss (the manager’s manager) in what is often called a “skip level” one-on-one. Or the big boss sees – or hears about — some output of an employee, representing a small fraction of the employee’s output. The big boss then makes a judgment on the employee – what I call a “tag” on the employee. That tag now sticks on the employee. It creates a big mess that puts the manager in a bind – how do you address this employee’s tag?

Here are tips for what the manager caught in the middle can do to handle the tag – whether good or bad.

1. Keep the tag in mind and wait for observed behaviors that are consistent with “the tag”

Ok, if the manager’s manager (“big boss”) is so keen at identifying employee’s essence and value, then surely there will be plenty of opportunities to observe directly the performance of the employee that has earned that tag. Whether the tag is “negative attitude” or “rock star”, the manager needs to wait for opportunities to see behaviors that fit with this tag, and correct those behaviors.

If the manager is keeping a performance log on the employee, these trends should manifest if they are correct, and fail to appear should they be incorrect.

2. Ignore what your manager says and do your job of managing

Almost the same as the point above, but subtly different. It doesn’t matter what the boss’s boss says. If you are managing your employee, work with your employee to make sure he meets performance expectations, provide feedback that drives to the desired behaviors, then, if the employee is performing the job duties according to expectations, then it kind of doesn’t matter what the boss’s boss says. Your assessment is based on better data and you can justify it.

How to use strategy sessions as a way to manage indirect sources of info about your employees (part 3)

This is the third part of a three part series in which I describe how managers should use strategy sessions to address indirect sources of information. Many managers react to indirect sources of information and pass it along as feedback, when instead they should focus on direct sources of information for providing performance feedback. When dealing with indirect sources of info, I advocate for “strategy sessions.”

In the example I’m using in this series, you’re receiving information from your employee’s peers and partners that the employee is being “difficult” in meetings. In my previous articles (part 1 here, and part 2 here), I describe the first six steps for managers to take:

1) Make sure it’s important and worth strategizing about

2) Introduce the conversation as a strategy session

3) Introduce the issue that needs to be strategized share the information that is driving the need for discussion

4) Ask for the employee’s perspective on what the issue is

5) Find points of agreement on what the issue is

6) Strategize on how to resolve the problem

In today’s article, I wrap up the steps for conducting a strategy session with your employee:

7. Agree on what both of you plan to do differently

Since you never directly observed the original behavior, you can’t give quality feedback on the behavior. You can, however, agree on what should be done moving forward. This is a form of providing expectations of behavior. As a result of the strategy session, you and your employee may agree to the following:

How to use strategy sessions as a way to manage indirect sources of info about your employees (part 2)

This is the second of a three part series in which I describe how managers should use strategy sessions to address indirect sources of information about their employees. Many managers react to indirect sources of information and pass it along as feedback, when instead they should focus on direct sources of information for providing performance feedback. When dealing with indirect sources of info, I advocate for “employee strategy sessions.”

In the example I’m using in this series, you’re receiving information from your employee’s peers and partners that the employee is being “difficult” in meetings. In my previous article, I describe the first three steps for managers to take:

1) Make sure it’s important and worth strategizing about

2) Introduce the conversation as a strategy session

3) Introduce the issue that needs to be strategized share the information that is driving the need for discussion

In today’s article, we continue the steps for conducting a strategy session with your employee:

4. Ask for the employee’s perspective on what the issue is

You can say, “I’d like your perspective on what the issue is and what is creating it.” In our example, others may find the employee difficult, but perhaps the others are being difficult to the employee. You don’t know, so provide ample space in the conversation for the employee to explain his or her perspective. You will likely get more robust information than you probably got from the “indirect” sources. The better the manager listens and understands the employee’s perspective, the more trust will be built between the employee and the manager. In many instances, the employee will fully admit to being “difficult” and will explain what their behavior was that would be interpreted as such. But the strategy session is about resolving the issue – not only the employee’s behavior. So make sure you get the employee’s perspective on what the issue is.

How to use strategy sessions as a way to manage indirect sources of info about your employees (part 1)

This is the first part of a three part series on how managers can use “strategy sessions” to improve the performance of their employees and their team, as well as the manager’s own performance.

Managers receive a lot of information about their employees from indirect sources – often much more information than from direct observation. I frequently write about how it is important that performance feedback be performed based on direct observation, or else it risks being non-specific and non-immediate, and generally becomes useless the less specific and less immediate it is.

However, managers are not often enough in the position to observe directly what it is the employee did exactly and provide this level of performance feedback. And with all of the indirect information floating around – such as from customers, other employees, bosses and metrics – it becomes difficult to figure out what to do about it.

Here’s an example I’ll use throughout this series: You are getting “feedback” from your employee’s peers and partners that he was “difficult” during a recent series of meetings. You’d like to give feedback on this. But what is it exactly that was “difficult” and why is this happening? And maybe this “difficult” behavior was actually a good thing? You really don’t know.

My recommendation is, instead of having a “feedback conversation”, have a “strategy sessions” with your employee. The idea with strategy sessions is that you partner with your employee to figure out the best course of action moving forward to address the “feedback” (actually, it’s an indirect source of information) and still achieve the goals. In short, you and your employee strategize together.

This is different from delivering corrective feedback, which is more direct, specific and immediate, with a clear course of behavioral actions that are different the next time it is performed. Strategy sessions are more along the lines of “What should we do to get the best outcome?”

Here are the first three steps on conducting strategy sessions with an employee: