Bonus! Three more tips for how manager can improve direct peer feedback

I’ve been writing a lot about peer feedback lately, and here’s why: It can do great things for your team, or it can do bad things for your team. So let’s get it right. Let’s make it a force for good, rather than bad.

In my previous article, I provided three tips for driving the positive outcomes of using peer feedback as a tool for improving your team performance. As a manager, you have to manage how peer feedback is given. If you manage this, your team as a whole will drive for improved performance, not just you.

Let’s continue down that path and explore three more tips for developing a team that uses peer feedback effectively:

4. Phase in giving feedback and who gives feedback

There are lots of situations where you must beware unleashing the feedback-giving ethos:

–A new team member may not be the best person to give feedback. The new team member may not know what the right course of action is. However, that person is also a candidate to receive peer feedback, and hence will begin to experience the culture of giving and receiving peer feedback. But when first starting, perhaps you should not unleash the expectation to give peer feedback right away.

–Similarly, another team member may have trouble using behavior-based language. Don’t encourage this person to give peer feedback.

Tips for how a manager can improve direct peer feedback

Peer feedback can be a tricky thing. When it is given indirectly, such as via 360 feedback surveys, it potentially makes a mess that is hard to clean up. But what about when peer feedback is directly given? There are pros and cons for peer feedback directly given, and perhaps the biggest argument in favor of direct peer feedback is that it multiplies the amount of performance feedback an employee receives.

Use these tips to encourage your team to maximize the pros and minimize the cons:

1. Get the team, in addition to the manager, good at giving feedback

The Manager by Design blog knows how badly given feedback can ruin so many things about the work environment. And there is an epidemic of badly-given feedback out there, and for this reason I have some hesitation to recommend in this post that the lines of feedback be increased, since it could be increased badly given feedback.

However, performance feedback is such an important performance driver that this must be overcome! There are ways to improve how you give feedback and can identify what good feedback looks like. This blog provides a number of tips on how to improve the feedback, from making it specific and immediate to using behavior-based language, to seeking direct observation and feedback opportunities. There are many examples of great training opportunities to learn how to give performance feedback. In the Seattle area, I recommend Responsive Management Systems, which provides services that will improve how you prepare to give feedback and give feedback that gets the results you want. Of particular interest related to this topic is their “Responsive Colleague” program.1

An opportunity to increase the amount of performance feedback on your team

Peer feedback is frequently given via indirect surveys, perhaps as part of a 360-degree feedback program. I would like to argue that this doesn’t really count as peer feedback, since it is time-delayed, indirect, and frequently non-actionable. I’m more in favor of direct peer feedback, since it is specific and immediate, can be focused on improving performance and teamwork. However, there are some reasons to be wary direct peer feedback, as I detail in my previous post.

However, the main reason I’m in favor of direct peer feedback is that it multiplies the amount of performance feedback that team members receive. Let me explain:

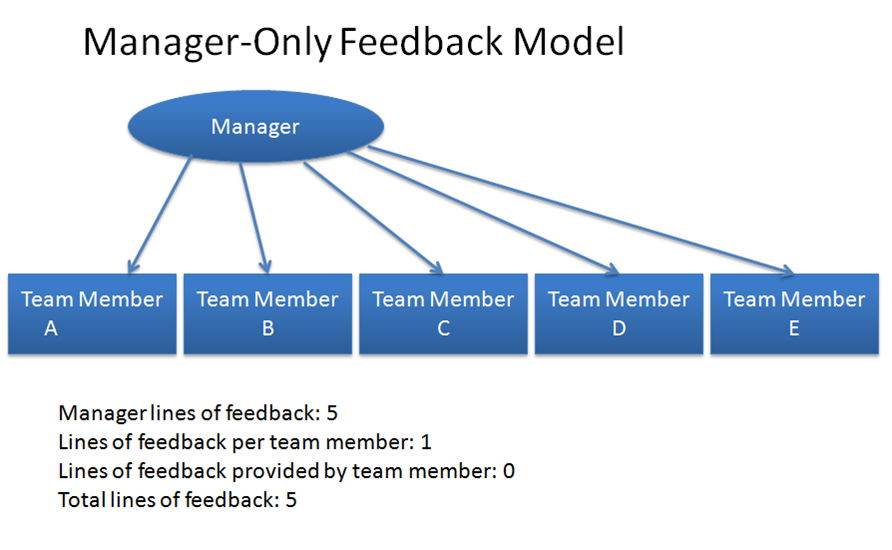

A traditional model for how employees improve their performance is through manager observation, and then the manager provides coaching and corrective feedback. For a team of five people, this is what it looks like:

Look familiar? This is the popular conception for how employees receive feedback on their performance. It is predicated on the belief that the manager has enough expertise in all the areas of the team performance to provide feedback, and the manager actually has the skill to provide feedback, which, alas, is not always the case. When most of us start a job, this is the general mental model that we have. After all, the manager is the one who evaluates our performance, and knows the expectations for performance! Employees expect to receive feedback from the manager on performance.

Some pros and cons of peer feedback directly given by peers

I’ve written articles lately about the risks of peer feedback from surveys and how peer feedback can be best utilized to improve performance on your team and in your organization. A frequent scenario is that the manager receives some sort of report with “360 feedback” from peers on team members’ performance. Then the implication is that the manager has to do something about it.

When the feedback comes from a survey, the feedback is indirect, and it’s of lower quality. The feedback is coming from a secondary source, there is also a serious time delay, the facts of the matter are usually murky and there is no alternative course of action offered. It’s also not clear if the person receiving the feedback actually did the wrong thing. Really, as far as feedback to improve performance is concerned, it’s kind of useless.

But what about the scenario when a peer gives feedback directly to another peer? Is this desirable?

For example, lets say you are working on a project and a peer consistently misses a deadline. The peer says, “You have missed the deadlines, and this is causing project delays. Is there a way you correct this?” That counts as peer feedback, and it isn’t waiting for a survey process.

Here are some reasons peer feedback directly given can be desirable:

–The feedback is more likely to be specific and immediately given

–The feedback is likely to have an alternate course of action

–The feedback is likely to comes from an expert on policies and best practices

–The feedback is not directly tainted by managerial power relations related to promotions and annual review toxicity

–The feedback is likely aimed at immediately improving performance of both the individual and the team

These are all excellent arguments in favor of peer feedback directly given, but there is another argument in favor of direct peer feedback.

How to use peer feedback from surveys for good (it’s not easy) – Part 2

This article is the second in a series on how managers can better use peer “feedback” from surveys. In general, a manager should be dubious about the quality of feedback that information provided on peer feedback surveys, since they are non-specific and time delayed. At best, this information provides clues and subtext for what is actually happening, and don’t reach the bar of performance feedback, but instead is general info. In the previous article, I discussed how managers should

- Treat the info as clues

- Stick to directly observed behaviors

- Ask for specific and immediate feedback from peers (instead of waiting for the survey to come around)

Today, I’d like to focus on using this information that the survey provides to understand the greater system that is driving the performance of your employees.

4. Use peer feedback as a basis for a strategy session with your employee

I’ve written before about how when giving performance feedback, isn’t always about the individual performance of an employee. Many times, peer feedback can reveal these systemic challenges with the job.

How to use peer feedback from surveys for good (it’s not easy) – Part 1

I’ve been writing a lot about peer feedback lately. What’s interesting is that peer feedback is often about the subtext of what happened between the peer and the employee. The manager looks deeply into the peer feedback to identify the hidden meaning of what the peer was getting at. But what about the thing above the subtext, the thing right there on the surface? What’s that called?

The text.

(Thanks to Whit Stillman’s Barcelona for help writing the opening of this article)

In this case, the text is the actual employee behavior, and this provides a clue for how managers should use peer feedback.

1. Treat peer feedback as clues, hidden meanings and shadowy innuendo

If you get a peer feedback report (often the result of some sort of “360 degree survey” conducted by the HR department), understand that this is a series of random snapshots into an employee’s behavior. Treat it as such. When the peer feedback says, “Jeremy is the greatest!” that means something good, but we’re not really sure. When the peer feedback says, “Jenny does so much to make this a strong team.” There’s something there about teamwork. It’s interesting, but we don’t really know what that means. When the peer feedback says, “Anthony never does any work.” This means that someone somewhere objects to Anthony’s performance. We’re not sure to what exactly this is referring, but there is something there, we think.

In other words, it is all unverified information, but it might give you some clues to something, or maybe not.

Why peer feedback from surveys doesn’t qualify as feedback

In a previous post, I identified peer feedback from 360 degree surveys as a source of inputs where a manager gets information about an employee’s performance. Peer feedback via 360 degree surveys has become increasingly popular as a way of identifying the better performers from the lesser performers. After all, teams should identify people who get great peer feedback, and do something about the team members who get poor peer feedback. The better the peer feedback, the better the employee, right? Well, maybe. Maybe not. Let’s talk about how peer feedback should be used, and not misused.

OK, peer feedback. As Demetri Martin would say, “This is a very important subject.”

First of all, by definition, peer feedback on surveys is, from the manager’s perspective, indirect reporting of an employee’s performance. The peer gives the feedback via some intermediary source (survey, email request, or, if requested, verbal discussion), and then that information gets interpreted as to what it means by the manager, or perhaps even some third party algorithm.

So it is essentially hearsay. Since it is one degree away from direct observation of performance, peer feedback is inherently more risky to use as a way to provide feedback on an employee’s performance. Here’s why:

The best feedback – or the most artful, as I like to say – has the following qualities, amongst others:

–It is specific

–It is immediate

–It is behavior-based

–It provides an alternative behavior

Let’s see how peer feedback stands up!

Specificity: Peer feedback on surveys comes in the form of a summary of behaviors over an aggregate period of time. Sample peer feedback will say something like, “John is always on top of everything, which I enjoy,” or “John needs to stop checking messages during the team meeting.” Now here’s the rub: This looks like general feedback, but it may be (you don’t know for sure) related to one incident. The “on top of everything” may refer to arranging a co-worker’s birthday party. The “check messages during a meeting” may have happened during the one meeting when his daughter was undergoing surgery. Or it could be something that John always does. You don’t know. It’s general or it’s specific. You don’t know.

Or. . .have you ever seen this kind of peer feedback?

“During the September 18 team meeting, John was checking his messages when he should have been working with the team to brainstorm solutions to resolving the budget shortfall. Then, on the September 25 team meeting, John received two phone calls during the meeting, interrupting the discussion flow about what our strategy for next year should be. Then, on October 2, John. . .”

This kind of peer feedback doesn’t happen on surveys. Instead, you get summaries of behaviors that may be based on a specific incident. . . or not. It may be work-related, or not. You don’t really know.