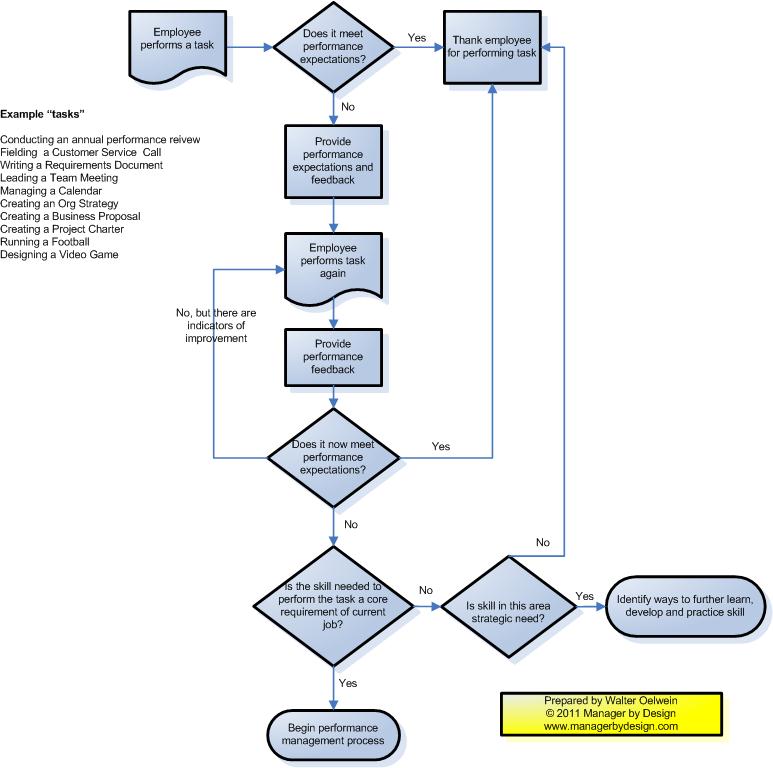

A Performance Feedback/Performance Management Flowchart

The Manager by Designsm blog seeks to create better managers by design. Here’s a great tool that outlines a simple flowchart of when a manager should provide performance feedback, and when the performance management process should occur. It can be used in many contexts, and provides a simple outline of what a manger’s role is in providing feedback, and how this fits with the performance management process (click for a larger image).

You’ll see that Performance Feedback starts at the task level, not the person level. You want to know what the task is, and make sure the individual gets feedback on how well he or she is performing the task. It also requires the manager to know what acceptable performance looks like. If not, then the manager is in a complex feedback situation, and both the manager and the employee agree to strategize on how to do the task differently, since it isn’t defined yet.

You’ll also notice that there is a lot of activity prior to the performance management process, which is actually a more formal version of this same flowchart. Managers need to perform this informal version first.

Let me know what you think. Do you your managers follow this flow chart? Do they skip steps? Do they add steps?

Related articles:

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

How to have a feedback conversation with an employee when the situation is complex

A tool to analyze the greater forces driving your employee’s performance

When an employee does something wrong, it’s not always about the person. It’s about the system, too.

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

What inputs should a manager provide performance feedback on?

When to provide performance feedback using direct observation: Practice sessions

When to provide performance feedback using direct observation: On the job

Five more markers and examples of what a good annual review looks like

In my previous article, I provided five markers of what a well-conducted annual review looks like. Let’s look at some more. It is possible to actually conduct an annual review well, but this is no guarantee. So let’s keep looking for those precious markers of a manager who knows how to use the annual review for good, rather than perpetuate it as a tool for suffering.

Marker #6: Improvement is germane to the discussion

If the annual review has any discussion about where the employee’s skills and performance was at the beginning of the year, and a comparative analysis at the end of the year – in those same skills – then this means that the manager is actually concerned with increasing the capability of the organization. I would consider this generally a good thing. For example:

“At the beginning of the year, we discussed how we can improve Alex’s presentation skills, as she frequently presents business partners. During the year Alex sought mentoring and feedback in this area, and the results show that this effort has paid off. Our partners have reported that they find her speaking style inviting and informative, and Alex has consistently been able to meet the objectives of the presentations.”

Marker #7: References to the goals

First, a marker would be that the employee and the team actually have some sort of goals. That would be the first marker of a good performance evaluation, as it provides something against which the manager evaluates the employee. Now, the second part of this is if the manager actually references the goals in making the evaluation.

“We had the ambitious goal at the beginning of the year to implement a new payroll system to further streamline what was before a highly labor-intensive project. Jeanine was a key part of the team that scoped the project, identified the goals of what success of the project was. Jeanine managed the vendor selection process, kept the team focused on the desired outcomes, and ensured that the team understood what was in scope and out of scope via her weekly communications. This was a key factor in assuring that the project stayed on track, which it did. The new payroll system was launched on time earlier this year, and has significantly reduced the processing time.”

Marker #8: Teamwork is referenced by both the employee and the manager

The individual performance review necessarily focuses on the individual. I consider this bad management design, as individual work is good, but teamwork can create greater outcomes. Almost all workgroups rely on teamwork. Managers and employees can transcend the design by invoking what teamwork happened during the review period. Let’s say that the manager talks about the great teamwork that the employee engaged in. Let’s say that the employee mentions how she contributed to building the team, and how she made an effort to improve the capability of the team, or looked out for the interest in the team. This would reflect that the manager and team are actually concerned with the power of teamwork over the expectation for an individual to perform independently of teamwork. Here’s an example:

“Jonathan demonstrated that he is an excellent team player by creating a process document that showed how to complete a task that many team members performed irregularly. This helped the team gain some efficiencies, and inspired other team members to make similar efforts. The team is healthier as a result of Jonathan’s efforts.”

Marker #9: Goals seem to have a similar voice and scope across team members

Many annual reviews have a section where the employee’s goals are documented. One could look at the goals of all the team members across a managers’ team. Imagine, if you will, goals that seem to have a similar tone, similar metrics, and similar scope across team members. They don’t have to be exactly the same, because not all roles are the same, but if the goals are all striving toward a similar metric or output, this demonstrates that the manager knows what the team is striving to do, and has actually infused it in the goals. When the goals seem to be similarly written, we also know that the manager has provided input and perhaps even co-authored the goals – or this is sometimes tough to imaging – this was done as a group. Too many times we see managers push down the goal writing process to the individual employees, which results in, by definition, different looking goals. Let’s celebrate those times when we see goals across the team show some kind of consistency across the team.

Marker #10: There is agreement between the employee and the manager

If a manager and employee seem to say that they agree about things on the performance review, this reveals that the employee and the manager actually talked about these things prior to the annual review. Differences in what the results were, what the impact of the employee’s actions and whether or not the employee performed at a high level – well these were resolved external to the review, as should be the case. Many managers wait until the review to resolve lingering disagreements, sometimes even using the review to create new ones, but those managers who seek alignment and understanding with their employees throughout the year, and don’t wait until the end of the year should be recognized as superior managers. Here’s what alignment looks like:

Employee: “I increased sales by 15% through my efforts to reach out to a new customer base.”

Manager: “I agree with the employee. He was effective at identifying a new target market, and then executing the strategy of accessing the market.”

See? no debate! Do you think that a debate might have happened during the year to get to this agreement of what the employee’s efforts were and what were the estimated results? Yes. Does it appear on the annual review? No, but the agreement of the results of the discussions do appear.

We should celebrate when managers do a great job on the perilous annual performance review, and do whatever we can to increase the chances of a well-conducted review.

Have you seen these markers of success on a review? Let’s hear your stories!

Related Articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

How to neutralize in advance the annual toxic performance review

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

Performance Feedback is about next time

Here’s a scenario: Jim reacts badly to a new change in the organization. He starts telling all of his co-workers how much he doesn’t like the change, and discusses ways to undermine or avoid the change. This causes increased doubt in the change, and even causes confusion as to whether the change is actually going to happen.

Jim manager has the option of either addressing or ignoring Jim’s reaction. If the manager addresses it, this would be a performance feedback conversation.

However, many managers avoid the performance feedback conversation. One reason for this is the manager may believe that Jim’s behavior on the job is deeply embedded in the employee’s personality, and the employee’s actions are innate to their very being. So a basic thesis emerges that “Jim is just like that.” There is the belief that Jim just won’t change. So no performance feedback conversation is necessary.

But this is an untested thesis. Jim did react badly to the news, but does this mean that he has to react the same way next time? The answer is—you don’t know until you have the performance feedback conversation.

If you don’t have the performance feedback conversation, the Jim will definitely behave in the exact same way should a similar set of circumstances occur. His behavior was “negatively reinforced,” meaning that he received no information that his behavior was incorrect and he received no adverse reaction from his manager. In fact, his behavior may have also been “positively reinforced” when the other employees start agreeing with his arguments about how he doesn’t like the change. The manager, by being silent, is letting the other forces of behavior determine Jim’s behavior in the workplace.

So the basic thesis that Jim “always is like that” only is true if he never receives coaching or feedback on what he should do instead. And when the manager does not step in, then for sure this thesis will be proven correct.

The Art of Providing Feedback: Banish the use of “always”

Here’s a tip for managers: Banish the word “always” from your vocabulary.

The Manager by Design blog frequently writes about how to give performance feedback. Performance feedback is an important skill for any manager, as it is one of the quickest ways to improve performance of individuals on your team.

One particularly useless word in the art of performance feedback is the word “always.” Here are some examples of where a manager mistakenly uses “always” in performance feedback:

You’re always late

You always make bad decisions

You always come up short

These are examples of bad performance feedback, since they are not behavior-based, but the word that makes these examples particularly bad is the word “always.” That’s because “always” implies that the employee’s performance is eternal and permanent. And that undermines the whole point of performance feedback, which is to change the way your employees are performing, and have them do something better instead.

Let’s start by removing the word always from the three examples above:

You’re late

You made a bad decision

You came up short

OK, these are still pretty bad, but at least this feedback didn’t put an eternal and permanent brand on the employee as “always late,” “always bad at making decisions,” and “always underperforming.” At least without the word “always”, the feedback is isolated to the once incident, making it possible for the feedback to be more specific and immediate.

Removing the word “always” allows you to focus on the particular event you are giving feedback on, and not make a generalization about the person’s permanent character.

Removing the word “always” allows you to support the thesis about “late” “bad decisions” and “coming up short” with more details. By discussing the details, you at least have entry to discussion as to why this happened, and identify the forces that went into the performance.

Removing the word “always” implies that this bad event can be turned around and the next time the performance can be improved.

When you use the word “always” in a feedback conversation, it implies that there is a permanence to the employee behavior the manager is ostensibly trying to correct. “Always” makes the performance feedback conversation useless, because instead of trying to get the employee to do something differently next time (be on time, make a good decision, meet the goal), it instead sounds like a relegation or banishment to permanent underperformance that the employee can never get out of.

That’s not good for either the manager or the employee, unless you want a chronically underperforming team that hates the manager.

Finally, by saying someone is “always late” or “always makes poor decisions”, it is inherently incorrect. If that employee can find one time he was on time, or one time she made a correct decision, then the manager is proven wrong. Not a good move if you want to be able to lead a team.

So to all of the managers out there – banish the word “always” from your vocabulary.

Have you ever been told that you “always” do something? What was that like?

Related articles:

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

An example of giving specific and immediate feedback and a frightening look into the alternatives

Examples of when to offer thanks and when to offer praise

What inputs should a manager provide performance feedback on?

Getting started on a performance log – stick with the praise

An example of how to use a log to track performance of an employee

Providing corrective feedback: Trend toward tendencies instead of absolutes

Behavior-based language primer for managers: How to tell if you are using behavior-based language

Behavior-based language primer for managers: Avoid using value judgments

Behavior-based language primer for managers: Stop using generalizations

How to be collaborative rather than combative with your employees – and make annual reviews go SOOO much better

Many managers botch the annual review process. There’s this persistent idea out there that the manager needs to provide “one good thing, one bad thing” on an annual performance review. However unlikely it is that the employee does an equal amount of damage as good over the course of the year, this model seems to persist. Many times, managers will actually go fishing for incidents that are bad. They’ll try to find those moments where the employee said something wrong, missed a step, or caused friction on the team. The manager will fastidiously wait for the annual review and then spring it upon the employee – Aha! You did this bad thing during the year! And I get to cite it on the review.

Well no more of that!

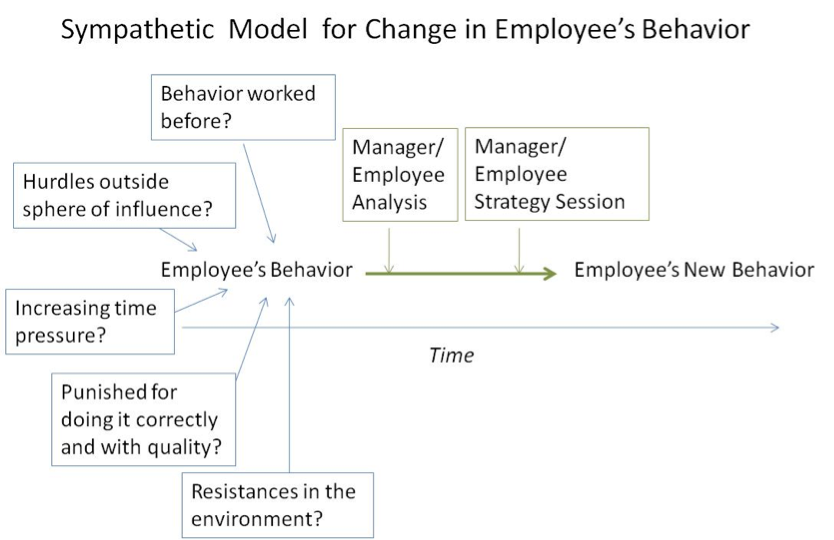

I propose the sympathetic model of performance feedback. In the sympathetic model, the manager looks at both the individual and the system in determining what the employee ought to have done differently (if anything) and what ought to be done differently in the future.

Here is the sympathetic model: (Click for larger image)

When you look at an employee’s actions this way, you can see that there may be some greater forces that went into the employee’s behavior. So instead of using a bad incident to cite what is wrong with the employee, the sympathetic model asks that managers engage in analysis and discussion with the employee to figure out what drove the behavior. Then the manager and the employee strategize on what to do next, and what should be done in the future.

Bonus! Three more tips for how manager can improve direct peer feedback

I’ve been writing a lot about peer feedback lately, and here’s why: It can do great things for your team, or it can do bad things for your team. So let’s get it right. Let’s make it a force for good, rather than bad.

In my previous article, I provided three tips for driving the positive outcomes of using peer feedback as a tool for improving your team performance. As a manager, you have to manage how peer feedback is given. If you manage this, your team as a whole will drive for improved performance, not just you.

Let’s continue down that path and explore three more tips for developing a team that uses peer feedback effectively:

4. Phase in giving feedback and who gives feedback

There are lots of situations where you must beware unleashing the feedback-giving ethos:

–A new team member may not be the best person to give feedback. The new team member may not know what the right course of action is. However, that person is also a candidate to receive peer feedback, and hence will begin to experience the culture of giving and receiving peer feedback. But when first starting, perhaps you should not unleash the expectation to give peer feedback right away.

–Similarly, another team member may have trouble using behavior-based language. Don’t encourage this person to give peer feedback.

How to use peer feedback from surveys for good (it’s not easy) – Part 2

This article is the second in a series on how managers can better use peer “feedback” from surveys. In general, a manager should be dubious about the quality of feedback that information provided on peer feedback surveys, since they are non-specific and time delayed. At best, this information provides clues and subtext for what is actually happening, and don’t reach the bar of performance feedback, but instead is general info. In the previous article, I discussed how managers should

- Treat the info as clues

- Stick to directly observed behaviors

- Ask for specific and immediate feedback from peers (instead of waiting for the survey to come around)

Today, I’d like to focus on using this information that the survey provides to understand the greater system that is driving the performance of your employees.

4. Use peer feedback as a basis for a strategy session with your employee

I’ve written before about how when giving performance feedback, isn’t always about the individual performance of an employee. Many times, peer feedback can reveal these systemic challenges with the job.

How to use peer feedback from surveys for good (it’s not easy) – Part 1

I’ve been writing a lot about peer feedback lately. What’s interesting is that peer feedback is often about the subtext of what happened between the peer and the employee. The manager looks deeply into the peer feedback to identify the hidden meaning of what the peer was getting at. But what about the thing above the subtext, the thing right there on the surface? What’s that called?

The text.

(Thanks to Whit Stillman’s Barcelona for help writing the opening of this article)

In this case, the text is the actual employee behavior, and this provides a clue for how managers should use peer feedback.

1. Treat peer feedback as clues, hidden meanings and shadowy innuendo

If you get a peer feedback report (often the result of some sort of “360 degree survey” conducted by the HR department), understand that this is a series of random snapshots into an employee’s behavior. Treat it as such. When the peer feedback says, “Jeremy is the greatest!” that means something good, but we’re not really sure. When the peer feedback says, “Jenny does so much to make this a strong team.” There’s something there about teamwork. It’s interesting, but we don’t really know what that means. When the peer feedback says, “Anthony never does any work.” This means that someone somewhere objects to Anthony’s performance. We’re not sure to what exactly this is referring, but there is something there, we think.

In other words, it is all unverified information, but it might give you some clues to something, or maybe not.

Why peer feedback from surveys doesn’t qualify as feedback

In a previous post, I identified peer feedback from 360 degree surveys as a source of inputs where a manager gets information about an employee’s performance. Peer feedback via 360 degree surveys has become increasingly popular as a way of identifying the better performers from the lesser performers. After all, teams should identify people who get great peer feedback, and do something about the team members who get poor peer feedback. The better the peer feedback, the better the employee, right? Well, maybe. Maybe not. Let’s talk about how peer feedback should be used, and not misused.

OK, peer feedback. As Demetri Martin would say, “This is a very important subject.”

First of all, by definition, peer feedback on surveys is, from the manager’s perspective, indirect reporting of an employee’s performance. The peer gives the feedback via some intermediary source (survey, email request, or, if requested, verbal discussion), and then that information gets interpreted as to what it means by the manager, or perhaps even some third party algorithm.

So it is essentially hearsay. Since it is one degree away from direct observation of performance, peer feedback is inherently more risky to use as a way to provide feedback on an employee’s performance. Here’s why:

The best feedback – or the most artful, as I like to say – has the following qualities, amongst others:

–It is specific

–It is immediate

–It is behavior-based

–It provides an alternative behavior

Let’s see how peer feedback stands up!

Specificity: Peer feedback on surveys comes in the form of a summary of behaviors over an aggregate period of time. Sample peer feedback will say something like, “John is always on top of everything, which I enjoy,” or “John needs to stop checking messages during the team meeting.” Now here’s the rub: This looks like general feedback, but it may be (you don’t know for sure) related to one incident. The “on top of everything” may refer to arranging a co-worker’s birthday party. The “check messages during a meeting” may have happened during the one meeting when his daughter was undergoing surgery. Or it could be something that John always does. You don’t know. It’s general or it’s specific. You don’t know.

Or. . .have you ever seen this kind of peer feedback?

“During the September 18 team meeting, John was checking his messages when he should have been working with the team to brainstorm solutions to resolving the budget shortfall. Then, on the September 25 team meeting, John received two phone calls during the meeting, interrupting the discussion flow about what our strategy for next year should be. Then, on October 2, John. . .”

This kind of peer feedback doesn’t happen on surveys. Instead, you get summaries of behaviors that may be based on a specific incident. . . or not. It may be work-related, or not. You don’t really know.