Putting out fires: Managers who “want it now” or “want it yesterday” are managing from a deficit

Have you ever had a manager who has a last minute request, “I need this now!” The more extreme version of this is, “I need this yesterday.” Usually, this is a new last-minute request, and this can be very disruptive and annoying to employees, and a sure sign that the manager is “managing from a deficit.”

Now, I’m not talking about jobs where there is a last-minute nature to the job. A firefighter’s job, is, by definition, a “last-minute” kind of job. The firefighter’s boss will no doubt say, “We need to do this right away!” But there is a lot of preparation that firefighters engage in – with the aid and coordination of their bosses — that goes into meeting the demands of that “last minute” request known as a fire.

I’m talking about a boss who interrupts your job to request something new, and it is needed soon. And this request is made with urgency, perhaps with some yelling involved. These are requests that are metaphoric fires, not actual fires.

So if you are someone on a team that seems to have a lot of “fires”, then read on.

Let’s take a look at some of the sources of these last minute requests (a.k.a., fires):

1. Is the request primarily to assure the manager looks better to his manager?

A common source of this kind of last minute request is to provide assistance to the manager in helping him report up to his manager what is going on, most likely the request of the manager above her. So, ironically, the request keeps rolling downhill. If you have an organization with more than three levels, you have at least three “sources” for needs for updates. If the upper management team does this consistently, such last-minute requests can start to appear to be the norm. For example, let’s say that the upper management decides to schedule an “all team meeting” and wants all of managers in the group need to present to the team. And it’s going to happen next week. Last minute request spawned!

So the team needs to stop what they are doing and instead create a report on what they are doing. When this happens, the manager is asking the team to take the “hit” and not the manager. The manager should have the option to say to his manager, “This would disrupt my team in achieving its goals, which have already been prioritized” and provide the level of reporting already agreed upon. The request can be made to add it to future reports, as part of the core team deliverables. The manager can choose to make an exception and start the “metaphorical” fire, but should also note this as an opportunity to renegotiate what reporting –and the timing of it– the upper management needs. Read more

Performance feedback must be related to a performance

Have you ever received performance feedback about what you say and do in a 1:1 meeting?

Have you ever received performance feedback about your contributions to a team meeting?

Have you ever received performance feedback about not attending a team event or party?

Were you frustrated about this? I would be. Here’s why:

The performance feedback is about your interactions with your manager and not about what you are doing on the job. This is an all-too-common phenomenon.

If you are getting feedback about items external to your job expectations, but not external to your relationship with your boss, you aren’t receiving performance feedback. You’re receiving feedback on how you interact with your boss. The “performance” that is important is deferred/differed from your job performance, and into a new zone of performance – your “performance in front of your boss.”

OK, so now you have two jobs. 1. Your job and 2. Your “performance in front of your boss.”

Examples of how peer feedback from surveys is misused by managers

In my previous post, I describe how peer feedback from 360 degree surveys is not really feedback at all. At best, it can be considered, “general input from peers about an employee.” Alas, it is called peer feedback, and as such, it risks being misused by managers. Let’s talk about these misuses:

As a proxy for direct observations: Peer feedback is so seductive because it sounds like something that can replace what a manager is supposed to be doing as a manager. One job of the manager is to provide feedback on job performance and coach the employee to better performance. However, with peer feedback from surveys, you get this proxy for that job expectation: The peers do it via peer feedback. Even better, it is usually performed by the Human Resources department, which sends out the survey, compiles it, and gives it to the manager. Now all the manager has to do is provide that feedback to the employee. See, the manager has given feedback to the employee on job performance. Done!

Never mind that this feedback doesn’t qualify as performance feedback, may-or-may not be job related, or may-or-may not be accurate.

The incident that sticks and replicates: Let’s say in August an employee, Jacqueline, was out on vacation for three weeks. During that time, a request from the team Admin came out to provide the asset number of the computer, but Jacqueline didn’t reply to this. And worse, Jacqueline didn’t reply to it after returning from vacation, figuring that the admin would have followed up on the gaps that remained on the asset list. Then it comes back a year later on Jacqueline’s peer feedback that the she is unresponsive, difficult to get a hold of and doesn’t follow procedures. This came from the trusted Admin source!

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

Today I want to talk about a management team and how it relates to employees. Imagine the management team. They are in charge of the project of evaluating the performance of their collective employees. In some organizations, they are asked to “stack rank” all employees in an organization, or at least put them in general categories, such as low performer, average performer, high performer, or some variation like, “Needs improvement” at the bottom of the rank to “High Potential” at the top of the rank.

OK, now the management team needs to do the work of ranking the employees. The person facilitating this process is likely to be the manager of the team of managers, or the manager above that. So you have a bunch of managers in a room discussing a large batch of employees’ performance, making arguments about who is a good performer, who is an average performer and who is a low performer. Oftentimes there is a forced curve that requires some people into the “needs improvement” bucket. Oftentimes these discussions have promotion implications and bonus implications. In the examples of companies that have adopted the “fire the lowest 10%” philosophy, it also has firing implications.

Inevitably, the employees know that this kind of thing is happening between the managers. This is a common practice at many large organizations, and a tough one to get right. I’m not really sure it is possible to get right, and here’s why.

In a discussion like this, each manager is armed with some data about the employee. As discussed frequently in this blog, that data about how an employee performed is limited at best, and non-existent at worst.

There are cases where there are specific metrics that are directly comparable across employees, and a certain amount of fairness can be achieved by this measure. This typically occurs with employees at the lower level of an organization, and if you have several employees doing similar or repetitive work that produces comparable metrics. This is decreasingly the case, however, as even – or especially — entry-level positions require more quality-minded, customer-oriented, problem-solving type thinking to achieve high-pressure work goals. So even when there are directly comparable metrics, there are many intangibles that come into play.

So inevitably, it seems that current management design requires that managers get in a room and essentially argue who is the best employee, whether they deserve a raise, and, in many cases, argue that the other employees are less deserving.

Now, what’s tough is that these decisions are way out of the employee’s control – even if they have done amazing work through the year.

Here’s why:

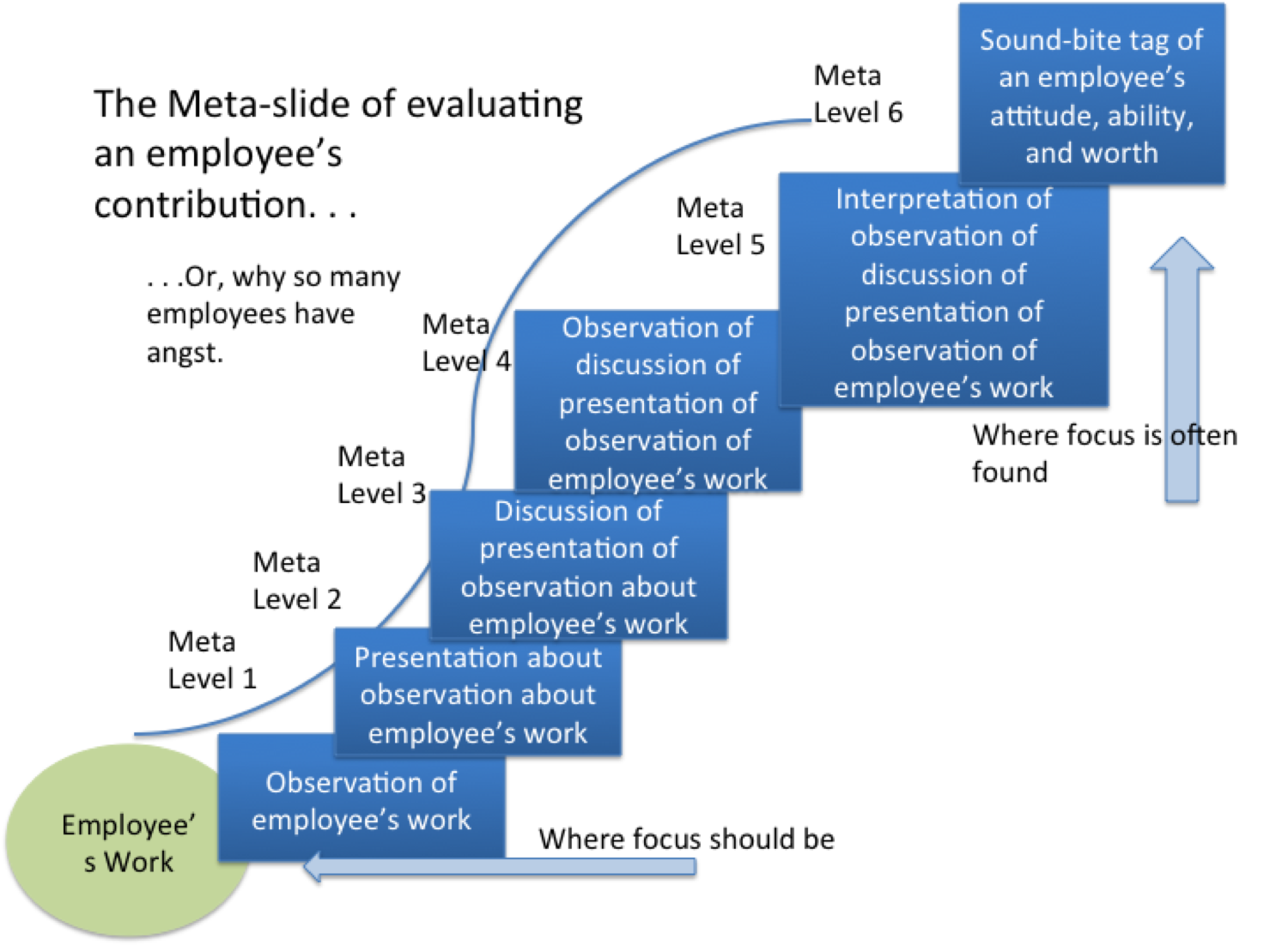

The discussion is inevitably a summary statement of everything an employee has done through the year, and that summary statement cannot possibly be true. In the “stack rank” discussion, a certain amount of meta-analysis of the employee’s performance and worth is required. Here’s what I mean:

Let’s clarify what “dealing with ambiguity” means

Managers should help bring clarity to their team and make decisions on the best available information. That is a key role of managers. But somehow this gets lost. Let’s look at the concept of “dealing with ambiguity” and see how this can happen:

In many work environments, one of the key competencies managers and employees are expected to have is “dealing with ambiguity.” For example, if you look at Microsoft’s education competencies (listed here), “dealing with ambiguity” is defined as follows:

Dealing with Ambiguity: Can effectively cope with change; can shift gears comfortably; can decide and act without having the total picture; can comfortably handle risk and uncertainty.

With this definition, it appears that one who “deals with ambiguity” could be someone who accepts the ongoing state of ambiguity. That is, “dealing with ambiguity” means “living such that ambiguous things stayed ambiguous.” Or in other words, “Keep things ambiguous—that’s OK.”

Nowhere in the description of this competency, surprisingly, is the ongoing effort to reduce ambiguity.

A change agent brought in from the outside needs more than being a change agent from the outside

In my previous post, I explored the management “design” of hiring someone from a successful organization to bring change to your org. It’s a great idea – hire from the best, and you get the best. And presumably, this person is a top performer. Win-win! However, this can be a perilous design, as the organization you’re hiring from perhaps created great performance through the org processes and culture. The success was not necessarily via the individual’s greatness, but from the collective efforts of the previous org. But that’s what you’re hiring for when you hire this kind of expertise – change and improvement. So you need to be committed to it.

Let’s imagine that you hire a change agent who is ready to bring in the successful ideas and practices of the prior org to the new org. What more needs to be done to help this change agent be successful? Let’s take a look. Read more

Bonus! Five more reasons why discussing weaknesses with employees is absurd and damaging

In my previous post, I described five reasons discussing weaknesses with an employee often seems so awkward, despite the best intentions. Yet, managers are frequently asked to do so on an employee’s annual review form, which, by design, creates some unnecessary and damaging conversations. Here are five more reasons discussing weaknesses with employees fails: Read more

Five reasons why focusing on weaknesses with employees is absurd and damaging

Many managers are asked to discuss with their employees the various strengths and weaknesses of the employee. This often backfires, as the employee is appropriately suspicious of the manager’s intent when discussing “weaknesses”. The reason: This will appear on the employee’s annual performance review, and becomes part of the employee’s “brand” going forward – even if the weaknesses are irrelevant or nonsensical. As a result, any discussion about an employee’s weaknesses should be for the purpose of identifying and planning strategic needs of the organization. Instead what happens more often than not is that a discussion of an employee’s weaknesses is performed simply to document bad things about an employee. But why would you want to do that? You don’t. And here’s why not: Read more

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

A mistaken notion that many managers have is the belief that on a performance review they need to comment on and provide examples of both the good things and the bad things that an employee did over the course of the review period. This is sometimes taken to the next level, where the manager says one good thing and one bad thing about each area of the employee’s performance.

Here’s an example of something a high performer might see on a review:

Jeff exceeded sales expectations by 15%, placing him in the top 10% of the sales force. Jeff was below expectations in submitting his weekly status reports on time, and the reports he did submit were wordy.

This is a mistake and this practice should be stopped.