What a manager can do if the big boss puts a tag on an employee

In my previous post, I described a common scenario and the mess it makes:

An employee meets with the big boss (the manager’s manager) in what is often called a “skip level” one-on-one. Or the big boss sees – or hears about — some output of an employee, representing a small fraction of the employee’s output. The big boss then makes a judgment on the employee – what I call a “tag” on the employee. That tag now sticks on the employee. It creates a big mess that puts the manager in a bind – how do you address this employee’s tag?

Here are tips for what the manager caught in the middle can do to handle the tag – whether good or bad.

1. Keep the tag in mind and wait for observed behaviors that are consistent with “the tag”

Ok, if the manager’s manager (“big boss”) is so keen at identifying employee’s essence and value, then surely there will be plenty of opportunities to observe directly the performance of the employee that has earned that tag. Whether the tag is “negative attitude” or “rock star”, the manager needs to wait for opportunities to see behaviors that fit with this tag, and correct those behaviors.

If the manager is keeping a performance log on the employee, these trends should manifest if they are correct, and fail to appear should they be incorrect.

2. Ignore what your manager says and do your job of managing

Almost the same as the point above, but subtly different. It doesn’t matter what the boss’s boss says. If you are managing your employee, work with your employee to make sure he meets performance expectations, provide feedback that drives to the desired behaviors, then, if the employee is performing the job duties according to expectations, then it kind of doesn’t matter what the boss’s boss says. Your assessment is based on better data and you can justify it.

What to do when your boss gives feedback on your employee? That’s a tough one, so let’s try to unwind this mess.

Here’s the scenario:

Your employee meets with your boss for a “skip level” meeting. After the meeting, the employee’s boss’s boss (your boss) tells you what a sharp employee you have.

Or, let’s say that your boss tells you that your employee needs to “change his attitude” and “has concerns about your employee.” This is very direct feedback about the employee, and it comes from an excellent authority (your boss), and if you disagree with it, you disagree with your boss.

But this information is entirely suspect. Whether the feedback from the “big boss” is positive or negative, the only thing it reveals is how the employee performed during the meeting with the boss. And unless your employee’s job duty is to meet with your boss, it actually has nothing to do with the expected performance on the job. So if the feedback is negative, do you spend time trying to correct your employee’s behavior during the time the employee meets with the big boss, when it isn’t related to the employee’s job duties?

In addition, the big boss often prides him or herself on the ability to cut through things and come to conclusions quickly, succinctly, and immediately. The big boss will come to a conclusion about the employee based on the data provided in the one-on-one meeting, and will expect this conclusion to be corroborated by you and everyone else.

The big boss, in this process, will put a tag on the employee, whatever it is. Here are some examples of tags:

Up-and-comer

Introverted

Not a go-getter

Whip-smart

Not aware of the issues

Could be a problem

. . .or, the dreaded, ambiguous, “I’m not sure about him.”

What’s worse, since the “tag” originated with the big boss, it will likely stick.

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

Today I want to talk about a management team and how it relates to employees. Imagine the management team. They are in charge of the project of evaluating the performance of their collective employees. In some organizations, they are asked to “stack rank” all employees in an organization, or at least put them in general categories, such as low performer, average performer, high performer, or some variation like, “Needs improvement” at the bottom of the rank to “High Potential” at the top of the rank.

OK, now the management team needs to do the work of ranking the employees. The person facilitating this process is likely to be the manager of the team of managers, or the manager above that. So you have a bunch of managers in a room discussing a large batch of employees’ performance, making arguments about who is a good performer, who is an average performer and who is a low performer. Oftentimes there is a forced curve that requires some people into the “needs improvement” bucket. Oftentimes these discussions have promotion implications and bonus implications. In the examples of companies that have adopted the “fire the lowest 10%” philosophy, it also has firing implications.

Inevitably, the employees know that this kind of thing is happening between the managers. This is a common practice at many large organizations, and a tough one to get right. I’m not really sure it is possible to get right, and here’s why.

In a discussion like this, each manager is armed with some data about the employee. As discussed frequently in this blog, that data about how an employee performed is limited at best, and non-existent at worst.

There are cases where there are specific metrics that are directly comparable across employees, and a certain amount of fairness can be achieved by this measure. This typically occurs with employees at the lower level of an organization, and if you have several employees doing similar or repetitive work that produces comparable metrics. This is decreasingly the case, however, as even – or especially — entry-level positions require more quality-minded, customer-oriented, problem-solving type thinking to achieve high-pressure work goals. So even when there are directly comparable metrics, there are many intangibles that come into play.

So inevitably, it seems that current management design requires that managers get in a room and essentially argue who is the best employee, whether they deserve a raise, and, in many cases, argue that the other employees are less deserving.

Now, what’s tough is that these decisions are way out of the employee’s control – even if they have done amazing work through the year.

Here’s why:

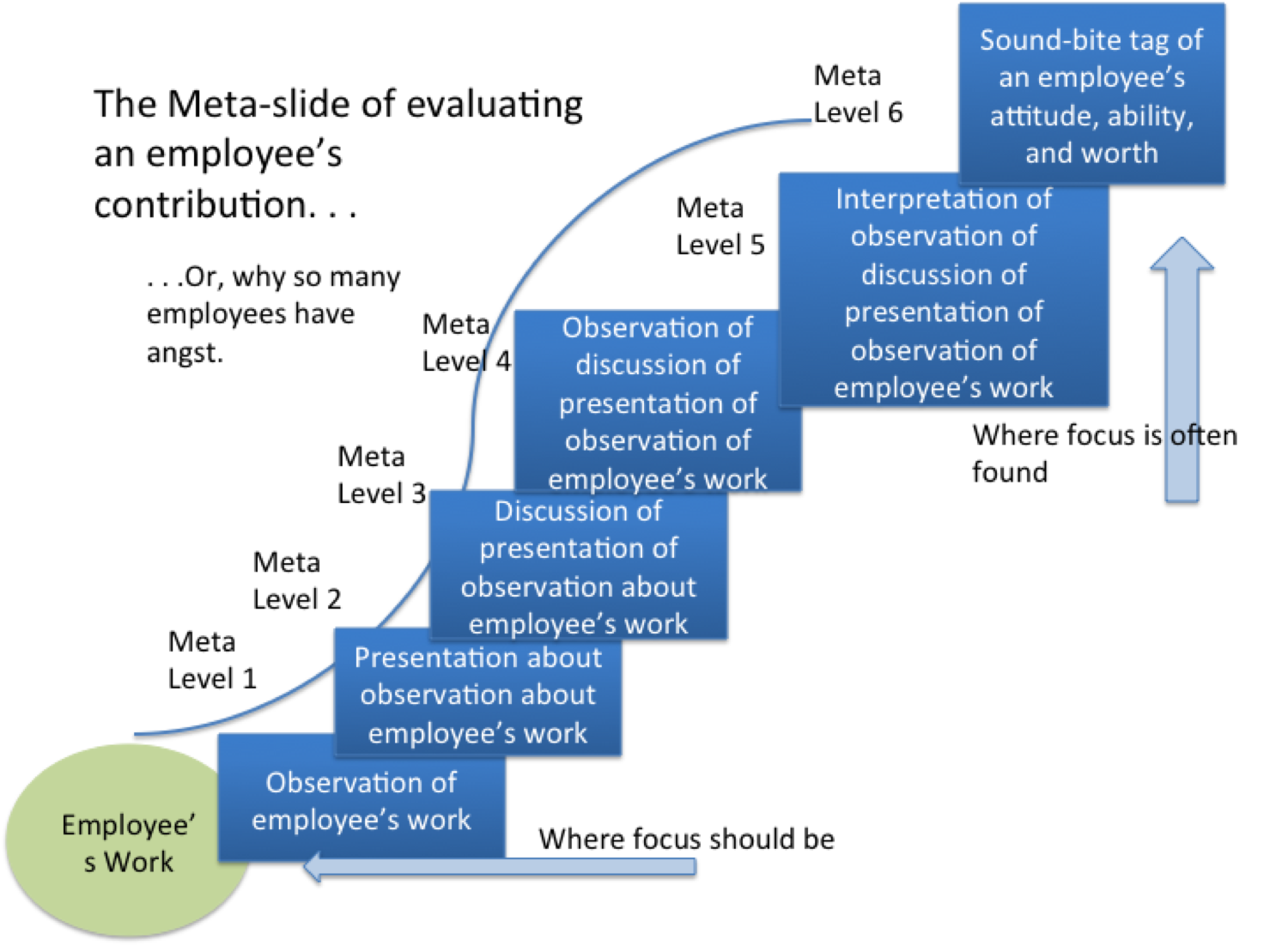

The discussion is inevitably a summary statement of everything an employee has done through the year, and that summary statement cannot possibly be true. In the “stack rank” discussion, a certain amount of meta-analysis of the employee’s performance and worth is required. Here’s what I mean: