Strive toward strategic placement of employees based on organizational need

In my previous post, I discussed how it takes a lot to compare and stack rank employees, and really the best you can do is to come up with some limited scenarios where you compare similar jobs, with clear rules, consistent evaluators and transparency. With that done, you now have determined the winner in a limited context in a given time frame. So it doesn’t really tell you who is the “best”, but who was the best in that context. If that context comes up a lot, then you can get trends and be more predictive, such as the case in answering “who is the best athlete,” but still leaves a lot open for debate. In the contemporary workplace, these conditions happen less and less.

In the contemporary workplace, employees are asked to adapt to constantly shifting situations, new technologies, new projects, and new skill sets. Instead of who is the “best” at something, it is the who is the “best” at adapting to new situations, which can go in many different directions. You need people who are great in different facets of the work, and who can adapt and improve and strive toward meeting the organizational goals. This makes it very unlikely that you can have some sort of conclusion who is the “best” and who is “on top”, since there is a diversity of skill sets needed to achieve these goals, and they are often shifting.

So instead of “stack ranking” employees, which implies that one employee is inherently better than another (and makes a not-so-subtle argument that it is forever that way), managers need to strategically place employees in roles and projects based on what the managers and employees assess they are good at and their ability to execute. It’s less about who’s the best, and more about what is the best placement to get the work done.

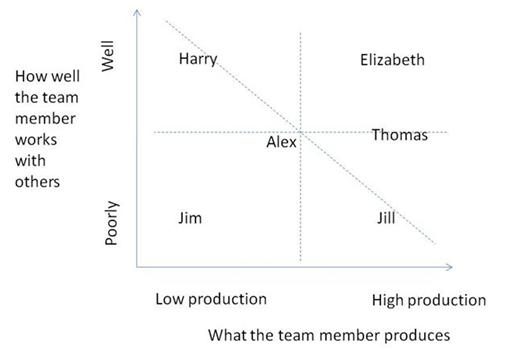

Let’s take a look at the What/How grid to be as a way to be more strategic with a team’s strengths. This grid shows an analysis by a manager of a fictional team, based on “what” the team member produces and “how” they work with others. Other analyses could be performed based on your organizational needs.

In this grid, the manager has assessed that Elizabeth and Thomas as skilled in both productivity and ability to work with others. But the manager also has Harry who seems to get along with lots of people, but doesn’t produce much, and Jill who seems to work really hard but isn’t as focused on relationships. So now the manager, instead of saying, “Elizabeth and Thomas are my top performers”, the manager should say, “What can I do with this group to get the most out of my team?”

I’d put Harry in a role that requires relationships to be forged. I’d make sure I’d give Harry some expectations for what we are looking to get out of those relationships (new leads? sales? higher customer satisfaction? socializing a new program across groups?) and rate him against these expectations. I’d put Jill in a role that is not customer-facing but requires a lot of work output where relationships are less crucial for success, and rate her against what she produces (and diminishing the importance of “how” she produces). Ideally, this most likely feeds to Harry information that makes him better. If I need more customer-facing work and relationship building, I’d put Elizabeth on that, and if I need more work output, I’d put Thomas and Elizabeth at that.

Elizabeth and Thomas are more flexible, which obviously has value, but if the value of customer relationship building is super-important for the team, then perhaps Harry is more valuable than Thomas for now. It isn’t a permanent thing, but a thing that is based on the context of the team’s needs, and not on the context of the employees inherent abilities.

With Alex, I would try to figure out where Alex is most likely to be needed in the near future, and work on giving performance feedback and coaching in the direction where your team is likely to need it. Perhaps Alex can be a back-up to Harry in the follow-up with customers.

With Jim, he rates lowly in two dimensions, which looks like a net-negative to the team, so I would look at the performance management process for him, because it doesn’t look like he’s helping the team at all, and unless he improves (which is entirely possible with the performance management process) there is likely someone else out there who could do his job better.

So instead of saying, “Elizabeth and Thomas” are the most important employees, the manager should first focus on trying to maximize where all employees can most help the team to achieve its goals. This treats all employees as valuable, and is likelier to achieve overall team performance.

This is where the management energy should be spent first and foremost. The shifting dynamics of the team context should be the greater concern, not the ranking of individual employees against one another, since you need the entire team to perform to be successful.

Also note that once placed on this grid, the people are not permanently located there. Any one of them can shift around based on changing circumstances, work stresses and pressures, and individual development.

In this article, I use a very simple “What/How” grid to identify the strengths of the team and to assist with illustrating how a manager can use this simple tool. Another common method is to use the Strength Finder tool from the book Now, Discover Your Strengths, which has many more dimensions and areas of insights and one I would highly recommend any manager do to identify the areas of strengths on the team and then make strategic decisions accordingly.

How much energy does your management team spend in strategically utilizing employee strengths? How does this compare to the amount of time ranking employees?

Related Articles:

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

An obsession with talent could be a sign of a lack of obsession with the system

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

How to use the What-How grid to build team strength, strategy and performance

Bonus! Three more tips for how manager can improve direct peer feedback

I’ve been writing a lot about peer feedback lately, and here’s why: It can do great things for your team, or it can do bad things for your team. So let’s get it right. Let’s make it a force for good, rather than bad.

In my previous article, I provided three tips for driving the positive outcomes of using peer feedback as a tool for improving your team performance. As a manager, you have to manage how peer feedback is given. If you manage this, your team as a whole will drive for improved performance, not just you.

Let’s continue down that path and explore three more tips for developing a team that uses peer feedback effectively:

4. Phase in giving feedback and who gives feedback

There are lots of situations where you must beware unleashing the feedback-giving ethos:

–A new team member may not be the best person to give feedback. The new team member may not know what the right course of action is. However, that person is also a candidate to receive peer feedback, and hence will begin to experience the culture of giving and receiving peer feedback. But when first starting, perhaps you should not unleash the expectation to give peer feedback right away.

–Similarly, another team member may have trouble using behavior-based language. Don’t encourage this person to give peer feedback.

Tips for how a manager can improve direct peer feedback

Peer feedback can be a tricky thing. When it is given indirectly, such as via 360 feedback surveys, it potentially makes a mess that is hard to clean up. But what about when peer feedback is directly given? There are pros and cons for peer feedback directly given, and perhaps the biggest argument in favor of direct peer feedback is that it multiplies the amount of performance feedback an employee receives.

Use these tips to encourage your team to maximize the pros and minimize the cons:

1. Get the team, in addition to the manager, good at giving feedback

The Manager by Design blog knows how badly given feedback can ruin so many things about the work environment. And there is an epidemic of badly-given feedback out there, and for this reason I have some hesitation to recommend in this post that the lines of feedback be increased, since it could be increased badly given feedback.

However, performance feedback is such an important performance driver that this must be overcome! There are ways to improve how you give feedback and can identify what good feedback looks like. This blog provides a number of tips on how to improve the feedback, from making it specific and immediate to using behavior-based language, to seeking direct observation and feedback opportunities. There are many examples of great training opportunities to learn how to give performance feedback. In the Seattle area, I recommend Responsive Management Systems, which provides services that will improve how you prepare to give feedback and give feedback that gets the results you want. Of particular interest related to this topic is their “Responsive Colleague” program.1

An opportunity to increase the amount of performance feedback on your team

Peer feedback is frequently given via indirect surveys, perhaps as part of a 360-degree feedback program. I would like to argue that this doesn’t really count as peer feedback, since it is time-delayed, indirect, and frequently non-actionable. I’m more in favor of direct peer feedback, since it is specific and immediate, can be focused on improving performance and teamwork. However, there are some reasons to be wary direct peer feedback, as I detail in my previous post.

However, the main reason I’m in favor of direct peer feedback is that it multiplies the amount of performance feedback that team members receive. Let me explain:

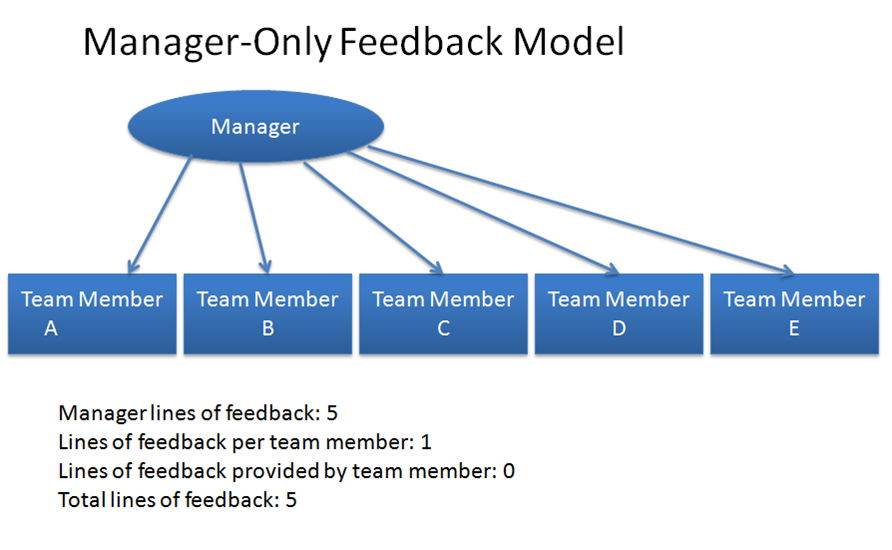

A traditional model for how employees improve their performance is through manager observation, and then the manager provides coaching and corrective feedback. For a team of five people, this is what it looks like:

Look familiar? This is the popular conception for how employees receive feedback on their performance. It is predicated on the belief that the manager has enough expertise in all the areas of the team performance to provide feedback, and the manager actually has the skill to provide feedback, which, alas, is not always the case. When most of us start a job, this is the general mental model that we have. After all, the manager is the one who evaluates our performance, and knows the expectations for performance! Employees expect to receive feedback from the manager on performance.

The Value of Providing Expectations: Positive reinforcement proliferates

In my previous article, I noted how setting team expectations can help a manager identify when and how to provide corrective feedback.

There is another value to providing expectations to your team: It allows you and your team to provide reinforcing feedback, and more of it. Reinforcing feedback, also known as positive feedback, is much easier to give and receive than corrective feedback. The key is to reinforce the right thing!

That’s where the expectation-setting comes in. If the team expectations have been set, then they can be reinforced. On the flip side, if no expectations have been set, then what gets reinforced will be generally random. Some of good behaviors get reinforced, and some of bad behaviors get reinforced.

So if you set team expectations, then you and your team are much more likely to reinforce the desired behaviors. As previously written on this blog, the manager should be spending a good chuck of time reinforcing positive behaviors.

In the example I used in the previous article, was the manager set the following general team expectation:

The team will foster an atmosphere of sharing ideas

In this example, let’s say the team actually conducts a meeting where the various team members support each others’ ideas, and allowed everyone to provide their input. The manager observes this and agrees that this reflects the expectation of “fostering an atmosphere of sharing ideas.”

Now the manager needs to reinforce this! The manager can reinforce this in a few different ways.

1. Feedback to the group at the end of the meeting

At the end of the meeting the manager can say:

“This meeting reflected what we are looking for in fostering an atmosphere of ideas. I saw people on the team asking others for their ideas, and I saw that ideas, once offered, weren’t shot down and instead were praised for being offered. This allowed more ideas to be shared. Thanks for doing this, and I like seeing this.”

The value of providing expectations: Performance feedback proliferates and becomes more artful

I’ve written several articles lately about providing expectations to your team on how to perform. These articles describe how to increase the artfulness of providing expectations or setting expectations for behavior. For example, the expectations should:

— be set earlier rather than later

— include standards of performance where documented

–provided general guardrails of behavior

— should attempt to tie into the larger strategy

I’ve also written articles about how providing performance feedback to your team as a key management skill. Now let’s take a look at an example of how providing expectations can help you in providing performance feedback.

1. Performance feedback you provide happens more naturally, immediately and specifically

If you have provided expectations for how the team works together, and the guardrails of behavior are established in some form, you now have a context and standard of performance to start any performance feedback discussion when you see the need for someone to change what they are doing. Let’s take a look at a performance feedback example:

The art of providing expectations: Tie the expectations to the larger strategy

Providing expectations for how the team operates is an important skill for any manager or leader. It doesn’t matter what level of manager you are, this is an important early step to establishing yourself as a manager and leader, and to set the right tone that reflects your values as a manager and your team’s values for how it executes its duties.

In previous posts, I’ve discussed the following artful elements of providing expectations:

Establishing expectations early

Using existing performance criteria for specific tasks

Providing general guidelines for behavior

Today I’ll discuss how to tie in the act of providing expectations with the larger strategy of the team and organization.

Providing expectations is different from defining the larger strategy of a team. The larger strategy of a team or group dictates more what the team is working on and the resources it devotes to working on it to create a result greater than the individual work items. The strategy should indicate what it is the team is actually producing. The expectations should be consistent with the strategy and be the next layer down that translates more closely to the behaviors you expect and the areas the team should be working on.

So the expectations should feed into the larger strategy of the team or group. If you don’t have a strategy, perhaps it’s time to get one! It’s kind of a big topic, but let’s try to tackle it!

Let’s take a look at some examples of expectations that feed into a team or org strategy:

The art of providing expectations: Describe the general guidelines of behavior

Providing expectations for how the team operates is an important skill for any manager or leader. It doesn’t matter what level of manager you are, this is an important early step to establishing yourself as a manager and leader, and to set the right tone that reflects your values as a manager and your team’s values for how it executes its duties.

In my previous post, I describe two aspects of providing expectations: Get team input and provide expectations early rather than reactively. In today’s post, I’ll discuss another aspect of providing expectations: Set guidelines – the more you can do this, the more artful the expectation providing.

In discussing the performance management part of being a manager, I advocate for specific and immediate feedback, using behavior-based language. That’s for providing feedback. Providing feedback comes after providing expectations.

When providing expectations, you are preemptively identifying the course you want the team to go on. However, you can’t anticipate all events, all behaviors, and all specifics. (If you can predict specifics, then check out this article on letting performance criteria be known.) Outside of the repeating tasks, in the expectation-providing arena, this is your chance to identify more broadly what the team should focus on and how it should provide its focus. These should be considered guidelines or even “guardrails”.

The art of providing expectations: Get input and the earlier the better

The Manager by Designsm blog seeks to provide great people management tips and awesome team management tips. An important skill that managers need to have is the act of providing expectations for how the team and individuals operate. In my previous article, I discussed how it is necessary for a manager to provide expectations for the repeatable, established tasks. But this does not describe all of the tasks that many teams are expected to perform.

Many times teams, in addition to the repeatable work, are doing something for the first time, and must go through iterations to get it right and get the work done. These are situations where the work does not have an established, repeatable rhythm, but is filled with problem-solving, new ideas and creative efforts. So in addition to the repeatable tasks, let’s talk about providing expectations for forging forward into unknown territory, which increasingly describes many work teams!

Because something is new, this does not mean that a manager does not need to set expectations. Instead, the manager must provide expectations on the level of how the team works together to achieve the goals set out for them.

So when I say “providing expectations,” I’m describing the act of establishing both the “what” the team on works on and “how” the team works together. It is the act of setting the baseline understanding of what the team does and how it does it. And once the repeating tasks are established and the criteria for quality are determined, these expectations can then be provided.

The art of providing expectations: If there are established performance criteria, then make them known!

The Manager by Design blog seeks to provide great people and team management tips. An important skill that managers need to have is the act of providing expectations for how the team and individuals operate. In a previous post, I provided examples of providing expectations to your team. It today’s post, I start a series of tips on how to better improve how managers provide expectations to their employees. I call it the art of providing expectations.

We’ll start with the basics: If there is a specific, established performance standard for something your staff must do, then make this known.

Here’s what I’m talking about. Let’s say that there are basic items that your staff must do and to a standard of quality that your staff must perform on an ongoing basis. You need to provide expectations for how these tasks are done and to what level of quality. Of course this is done all the time in many organizations, but there are many orgs that newly formed, fast growing, or simply disorganized enough where this has yet to be done. Let’s look at some examples of these:

In an IT department, it could be requirements gathering, and the document that is produced in the process.

In a strategy development group, the development process of the strategy (i.e., who needs to be discussed with and approval process), and the actual strategy document.

In a business development group, the core elements of a contract that must be performed and following the process for getting them processed.

Other basic expectations of behavior could be the following: When to show up for work (if this is important in your org), response time to inquiries from customers, when status updates are due, to whom, and in what format.

So many things. . . The common denominator for these “basic tasks” are that they are ongoing, repeatable, and proven that they can be performed by the average performer on your staff.

1. Identify what the basic things you expect anyone on your staff to do.

So think about the things on your staff that you expect them to do that are ongoing, repeatable, and proven to be able to be done. Now, is this documented anywhere? Or is there an implicit understanding that these things are performed? If you haven’t made this clear to your staff that these things are done on an ongoing basis, now is the time to start.