Putting out fires: Managers who “want it now” or “want it yesterday” are managing from a deficit

Have you ever had a manager who has a last minute request, “I need this now!” The more extreme version of this is, “I need this yesterday.” Usually, this is a new last-minute request, and this can be very disruptive and annoying to employees, and a sure sign that the manager is “managing from a deficit.”

Now, I’m not talking about jobs where there is a last-minute nature to the job. A firefighter’s job, is, by definition, a “last-minute” kind of job. The firefighter’s boss will no doubt say, “We need to do this right away!” But there is a lot of preparation that firefighters engage in – with the aid and coordination of their bosses — that goes into meeting the demands of that “last minute” request known as a fire.

I’m talking about a boss who interrupts your job to request something new, and it is needed soon. And this request is made with urgency, perhaps with some yelling involved. These are requests that are metaphoric fires, not actual fires.

So if you are someone on a team that seems to have a lot of “fires”, then read on.

Let’s take a look at some of the sources of these last minute requests (a.k.a., fires):

1. Is the request primarily to assure the manager looks better to his manager?

A common source of this kind of last minute request is to provide assistance to the manager in helping him report up to his manager what is going on, most likely the request of the manager above her. So, ironically, the request keeps rolling downhill. If you have an organization with more than three levels, you have at least three “sources” for needs for updates. If the upper management team does this consistently, such last-minute requests can start to appear to be the norm. For example, let’s say that the upper management decides to schedule an “all team meeting” and wants all of managers in the group need to present to the team. And it’s going to happen next week. Last minute request spawned!

So the team needs to stop what they are doing and instead create a report on what they are doing. When this happens, the manager is asking the team to take the “hit” and not the manager. The manager should have the option to say to his manager, “This would disrupt my team in achieving its goals, which have already been prioritized” and provide the level of reporting already agreed upon. The request can be made to add it to future reports, as part of the core team deliverables. The manager can choose to make an exception and start the “metaphorical” fire, but should also note this as an opportunity to renegotiate what reporting –and the timing of it– the upper management needs. Read more

Tenets of Management Design: The manager can do a lot to improve “flow”

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s 1990 book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience popularized the concept of “flow” and its importance. So let’s talk about a manager and “flow”. Managers can do a lot to improve flow, and good managementdesign,benefits from being highly focused on encouraging “flow” in the workplace. The more your employees have flow, the more likely they are to produce some pretty amazing stuff. So shouldn’t your management design be focused on improving the “flow” of the employees?

That means fewer disruptions, enabling longer stretches of greater focus. Here are some ideas for managers to improve flow:

The manager can start by not being a distraction. How many times have we had a manager who interrupts our work with both minor questions or new requests for work? With the advent of email, chat, texts, and any other communication mediums including actually stopping by, perhaps the worst offenders are managers who are in the habit of interruptingtheir employees. So good management design would encourage managers not to interrupt employees who are likely to be closer to “flow state.” If the employee seems to be in deep concentration, this is definitely the sign that the employee is not available to be interrupted. If the employee is not responding to emails, this is a sign that the employee is in a focused activity. The manager should have predictable times when they interact with their employees.

Why performance feedback is important – for managers and employees

The Manager by Designsm blog writes frequently about the importance of managers having the ability to give quality performance feedback. I’ve written about the need to use behavior-based language, and making sure the performance feedback is given in the appropriate timeliness and specificity.

But is giving feedback really necessary?

Yes.

Leslie Allan has a great article on the Business Performance blog that highlights the importance of quality manager feedback on employee engagement. She cites a Gallup survey conducted in 2009 that identifies how different “feedback styles” can have a huge impact in employee engagement.

The article highlights that a manager who does not provide any feedback will have almost no employee engagement. Then those who do provide feedback have much more employee engagement, with those managers who focus on strengths getting even more engagement — they’re 30 times more likely to manage engaged workers than no feedback. Read more

Without a strategy articulated, perhaps it’s time to start crowdsourcing one

In my previous article, I discuss how a necessary component of leadership is setting and articulating a strategy. If this is not done, then leaders become managers executing a strategy that has not been articulated, and, in essence, multiplying the number of managers executing a non-existent or randomly generated or constantly changing strategy. In other words, chaos.

In an earlier article, I discuss how one way to assure managers actually know the strategy is to ask them what they think the strategy and ask those reporting to the managers what they think the strategy is.

Now lets combine the two. Let’s go ahead and ask people in the organization what they think strategy is. Whether there is an articulated strategy or not, this process will, in essence, reveal what people in the organization think the strategy is.

Setting and articulating a strategy is not necessarily an easy thing to do, and even those in leadership positions seem to struggle with this. So “crowdsourcing” is at least a way to generate ideas and kick start the process of identifying and articulating a strategy. Read more

Do your leaders know and articulate the organization’s strategy? Read on for a deconstruction of leadership.

The last few articles I’ve published describe some tips for helping managers – strategy executors – to better understand and articulate an organization’s strategy. But perhaps I’m getting ahead of myself here – do the leaders even know the organization’s strategy and do they articulate it?

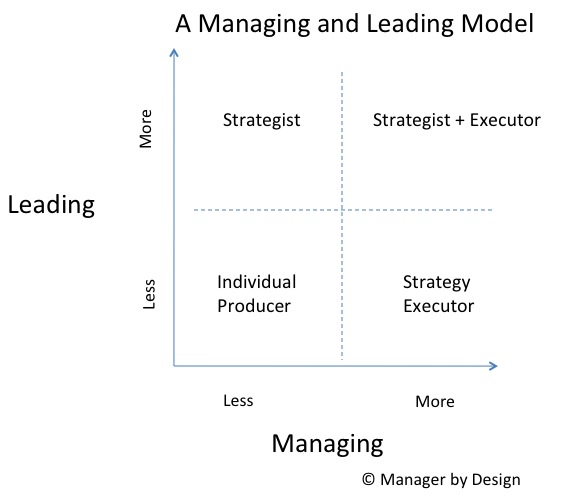

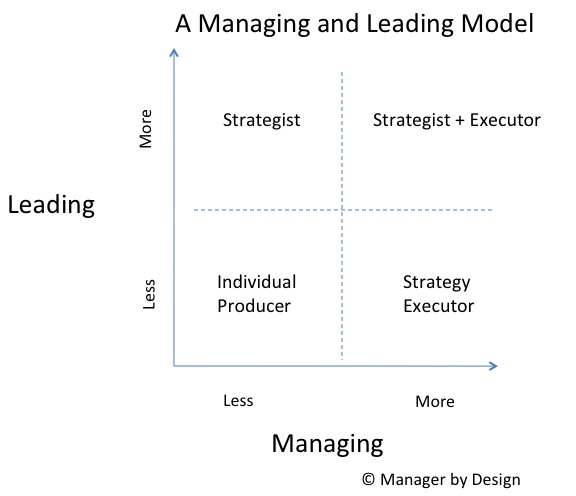

Let’s take a look at two grids developed by the Manager by Designsm blog.

In this first one, the Leadership/Management mode, those who are leading are basically the ones setting the strategy and then take steps to roll out that strategy. That’s what defines leadership here at the Manager by Designsm blog. But what happens if you don’t have leaders who do this? If that’s the case, they are doing something else. They are in a “leadership position” but are not leading. Read more

Management Design: How to include your managers in the strategy development process and develop leaders at the same time

If your organization has a strategy, it’s probably important that your managers – the strategy executors – be able to understand, articulate, and interpret the strategy well. If not, then this is bad management design. The Manager by Designsm blog’s leadership/management model makes the distinction of managers as strategy executors and leaders as strategy developers. So it is important that the managers be able to understand, articulate and interpret the strategy well.

One good design is to include managers in the strategy development process. It looks something like this:

But this should be designed to be done smartly and not in a haphazard way. An example of being sloppy in the design of “including the managers” is through having the management team regularly sit in on leadership meetings. This is a big waste of time, and would no doubt chart as low quality meetings.

Instead, the managers’ involvement needs to have the following elements:

a) Specifically selected managers (not all managers)

b) Be focused specifically on the strategy development process (not all leadership meetings)

c) The role needs to be defined with expectations to participate included (not just sit in)

d) It needs to be articulated that managers are assisting with the strategy development process (as opposed to, say, “You’re attending the ‘Leadership Meetings’”)

e) There needs to be an end to this process so the manager can go back to managing (not a standing invitation).

As a bonus, if the strategy development process is an involved one, the managers involved would be temporarily relieved of their duties as “strategy executor” manager, with the understanding that they will go back to this role.

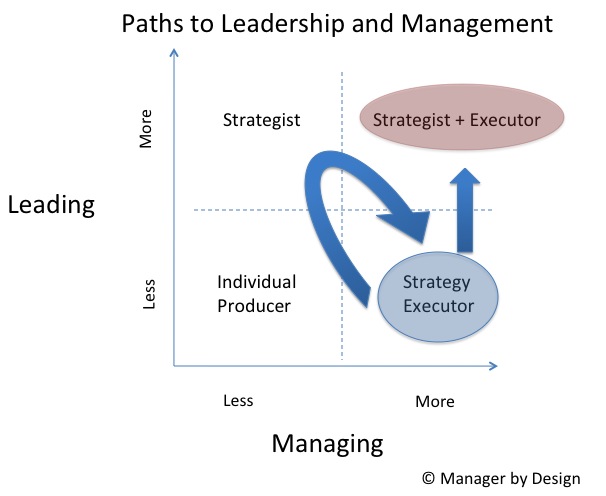

In this process, not only will the manager become better at managing, in that she (and her employees) will be able to articulate and interpret the strategy better, but she is also is aware of the strategy development process as a specific process, allowing her to become a better “leader” in addition to being a better manager.

Perhaps that manager will someday make a transition to being a “leader” and will be able to do – when in that leadership position — the following things:

- Articulate that there is a strategy development process

- Describe what that process is

- Replicate it and improve upon it when in the role of strategy developer

- Include the managers in the process

All of this while doing work that assists the current organization needs, and done on the job and not in a separate, abstracted training class. So the “leadership development” of the manager would look something like this:

The manager learns how to manage (strategy execution) and then learns how to lead (set strategy) and understand the difference between these actions, versus conflating these myriad of actions all as “leadership.”

As an extra bonus to including a manager in the strategy development process, the strategy itself will likely be better, as she can provide the needed perspective from the “strategy executors” on what they need to execute the strategy, and whether the strategy is going to work. As a double extra bonus, she will be to assist with the strategy implementation to other managers, assist with the ongoing interpretation to the other managers, all things that seem to assist with the current needs of the organization. In short, this is “leadership development” while doing the current job better.

The alternative I have seen is to have leadership development happen external to the job – -usually through a leadership development class or series of classes. These are effective at introducing the concepts, but do not allow for immediate applicability. This time delay will usually mean limited (if at all) application of the concepts. If you need classes at all, a better design would be to have the “strategy process” be taught to the manager (strategy executor) just prior to participating in the strategy development process.

Does your organization include the managers in the actual strategy development process? Or does it rely on developing its leadership through either classes or “sink or swim” methods?

Related Articles:

Management Design: The Designs we have now: The paths to management and leadership

Management Design: An alternative path to management and leadership: Loop in and out

Management Design: Structure and Feedback in a focused area of leadership

A model to show the difference between managing and leading

Do your managers know the strategy of your organization?

Tips for how your managers can better execute strategy

Tips for how your managers can better understand your strategy

How do managers learn strategy?

Management Design: A proposed design so that new managers embrace learning management skills

Tips for how your managers can better understand your strategy

The Manager by Designsm blog has recently been focusing on how managers – or “strategy executors” – can better align their work to . . . strategy executors. The Manager by Design blog believes that managers are strategy executors and leaders are the strategy developers. In my previous article, I provide tips for infusing the strategy into the manager’s goals/objectives, and testing whether the managers – and their employees — can articulate what the strategy they are supposedly executing is.

But managers need better performance support than simply putting the strategy in their goals. You want to make sure your managers are capable of making good interpretations of the strategy, and have some sort of specific and immediate feedback on these interpretations. Makes sense, huh? But how would you describe how your organization provides ongoing support for helping the manager interpret the organization’s strategy?

Here are some tips for improving this:

1. Provide access to those who developed the strategy

It’s one thing to have a group that develops the strategy, and it’s another to have that group accessible to help interpret the strategy. A strategy is, in essence, a summary statement of intent by leadership, so there are times when those who are carrying out the intent need to check in on whether their understanding of the intent is correct. To help with this, check the communications paths that are available to your managers. Do they have access to those who went through the strategy development process? Do they even know who developed the strategies? On the flip side, do people in the group who developed the strategy know who will be executing the strategy? If not, then there is a much lower likelihood that the strategy will be understood or interpreted by the strategy executors.

2. Include some managers in the strategy development process

First, I’m assuming that there is a strategy development process in the organization. If this is not the case, then perhaps it is time to consider one. If you do have such a process, how do you include the managers in the process? Many times the “inclusion” is the “announcement” of the strategy as a handoff to the managers, and that is it! But this, too, is a low percentage proposition in assuring your managers can understand, re-articulate and make good decisions based on the strategy.

One way to improve this “handoff” is to identify how managers are included in the process of strategy development when the process takes place. You don’t have to include all managers, and it doesn’t have to be the same managers each time the strategy development takes place. In doing this, no only do you assure that you have management inclusion, but when the strategy is “announced”, there are resources (see point 1) that are nearby that can better articulate the intent of the strategy and how it should be interpreted.

There are other benefits for including managers in the strategy process. In my next article, I’ll provide tips on how to include the managers (a.k.a., strategy executors) in the strategy development process and what some benefits of this process are.

Related articles:

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

A model to show the difference between managing and leading

Do your managers know the strategy of your organization?

Tips for how your managers can better understand your strategy

How do managers learn strategy?

Management Design: The designs we have now – Manager knows and supports only one possible strategy

Management Design: The Designs we have now: Part time strategist, part time manager

Current management design: The one with the ideas becomes the manager

Tips for how your managers can better execute strategy

The Manager by Designsm blog defines “management” as being the role of strategy execution, assuming your organization has a strategy. (See here for more on this topic of the management vs. leadership model). So one key to great management would be to assure managers are aware of the strategy, can articulate the strategy, make good interpretations of how the strategy translates to actions, and give feedback on how to improve the strategy.

How to make sure this happens? You want your managers to be good at strategy execution, and part of this is being able to understand and appreciate the strategy that is being executed. As part of the management design, you want to make sure that this understanding, articulation and evaluation of strategy execution is included into the manager expectations.

Have you ever had a manager who wasn’t able to really articulate why they were doing the things they were doing it? Instead, they are enforcing something? Or actively subverting the strategy? These are often bad managers. If they are bad at understanding the overriding strategy, their decision-making will be poor, their credibility with the workforce will be limited, and the results will not be aligned with the strategy.

Here are some management design ideas to help your organization have managers who are more aware of and more supportive of the strategy:

1. Create manager objectives aligned to the strategy

The first thing to try is to make sure the objectives of the strategy group (or wherever the strategy is coming from) — perhaps the strategy itself — are articulated in the manager’s objectives. Read more

Do your managers know the strategy of your organization?

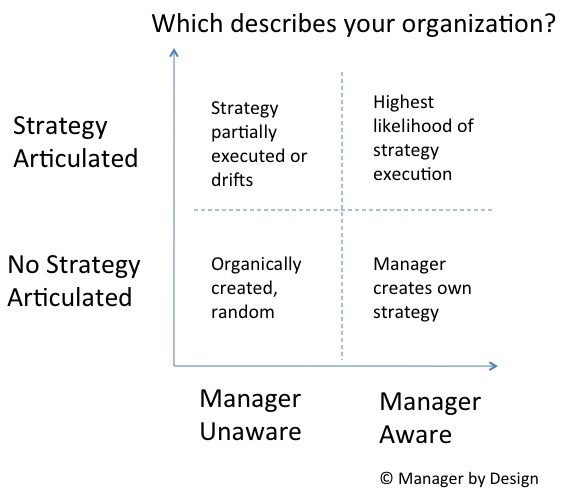

Most organizations, both at the highest level and the departmental level, are supposed to have a strategy. And the managers of these organization are expected to execute that strategy. Seems simple enough, but let’s test these assumptions.

Think about your organization. What is the overall strategy? Can you articulate it from memory? Can you look it up somewhere? What activities are you doing in your department that support the strategy? Do you know where the strategy comes from?

Now think about your department and the managers in it. Do they know the organization’s overall strategy? Can they articulate it from memory or look it up somewhere? Do they know where it comes from? And. . . do they have a strategy articulated for how they execute the larger strategy?

Let’s take a look at which quadrant your organization or department may be in:

In this view, I’ve placed four general possibilities in the grid. On the Y-axis, we have the scale of whether the overall organization has a clearly defined and articulated strategy. The lower on the axis, the less the strategy is articulated and the more it is assumed to be implied, or, perhaps, completely lacking. On the X-axis, you have manager awareness of the strategy. Sure it’s important to have a strategy, but how aware are your managers of it? The further you go to the right on the X-axis, the more the manager is able to articulate and interpret the strategy.

According to the Manager by Design management/leadership model, managers are generally in charge of strategy execution, so this would seem to be an important thing to examine! Read more

How do managers learn strategy?

The Manager by Designsm blog believes that there is a distinction between management and leadership. Management is tied to strategy execution, and leadership is tied to strategy development. Having a better understanding of this differentiation can help improve the “designs” in which organizations develop both managers (strategy executors) and leaders (strategists). Sloppy management design, in turn, is when you expect both management and leadership skills get developed all at once, or are delivered to your organization via recruited “talent.”

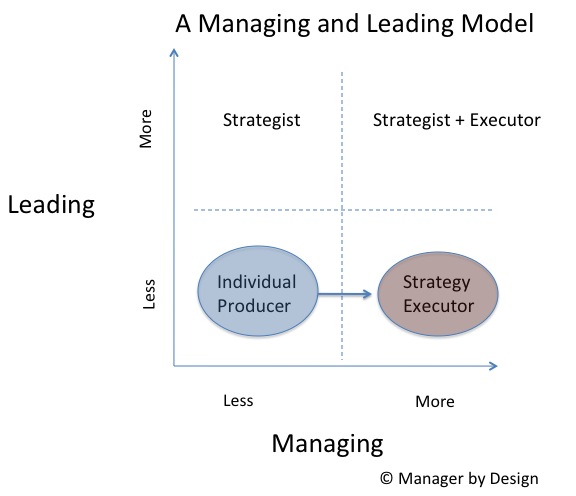

Here is the Manager by Design leadership and management model:

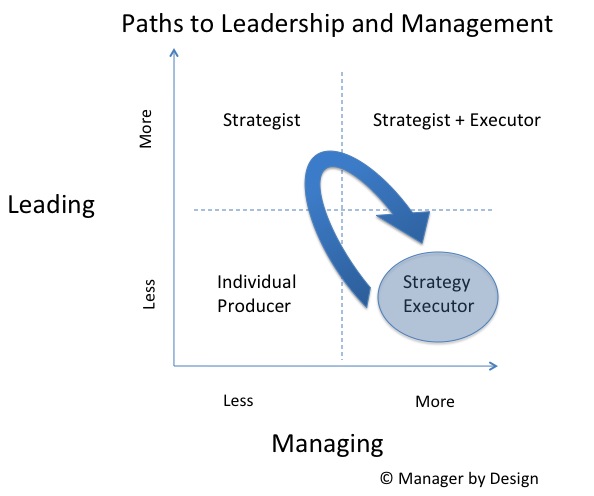

In the commonly held notion of “becoming a manager”, the path looks like this:

In this notion, the individual producer becomes in charge of the team doing the producing. The new manager is in charge of “strategy execution.” This is a fine model if there is some structure and feedback in performing the new managerial role, and a terrible model if there is no structure and feedback. It all depends on the management design of the organization. Are the managers designed to be great? Or are they left to their own devices in determining and creating their management practices?

Assuming that the manager has guidance in the core people management practices, there is another potential flaw with this scenario: The manager does not develop strategy skills or does not appreciate the act of developing strategy.

If your organization is looking to create leadership capability (in my model, the “develop strategy” quadrant), then there are a few paths that can be designed in to help with this potential design flaw while doing the job of managing.

1. Create objectives aligned to the strategy and clean handoffs between the strategists and the strategy executors

2. Assure and encourage access to the strategists and articulation of the strategy

3. Temporarily and cleanly have the manager participate in the strategy process

4. Provide the structure and feedback in developing the strategy for the strategy execution

Having elements like these in your management design will improve how managers who are in charge of strategy execution understand better the strategy, and, in turn, execute the strategy. The emerging field of Management Design must take this into consideration, and create designs that encourage the interaction and handoff between strategy and strategy execution.

It is the goal of the emerging field of Management Design to encourage managers to seamlessly execute the strategy of an organization. If it is being done poorly or haphazardly, then you will not get strategy execution, a main task of management. You may get some sort of execution, but will you get strategy execution?

In upcoming articles, I’ll discuss these potential designs for assuring that managers know the strategy, contribute to the strategy process, and develop their own strategy setting skills.

Related articles:

Management Design: The designs we have now – Manager knows and supports only one possible strategy

Management Design: The Designs we have now: Part time strategist, part time manager

Current management design: The one with the ideas becomes the manager

Management Design: The Designs we have now: The paths to management and leadership

Management Design: An alternative path to management and leadership: Loop in and out

Management Design: Structure and Feedback in a focused area of leadership

Management Design: A proposed design so that new managers embrace learning management skills

Tenets of Management Design: Focus on the basics, then move to style points