Using perceptions to manage: Three reasons why this messes things up

Today I start a series of articles on managers using perceptions to manage. A common way that managers attempt to do this is to use perceptions as a way of giving performance feedback and starting conversations with “There’s a perception that. . .” This is an indicator that the manager is attempting to manage perceptions. Here’s what I mean:

Have you ever had a manager give you feedback that starts with the words, “There’s a perception that. . .”? It may sound like this:

“There’s a perception that you aren’t delivering.”

“There’s a perception that you aren’t keeping up.”

“There’s a perception that you’re always late.”

“There’s a perception that you aren’t a team player.”

Managers who use the phrase, “There’s a perception that . . .” are attempting to manage perceptions. Here are the reasons that the phrase, “There’s a perception that. . .” need to be removed from a manager’s vocabulary and the effort to manage perceptions need to be refocused to other pursuits:

1. This may be feedback, but it isn’t Performance Feedback.

Managers attempt to manage perceptions via giving feedback on the perceptions. Using perceptions as the basis for feedback means that the feedback is on a phantom job external to the actual job. The performance of the employee — what the employee has actually done — has been removed from the feedback. The new implication is that the employee needs to manage perceptions in addition to doing the job. By giving this feedback, the manager has actually removed the duties of doing the actual job, and has inadvertently assigned new, and presumably more important duties to the employee: manage perceptions.

A second phantom job many employees have: Managing perceptions of others

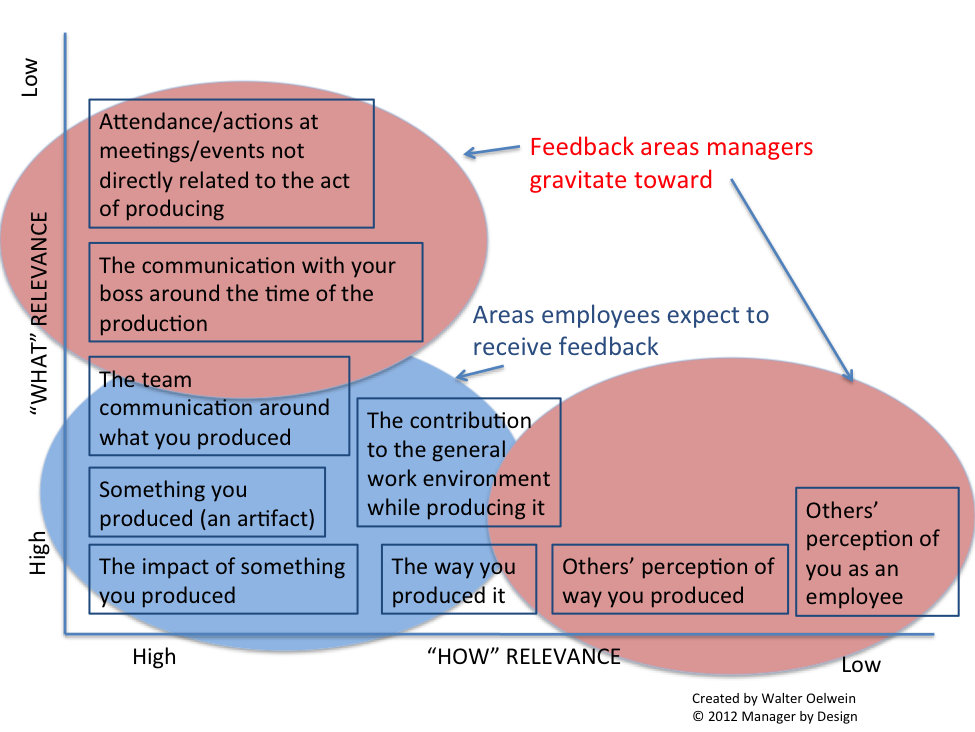

In my previous article, I shared a model to determine the relevance of the performance aspect of performance feedback that many managers give to employees. Here’s the model:

In looking at the upper left corner of this model, many managers create, via the act of giving performance feedback, a second job for the employee: How the employee performs in front of the boss.

So now the employee has two jobs: 1. The job and 2. The job of performing in front of your boss.

The model reveals also in the lower left corner that when a manager gives performance feedback, a third job is often created:

3. The job of managing the perception of others in how you perform your job. Read more

A model to determine if performance feedback is relevant to job performance

In my previous article, I discussed a common mistake managers make: They evaluate the “interactions with the boss” performance, and not the “doing your job performance.” So an employee can go through an entire year and not receive performance feedback on the work he was ostensibly hired to do, but receive lots of performance feedback on how he interacts with his boss.

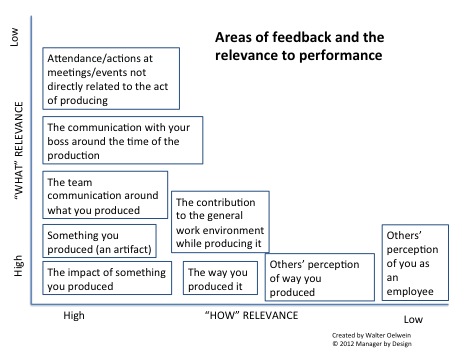

Given this concept of receiving feedback on the job performance vs. receiving feedback on the “in front of the boss” performance, let’s create a model to help managers get closer to the actual performance of an individual, and where the performance feedback needs to be.

Here is a grid that looks at various elements that employees commonly receive “performance feedback” on. I put these elements into boxes along the “what/how” grid, with the most relevant to job performance being toward the lower left, and the least relevant up and to the right.

In looking at this grid, you can see that what is most relevant is the impact of something produced, with the next most relevant elements being the actual thing you produced, and the way you produced it. Finally, the contribution to the general environment and the communication around the thing produced is the next most relevant element. The closer to the lower left, the closer it is it performance.

Performance feedback must be related to a performance

Have you ever received performance feedback about what you say and do in a 1:1 meeting?

Have you ever received performance feedback about your contributions to a team meeting?

Have you ever received performance feedback about not attending a team event or party?

Were you frustrated about this? I would be. Here’s why:

The performance feedback is about your interactions with your manager and not about what you are doing on the job. This is an all-too-common phenomenon.

If you are getting feedback about items external to your job expectations, but not external to your relationship with your boss, you aren’t receiving performance feedback. You’re receiving feedback on how you interact with your boss. The “performance” that is important is deferred/differed from your job performance, and into a new zone of performance – your “performance in front of your boss.”

OK, so now you have two jobs. 1. Your job and 2. Your “performance in front of your boss.”

A Performance Feedback/Performance Management Flowchart

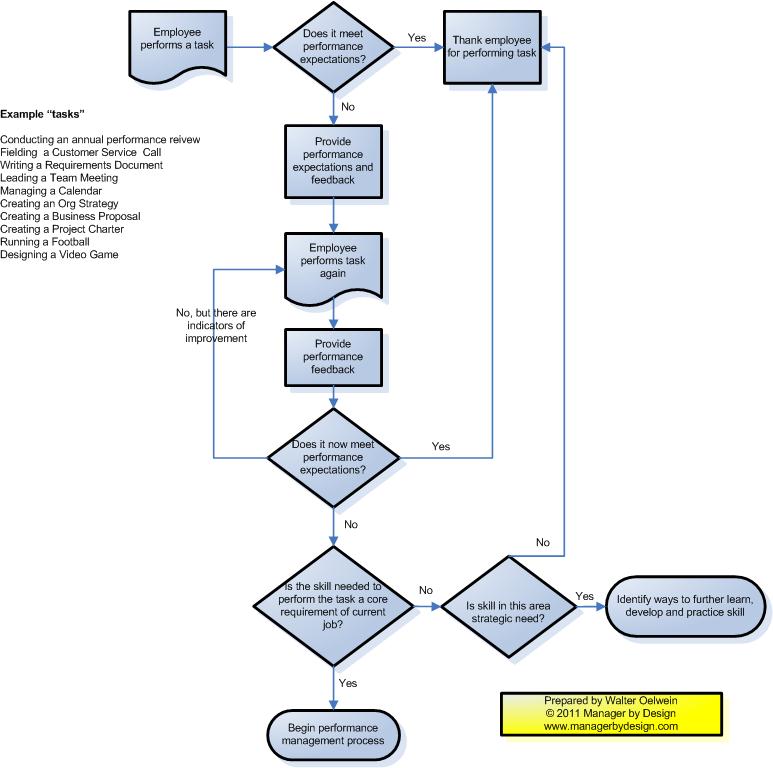

The Manager by Designsm blog seeks to create better managers by design. Here’s a great tool that outlines a simple flowchart of when a manager should provide performance feedback, and when the performance management process should occur. It can be used in many contexts, and provides a simple outline of what a manger’s role is in providing feedback, and how this fits with the performance management process (click for a larger image).

You’ll see that Performance Feedback starts at the task level, not the person level. You want to know what the task is, and make sure the individual gets feedback on how well he or she is performing the task. It also requires the manager to know what acceptable performance looks like. If not, then the manager is in a complex feedback situation, and both the manager and the employee agree to strategize on how to do the task differently, since it isn’t defined yet.

You’ll also notice that there is a lot of activity prior to the performance management process, which is actually a more formal version of this same flowchart. Managers need to perform this informal version first.

Let me know what you think. Do you your managers follow this flow chart? Do they skip steps? Do they add steps?

Related articles:

The Performance Management Process: Were You Aware of It?

Overview of the performance management process for managers

How to have a feedback conversation with an employee when the situation is complex

A tool to analyze the greater forces driving your employee’s performance

When an employee does something wrong, it’s not always about the person. It’s about the system, too.

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

What inputs should a manager provide performance feedback on?

When to provide performance feedback using direct observation: Practice sessions

When to provide performance feedback using direct observation: On the job

Five more markers and examples of what a good annual review looks like

In my previous article, I provided five markers of what a well-conducted annual review looks like. Let’s look at some more. It is possible to actually conduct an annual review well, but this is no guarantee. So let’s keep looking for those precious markers of a manager who knows how to use the annual review for good, rather than perpetuate it as a tool for suffering.

Marker #6: Improvement is germane to the discussion

If the annual review has any discussion about where the employee’s skills and performance was at the beginning of the year, and a comparative analysis at the end of the year – in those same skills – then this means that the manager is actually concerned with increasing the capability of the organization. I would consider this generally a good thing. For example:

“At the beginning of the year, we discussed how we can improve Alex’s presentation skills, as she frequently presents business partners. During the year Alex sought mentoring and feedback in this area, and the results show that this effort has paid off. Our partners have reported that they find her speaking style inviting and informative, and Alex has consistently been able to meet the objectives of the presentations.”

Marker #7: References to the goals

First, a marker would be that the employee and the team actually have some sort of goals. That would be the first marker of a good performance evaluation, as it provides something against which the manager evaluates the employee. Now, the second part of this is if the manager actually references the goals in making the evaluation.

“We had the ambitious goal at the beginning of the year to implement a new payroll system to further streamline what was before a highly labor-intensive project. Jeanine was a key part of the team that scoped the project, identified the goals of what success of the project was. Jeanine managed the vendor selection process, kept the team focused on the desired outcomes, and ensured that the team understood what was in scope and out of scope via her weekly communications. This was a key factor in assuring that the project stayed on track, which it did. The new payroll system was launched on time earlier this year, and has significantly reduced the processing time.”

Marker #8: Teamwork is referenced by both the employee and the manager

The individual performance review necessarily focuses on the individual. I consider this bad management design, as individual work is good, but teamwork can create greater outcomes. Almost all workgroups rely on teamwork. Managers and employees can transcend the design by invoking what teamwork happened during the review period. Let’s say that the manager talks about the great teamwork that the employee engaged in. Let’s say that the employee mentions how she contributed to building the team, and how she made an effort to improve the capability of the team, or looked out for the interest in the team. This would reflect that the manager and team are actually concerned with the power of teamwork over the expectation for an individual to perform independently of teamwork. Here’s an example:

“Jonathan demonstrated that he is an excellent team player by creating a process document that showed how to complete a task that many team members performed irregularly. This helped the team gain some efficiencies, and inspired other team members to make similar efforts. The team is healthier as a result of Jonathan’s efforts.”

Marker #9: Goals seem to have a similar voice and scope across team members

Many annual reviews have a section where the employee’s goals are documented. One could look at the goals of all the team members across a managers’ team. Imagine, if you will, goals that seem to have a similar tone, similar metrics, and similar scope across team members. They don’t have to be exactly the same, because not all roles are the same, but if the goals are all striving toward a similar metric or output, this demonstrates that the manager knows what the team is striving to do, and has actually infused it in the goals. When the goals seem to be similarly written, we also know that the manager has provided input and perhaps even co-authored the goals – or this is sometimes tough to imaging – this was done as a group. Too many times we see managers push down the goal writing process to the individual employees, which results in, by definition, different looking goals. Let’s celebrate those times when we see goals across the team show some kind of consistency across the team.

Marker #10: There is agreement between the employee and the manager

If a manager and employee seem to say that they agree about things on the performance review, this reveals that the employee and the manager actually talked about these things prior to the annual review. Differences in what the results were, what the impact of the employee’s actions and whether or not the employee performed at a high level – well these were resolved external to the review, as should be the case. Many managers wait until the review to resolve lingering disagreements, sometimes even using the review to create new ones, but those managers who seek alignment and understanding with their employees throughout the year, and don’t wait until the end of the year should be recognized as superior managers. Here’s what alignment looks like:

Employee: “I increased sales by 15% through my efforts to reach out to a new customer base.”

Manager: “I agree with the employee. He was effective at identifying a new target market, and then executing the strategy of accessing the market.”

See? no debate! Do you think that a debate might have happened during the year to get to this agreement of what the employee’s efforts were and what were the estimated results? Yes. Does it appear on the annual review? No, but the agreement of the results of the discussions do appear.

We should celebrate when managers do a great job on the perilous annual performance review, and do whatever we can to increase the chances of a well-conducted review.

Have you seen these markers of success on a review? Let’s hear your stories!

Related Articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

How to neutralize in advance the annual toxic performance review

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

I’ve recently published a series of articles that describe how annual reviews reveal more about the manager than the employee. The examples I’ve provided focus on examples of bad management practices that could cause damage and general resentment in the manager/employee relationship. But of course not all annual reviews are conducted poorly.

I know that for some of you out there this might be hard to believe. Just as it is easy to recognize poor management practices in action on an annual review, there’s the ability to identify when a review is done well. Here are some examples of markers of a well-conducted employee performance review:

Marker #1: Level of detail

A well-conducted annual review will show that both the manager and the employee have a mastery of the details of the role being reviewed. The details should include specific actions that the employee performed. The manager can demonstrate involvement in the actual work by discussing how she actually reviewed the work and found it at the desired performance level and what the impact of the work is, or is anticipated to be.

Marker #2: Agreement of metrics

First, let’s assume that there are success metrics (yes, numbers) that are documented somewhere on the review. That is a good sign. Second, let’s say that the manager and the employee BOTH refer to the same numbers on the review. That’s another good sign. So then we know that both the manager and the employee seem to be striving for the same numbers. That’s a third good sign. (We’re taking baby steps here. I would also be great if the metrics were tied to drivers of business/organization success – but let’s start really basic and have the employee and manager agree on a few metrics first.)

Marker #3: Referencing performance feedback/strategy sessions

When either the manager or the employee reference in the review actual feedback conversations (or what I also refer to as “employee strategy sessions”) that happened external to the review context, this is a good sign. That means that the manager has taken an active interest in the employee’s ability to perform the job well, and has taken the time to coach the employee. Also imagine the employee referencing in the review having been coached, taking the feedback and applying it, and then getting better results. That would be even a better sign.

Marker #4: The performance feedback/strategy sessions are related to the job functions and results

It’s one thing to have feedback discussions throughout the year, but it’s another to have feedback discussions that actually revolve around performing the job better. Many times managers stick to things that are closest to the manager, but are at best indirectly associated with doing the job:

“Jeff is late for our team meetings”

“Anne didn’t attend the all-team meeting”

“Isabelle needs to speak up during the team meetings”

“Mark brings up problems during 1:1 meetings”

OK, so those seem to be things revealing a lot about the employee/manager logistics, but nothing about the job. How about instead:

“Jeff created a strategic business plan that researched the competitive landscape. We identified some new tools he can use to create deeper understanding of our competitors, and he introduced to them to the organization.”

“When we found errors coming from our vendor, Anne identified the top issues and worked with the vendor to reduce errors and costs.”

“In looking at the contracts Isabelle writes, they are consistent, keep the company’s interests at the forefront, and delivered on time.”

“Mark is skilled at finding issues in the organization, and raising them such that they help the team run. One example is our outreach efforts to our partner teams. He identified that this was an issue, and he proposed that he and I meet with them to better understand how we work together. The result was that the partner teams have included us in key decisions that we wouldn’t have been involved with otherwise.”

Marker #5: An outside party can actually identify what the job is by reading the review

If you look at the above examples, you can actually start to guess what the employee actually does. This should be the focus of a review – most of the commentary should be on what the employee did, and how well, and whether they met the goals or improved things.

These are some (not all) of the markers of a well-conducted annual review. If you have managers that display these markers, perhaps you should praise them for doing this well?

Have you seen these markers on an annual review? Or is it more common to see the markers of poorly conducted reviews?

Related Articles:

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

How to neutralize in advance the annual toxic performance review

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

Performance Feedback is about next time

Here’s a scenario: Jim reacts badly to a new change in the organization. He starts telling all of his co-workers how much he doesn’t like the change, and discusses ways to undermine or avoid the change. This causes increased doubt in the change, and even causes confusion as to whether the change is actually going to happen.

Jim manager has the option of either addressing or ignoring Jim’s reaction. If the manager addresses it, this would be a performance feedback conversation.

However, many managers avoid the performance feedback conversation. One reason for this is the manager may believe that Jim’s behavior on the job is deeply embedded in the employee’s personality, and the employee’s actions are innate to their very being. So a basic thesis emerges that “Jim is just like that.” There is the belief that Jim just won’t change. So no performance feedback conversation is necessary.

But this is an untested thesis. Jim did react badly to the news, but does this mean that he has to react the same way next time? The answer is—you don’t know until you have the performance feedback conversation.

If you don’t have the performance feedback conversation, the Jim will definitely behave in the exact same way should a similar set of circumstances occur. His behavior was “negatively reinforced,” meaning that he received no information that his behavior was incorrect and he received no adverse reaction from his manager. In fact, his behavior may have also been “positively reinforced” when the other employees start agreeing with his arguments about how he doesn’t like the change. The manager, by being silent, is letting the other forces of behavior determine Jim’s behavior in the workplace.

So the basic thesis that Jim “always is like that” only is true if he never receives coaching or feedback on what he should do instead. And when the manager does not step in, then for sure this thesis will be proven correct.