Management Design: A proposed design so that new managers embrace learning management skills

In my previous article, I discussed how an improved design would be to have structure and feedback provided to those who take on a leadership/strategy role, however temporary. This way, they learn strategy while doing strategy. Seems simple enough, but how often is it done?

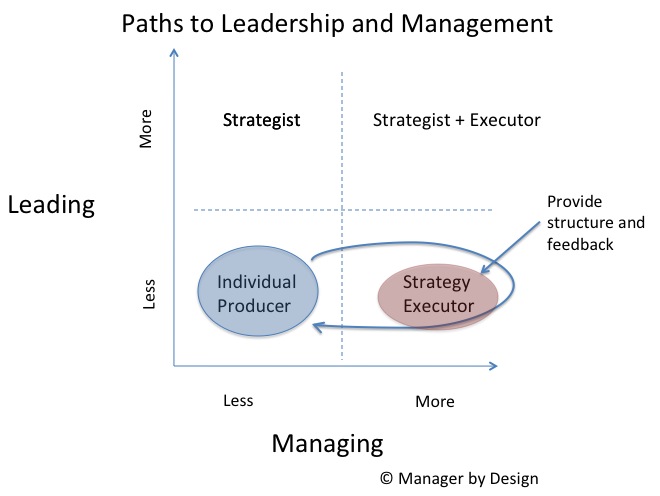

Now let’s transition the discussion away from leaders and to managers. In the Manager by Designsm leadership and management model, we can see how managers can learn their role using structure and feedback, and that it is possible to loop into the role and back out of it:

If someone goes into a team management role, they reason they have done this is to assure some sort of strategy execution. Sounds pretty important! So this sounds like a design requirement – makes sure someone is good at strategy execution.

The annual review reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance (part 3)

In my previous articles here and here, I discussed how the annual review process reveals more about the manager than the employee. The annual review’s text may be about the employee’s performance, but what really is powerful is the subtext – the manager’s practices as a manager.

Here are even more examples of what kinds of things are revealed about a manager in an employee performance review:

1. The Fight

Two articles ago, I cited “the debate”, which I characterized as a disagreement on the review over what happened over the course of the year. But sometimes you’ll see actual arguments spill over onto the review. The argument may be over points of fact, or points of interpretation, but if the two parties are extending their argument into written form when the annual review is written, then you know, at the minimum, that the manager is comfortable not resolving disputes, and letting them extend into a variety of forums and formats, and it probably doesn’t stop at the review.

2. Egocentrism

Many managers will talk about their own actions and contributions on an employee’s review. It’s one thing to talk about the team accomplishments, but when you see a manager say, “I was able to help Jim achieve an increase in sales,” or “I made a great hire in Tammy,” you can infer that the manager has more focus on him or himself than the team. Just count the number of “I’s” in the manager comments and you can get a feel for this.

3. The one good thing one bad thing

I have commented on this in a prior article – but this is a good time to revisit it. Many managers believe that they need to be “fair” in providing one good piece of feedback and one bad piece of feedback on an employee. “Jim was able to deliver a high volume of work, but sometimes his emails can be too long.” Doing this makes little sense, because typically employees do go to work and then do one thing good and one thing bad. If there is something that the employee needs to get better at to do her job, then this needs to be articulated as something the manager and the employee are already working on. It reveals a lot about a manager who waits until the review to articulate the wrong things the employee does without having any reference to an effort to improve the employee in that area. Perhaps this frequently happens because the “bad thing” that is cited is often irrelevant to the employee’s performance, “Max didn’t go to the team event.”

4. Areas irrelevant to the performance

The annual performance review is often a treasure trove of irrelevant feedback. Many managers will cite events that are not relevant to meeting goals (what time the person comes in every morning, the length of emails, for example). Look closely at what the manager critiques and praises. Is there a connection to the team achieving the metrics, or is simply something that is generally considered bad (being late on occasion, being slow to respond on email) or good (setting up a weekly happy hour), but not necessarily directly connected to work output.

5. The blank career development area

There are lots of places on the form to fill out. Sometimes managers do not fill in certain areas. A common area that often goes untouched is the career development plan. Many review forms have a “looking forward” section that discusses what the employee plans to do to develop his or her career. If this section is blank – and it often is – then you know for sure that the manager isn’t engaging in this discussion with the employee. If the manager does have it filled in, and it looks robust and connected to the employee, then you know that this is something the manager is good at.

But wait, there’s more! Tune in next week for more ways the review reveals more about the manager than the employee. What stories do you have?

Related articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

The Cost of Low Quality Management

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

Tenets of Management Design: Managing is a functional skill

The annual review reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance (part 2)

In my previous article, I discussed how the annual review process reveals more about the manager than the employee. The annual review’s text may be about the employee’s performance, but what really is powerful is the subtext – the manager’s practices as a manager.

Here are some more examples of what kinds of things are revealed about a manager in an employee performance review:

1. The lack of detail

The manager usually has a comment box in an employee review form. If the manager does not write much in it, what does that tell you? Probably that the manager has no idea what the employee did over the course of the year. Compare the following:

“Joe had a great year. He met all of this goals and is well-liked on the team.”

“Tiffany created a new system that was implemented across the team to improve communication, streamline processes, and create more accountability. She identified the largest issues facing quality teamwork, and her efforts in this area contributed to a better team understanding of the deliverables and timelines.”

In the second example, the manager appears to know what Tiffany did. In the first example, it is not clear whether the manager even knows who Joe is, and what he does.

2. The lack of discussion of improvement

One of the tasks of a manager is to facilitate an ever improving team atmosphere and capability. Or, at the minimum, get it to an acceptable level and keep it there. But what if you never see any language that expresses any effort to improve the team or its members?

Something like, “At the beginning of the year, Andy and I discussed improving his follow-through on resolving quality issues in his work. We worked together to identify how we can improve in this area, and during the year, Andy had many fewer issues in this area. In fact, Andy is now a team champion on how to assure our team’s work output is both timely and with quality.” This indicates a drive for improvement.

Instead we often see the flat, “Andy has quality issues.” In this case, we quickly learn that the manager sees no responsibility in improving Andy’s quality issues. This indicates a quality issue of the manager.

3. The disconnect from goals

Many performance reviews have a section that require employees and managers to compare the actual results of the work with the goals established at the beginning of the review period. It is often observed that managers will not comment on these goals and whether or not they were met by the employee, and instead focus on personality elements. Perhaps you’ve seen something like: “Joan brings a lot of fun to the team!” “We love Harry’s sense of humor and positive attitude.” That’s on the positive side. On the negative side, it might be, “Marty is always late for meetings” or “Patrick could improve his attitude” or “Maurice could be more helpful with other team members.”

If the manager writes something that is not connected to the goals and does not reveal her opinion as to whether or not the employee met the goals, we learn that the manager didn’t take the goals seriously in the first place, or doesn’t know whether they were met.

4. Comparison of goals across team members

Sticking to the topic of goals, one exercise is to compare the goals across the manager’s team members, which are usually documented on the annual review. Are they the same? Do they appear to lead to a team strategy? Or do they appear written independently by the individual members of the team? One team member may have tons of goals, and another may have hardly any. Are one set of goals very crisp and another set of goals unformed and vague? That can happen if the manager is not taking the goal-writing process seriously, and has not provided input.

5. Expectation of teamwork

The manager is ostensibly a leader of a team, not a series of individuals. However, the annual review typically has very little commentary about how team members helped one another. If the manager does not have discussions somewhere in the review (goals, what the team achieved vs. what the individual achieved) that identify the quality of teamwork, then we know that this is not a priority of the manager. Is this the kind of management practices we are looking for?

My next article will discuss even more examples of when a manager reveals more about herself on the employee’s performance review.

Do you have examples of when the review says more about the manager than the employee? Send them my way!

Related Articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

The Cost of Low Quality Management

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

The annual review reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance (part 1)

I have written in the past about “the annual toxic performance review.” The basic point is that this is the only time many managers provide insights – the view – on how the employee is performing, is during the re-view. The view in to the employee’s performance is often during the re-view. Kind of ironic.

Another ironic situation is that the employee’s annual review usually reveals more about the manager’s performance than the employee’s performance. Yes, the review covers all sorts of aspects of the employee’s performance, usually both from the employee’s perspective and the manager’s perspective. That’s the text.

But the subtext of any employee performance review is how well that manager managed the employee during the review period. And looking at a manager’s reviews from this perspective will quickly reveal lots about how that manager manages.

Let’s take a look at some examples of how the review reveals information about the manager:

1. The debate

Many times you will see a debate emerge about the employee’s performance via the employee’s self evaluation and the manager’s comments. If there is disagreement, this reveals that the manager has not discussed the employee’s performance openly with the employee during the year, and has instead waited until the performance review to share his thoughts. The employee, perhaps anticipating this debate, will submit multiple pieces of evidence (metrics, stories, customer quotes) to pre-empt the anticipated contrarian position of the manager. It’s interesting to see if the manager’s comments actually address these pieces of evidence, or ignore them and make generalizations about the employee’s performance.

2. Performance Feedback on the review

Many times you will see a manager finally take that step and provide feedback to an employee via the review. “Jim needs to be more accountable.” “Alex needs to manage meetings better.” “Alyssa has quality issues that have hurt the team.” “Patrick needs to connect with his peers more.” (Note: As these are generalizations, they are poor examples of performance feedback, but nonetheless examples of performance feedback likely to be found on the review.) If the manager gives this feedback and does not reference a conversation to this effect in the review (i.e., “We discussed how Patrick can engage with his peers”), then the manager has simply waited until after the review period to give performance feedback. As discussed many times in this blog, this is the most un-artful way to manage and to provide performance feedback, as it is neither specific nor immediate.

Yet so many managers do it today, it has become almost a norm. Should you see this on your organizations’ annual performance reviews, expect there to be contempt for the managers in your org.

3.The “keep it short” instruction and subsequent debate

Many annual review forms have an employee self-evaluation section, and then a manager comment section. Managers often give instructions to their employees to “keep it short.” That is – don’t write much about your performance. This reveals much about the manager – a) The manager does not want to hear about good work being done by the employee, and wants to deny that opportunity of expression b) The manager is trying to limit discussion of and knowledge of what the employee accomplished c) Apparently doesn’t want to read more than a page of text and; d) Wants to give negative feedback during the review (see point 2 above), but fears that the employee may submit evidence that this negative feedback is incorrect, so the best mitigation strategy by the manager is to cut off discussion. Often there will be more debate – in the review form itself, prior to the discussion, and during the discussion – about the amount of text an employee can enter in the review form than there is a discussion about the employees performance. Crazy.

What are examples you have of managers revealing more about their performance on the annual review? Send them to me!

In my next article, I’ll provide more examples of how the annual review reveals more about the manager than the employee.

Related articles:

Let’s look at what a well-conducted annual review looks like

The Art of Providing Feedback: Make it Specific and Immediate

An example of giving specific and immediate feedback and a frightening look into the alternatives

Why the annual performance review is often toxic

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

How to improve management design: Look at examples of high-profile careers that receive a lot of performance feedback

The Manager by Designsm blog discusses performance feedback a lot. That’s because it is an art that is practiced either in a limited manner, or poorly. At the same time, performance feedback is a significant driver to improved performance of people on your team, perhaps the most significant driver. If you imagine the alternative – no performance feedback – you will have a situation where whatever level of performance you are at will either stay the same or get worse. Similarly, the professions that seem to be the most visible and most public seem to get the most performance feedback. Some of it is requested, and some of it is unsolicited, but in all cases, if the profession is important enough, the performance feedback comes in frequently, specifically, and immediately.

Let’s take a look at some example professions that receive performance feedback, and how that feedback is delivered:

Professional athletes: Professional athletes get feedback in the following ways:

–Coaching during practice and games

–Sportswriters during practice and after games

–The public during games and after games

–The scoreboard

–Statistics

–Analysis of statistics

–Comparisons to other athletes’ statistics

–Playing time

Examples of how peer feedback from surveys is misused by managers

In my previous post, I describe how peer feedback from 360 degree surveys is not really feedback at all. At best, it can be considered, “general input from peers about an employee.” Alas, it is called peer feedback, and as such, it risks being misused by managers. Let’s talk about these misuses:

As a proxy for direct observations: Peer feedback is so seductive because it sounds like something that can replace what a manager is supposed to be doing as a manager. One job of the manager is to provide feedback on job performance and coach the employee to better performance. However, with peer feedback from surveys, you get this proxy for that job expectation: The peers do it via peer feedback. Even better, it is usually performed by the Human Resources department, which sends out the survey, compiles it, and gives it to the manager. Now all the manager has to do is provide that feedback to the employee. See, the manager has given feedback to the employee on job performance. Done!

Never mind that this feedback doesn’t qualify as performance feedback, may-or-may not be job related, or may-or-may not be accurate.

The incident that sticks and replicates: Let’s say in August an employee, Jacqueline, was out on vacation for three weeks. During that time, a request from the team Admin came out to provide the asset number of the computer, but Jacqueline didn’t reply to this. And worse, Jacqueline didn’t reply to it after returning from vacation, figuring that the admin would have followed up on the gaps that remained on the asset list. Then it comes back a year later on Jacqueline’s peer feedback that the she is unresponsive, difficult to get a hold of and doesn’t follow procedures. This came from the trusted Admin source!

Why peer feedback from surveys doesn’t qualify as feedback

In a previous post, I identified peer feedback from 360 degree surveys as a source of inputs where a manager gets information about an employee’s performance. Peer feedback via 360 degree surveys has become increasingly popular as a way of identifying the better performers from the lesser performers. After all, teams should identify people who get great peer feedback, and do something about the team members who get poor peer feedback. The better the peer feedback, the better the employee, right? Well, maybe. Maybe not. Let’s talk about how peer feedback should be used, and not misused.

OK, peer feedback. As Demetri Martin would say, “This is a very important subject.”

First of all, by definition, peer feedback on surveys is, from the manager’s perspective, indirect reporting of an employee’s performance. The peer gives the feedback via some intermediary source (survey, email request, or, if requested, verbal discussion), and then that information gets interpreted as to what it means by the manager, or perhaps even some third party algorithm.

So it is essentially hearsay. Since it is one degree away from direct observation of performance, peer feedback is inherently more risky to use as a way to provide feedback on an employee’s performance. Here’s why:

The best feedback – or the most artful, as I like to say – has the following qualities, amongst others:

–It is specific

–It is immediate

–It is behavior-based

–It provides an alternative behavior

Let’s see how peer feedback stands up!

Specificity: Peer feedback on surveys comes in the form of a summary of behaviors over an aggregate period of time. Sample peer feedback will say something like, “John is always on top of everything, which I enjoy,” or “John needs to stop checking messages during the team meeting.” Now here’s the rub: This looks like general feedback, but it may be (you don’t know for sure) related to one incident. The “on top of everything” may refer to arranging a co-worker’s birthday party. The “check messages during a meeting” may have happened during the one meeting when his daughter was undergoing surgery. Or it could be something that John always does. You don’t know. It’s general or it’s specific. You don’t know.

Or. . .have you ever seen this kind of peer feedback?

“During the September 18 team meeting, John was checking his messages when he should have been working with the team to brainstorm solutions to resolving the budget shortfall. Then, on the September 25 team meeting, John received two phone calls during the meeting, interrupting the discussion flow about what our strategy for next year should be. Then, on October 2, John. . .”

This kind of peer feedback doesn’t happen on surveys. Instead, you get summaries of behaviors that may be based on a specific incident. . . or not. It may be work-related, or not. You don’t really know.

What to do when your boss gives feedback on your employee? That’s a tough one, so let’s try to unwind this mess.

Here’s the scenario:

Your employee meets with your boss for a “skip level” meeting. After the meeting, the employee’s boss’s boss (your boss) tells you what a sharp employee you have.

Or, let’s say that your boss tells you that your employee needs to “change his attitude” and “has concerns about your employee.” This is very direct feedback about the employee, and it comes from an excellent authority (your boss), and if you disagree with it, you disagree with your boss.

But this information is entirely suspect. Whether the feedback from the “big boss” is positive or negative, the only thing it reveals is how the employee performed during the meeting with the boss. And unless your employee’s job duty is to meet with your boss, it actually has nothing to do with the expected performance on the job. So if the feedback is negative, do you spend time trying to correct your employee’s behavior during the time the employee meets with the big boss, when it isn’t related to the employee’s job duties?

In addition, the big boss often prides him or herself on the ability to cut through things and come to conclusions quickly, succinctly, and immediately. The big boss will come to a conclusion about the employee based on the data provided in the one-on-one meeting, and will expect this conclusion to be corroborated by you and everyone else.

The big boss, in this process, will put a tag on the employee, whatever it is. Here are some examples of tags:

Up-and-comer

Introverted

Not a go-getter

Whip-smart

Not aware of the issues

Could be a problem

. . .or, the dreaded, ambiguous, “I’m not sure about him.”

What’s worse, since the “tag” originated with the big boss, it will likely stick.

Tips for how managers should use indirect sources of information about employees

In my previous articles, I’ve provided warnings about using indirect sources of information about your employees to provide performance feedback. The reasons are numerous, some of which are provided here and here. Indirect sources of information about your employees performance may include “feedback” from sources such as customers, peers or your boss. We may call this “feedback”, but it isn’t really feedback, since it is, by definition, time delayed and usually non-specific. This makes it, for the most part, non-actionable. So this information – while copious — doesn’t merit the high bar that is “feedback.” However, this is information about your employee, so let’s look at some ways to maximize the value of this information – instead of just passing it along as non-specific and non-immediate “feedback.”

What to do with indirect information about your employee

a) Try to get more info

If you get some sort of “feedback” about your employee, at least try to get information about what it is that the employee did to earn the feedback.

Let’s say your boss tells you that your employee, John, “Nailed it this week.”

Bonus! Six more reasons why giving performance feedback based on indirect information is risky

I’m a big advocate for managers to give performance feedback to their employees. But the performance feedback has to be of good quality. So let’s remove the sources of bad quality performance feedback. One of these is what I call “indirect sources” of information. These include customer feedback, feedback from your boss about your employee, the employee’s feedback. These are all sources of information about your employee – and provide useful information, but they are not sources of performance feedback.

In previous articles, further outlined what counts as direct source of information about an employee’s performance (here, here, and here). And in my prior article, I describe how indirect sources are, by definition, vague, time-delayed, and colored by value judgments, making them feedback sources that inherently produce bad performance feedback when delivered to the employee.

There are more reasons a manager should hesitate using indirect sources of info as “feedback.” Let’s go through them.

1. Have to spend a lot of time getting the facts straight

Let’s say your boss tells you that one of your employees, Carl, did a “bad job during a meeting.” The natural tendency is to give feedback to Carl about his performance, using the boss’s input. When sharing feedback from this indirect source, you will need to go through a prolonged phase of getting the facts straight. First you have to figure out the context (what was the meeting about?), then you have to figure out what the employee did, usually relying on some combination of what the feedback provider (not you) observed, which, is typically not given well, and what the employee says he did. This usually takes a long time, and by the time you’ve done this, you still aren’t sure as to what the actual behaviors were, but an approximation of the behaviors from several sources. So the confidence in feedback of what to do differently will be muted and less sure.