Examples of how peer feedback from surveys is misused by managers

In my previous post, I describe how peer feedback from 360 degree surveys is not really feedback at all. At best, it can be considered, “general input from peers about an employee.” Alas, it is called peer feedback, and as such, it risks being misused by managers. Let’s talk about these misuses:

As a proxy for direct observations: Peer feedback is so seductive because it sounds like something that can replace what a manager is supposed to be doing as a manager. One job of the manager is to provide feedback on job performance and coach the employee to better performance. However, with peer feedback from surveys, you get this proxy for that job expectation: The peers do it via peer feedback. Even better, it is usually performed by the Human Resources department, which sends out the survey, compiles it, and gives it to the manager. Now all the manager has to do is provide that feedback to the employee. See, the manager has given feedback to the employee on job performance. Done!

Never mind that this feedback doesn’t qualify as performance feedback, may-or-may not be job related, or may-or-may not be accurate.

The incident that sticks and replicates: Let’s say in August an employee, Jacqueline, was out on vacation for three weeks. During that time, a request from the team Admin came out to provide the asset number of the computer, but Jacqueline didn’t reply to this. And worse, Jacqueline didn’t reply to it after returning from vacation, figuring that the admin would have followed up on the gaps that remained on the asset list. Then it comes back a year later on Jacqueline’s peer feedback that the she is unresponsive, difficult to get a hold of and doesn’t follow procedures. This came from the trusted Admin source!

More reasons the big boss’s feedback on an employee is useless

Perhaps I’m obsessing about this scenario too much, but I just can’t get out of my head the damage that managers of managers cause when they start assessing employees not directly reporting to them. I call this “tagging” an employee.

In a previous post, I describe the moment where a “big boss” (the employee’s manager’s manager) meets with an employee (or even just hears something about an employee or sees a snapshot of the employee’s work) and provides an assessment of the employee. “That employee really knows what she’s doing!” “That employee doesn’t seem to have his head in it.”

The problem? There are many:

–It rates the employee on behaviors not directly related to doing the job, but it’s based on an abstracted conversation about the work or a limited impression of the employee.

–It puts the manager in the middle in a situation where it would seem appropriate to correct the employee, even when it is inappropriate.

I describe what the manager ought to do about this here. But I’m still obsessed with the peculiar angst that this kind of indirect feedback will create in the employee – even when the “feedback” is good. So before I dive into my obsession, my advice to the managers of managers out there: Don’t provide assessments on an employee. Keep it to yourself. If you are really into assessing an employee’s value, you have to do the work of direct observation of work performance.

Now, let’s look at this “feedback” from the employee’s perspective and the damage it causes in an organization:

When a big boss starts trying to identify the top performers and the bottom performers based on their limited interactions, here is a survey of the damage it causes:

Makes employees one-dimensional: The employee immediately transforms from a multi-talented, hard-working, problem-solving contributor to whatever the “tag” is. This is bad even if the tag is good! If the tag is “hard working”, it diminishes the problem-solving, multi-talented part. It also creates a cloud around what the employee does the whole time at work, and instead puts a simplistic view of the employee’s value.

Assumes that the employee is like that all the time: Similarly, if the employee does a particular thing that gets the big boss’s notice, then that is the thing that the employee has to live up to or live down. For example, if the employee does a great presentation, that is what the employee is seen as being good at – the presentation, and the employee is expected to be presenting all the time to have value. There’s no visibility into the teamwork, project management, collaboration, technical insights, or creativity that went into the presentation. Just the presentation. Then if the person is not presenting all the time, then perhaps they are slacking off? That’s what the big boss might think!

On the inherent absurdity of stack ranking and the angst it produces in employees

Today I want to talk about a management team and how it relates to employees. Imagine the management team. They are in charge of the project of evaluating the performance of their collective employees. In some organizations, they are asked to “stack rank” all employees in an organization, or at least put them in general categories, such as low performer, average performer, high performer, or some variation like, “Needs improvement” at the bottom of the rank to “High Potential” at the top of the rank.

OK, now the management team needs to do the work of ranking the employees. The person facilitating this process is likely to be the manager of the team of managers, or the manager above that. So you have a bunch of managers in a room discussing a large batch of employees’ performance, making arguments about who is a good performer, who is an average performer and who is a low performer. Oftentimes there is a forced curve that requires some people into the “needs improvement” bucket. Oftentimes these discussions have promotion implications and bonus implications. In the examples of companies that have adopted the “fire the lowest 10%” philosophy, it also has firing implications.

Inevitably, the employees know that this kind of thing is happening between the managers. This is a common practice at many large organizations, and a tough one to get right. I’m not really sure it is possible to get right, and here’s why.

In a discussion like this, each manager is armed with some data about the employee. As discussed frequently in this blog, that data about how an employee performed is limited at best, and non-existent at worst.

There are cases where there are specific metrics that are directly comparable across employees, and a certain amount of fairness can be achieved by this measure. This typically occurs with employees at the lower level of an organization, and if you have several employees doing similar or repetitive work that produces comparable metrics. This is decreasingly the case, however, as even – or especially — entry-level positions require more quality-minded, customer-oriented, problem-solving type thinking to achieve high-pressure work goals. So even when there are directly comparable metrics, there are many intangibles that come into play.

So inevitably, it seems that current management design requires that managers get in a room and essentially argue who is the best employee, whether they deserve a raise, and, in many cases, argue that the other employees are less deserving.

Now, what’s tough is that these decisions are way out of the employee’s control – even if they have done amazing work through the year.

Here’s why:

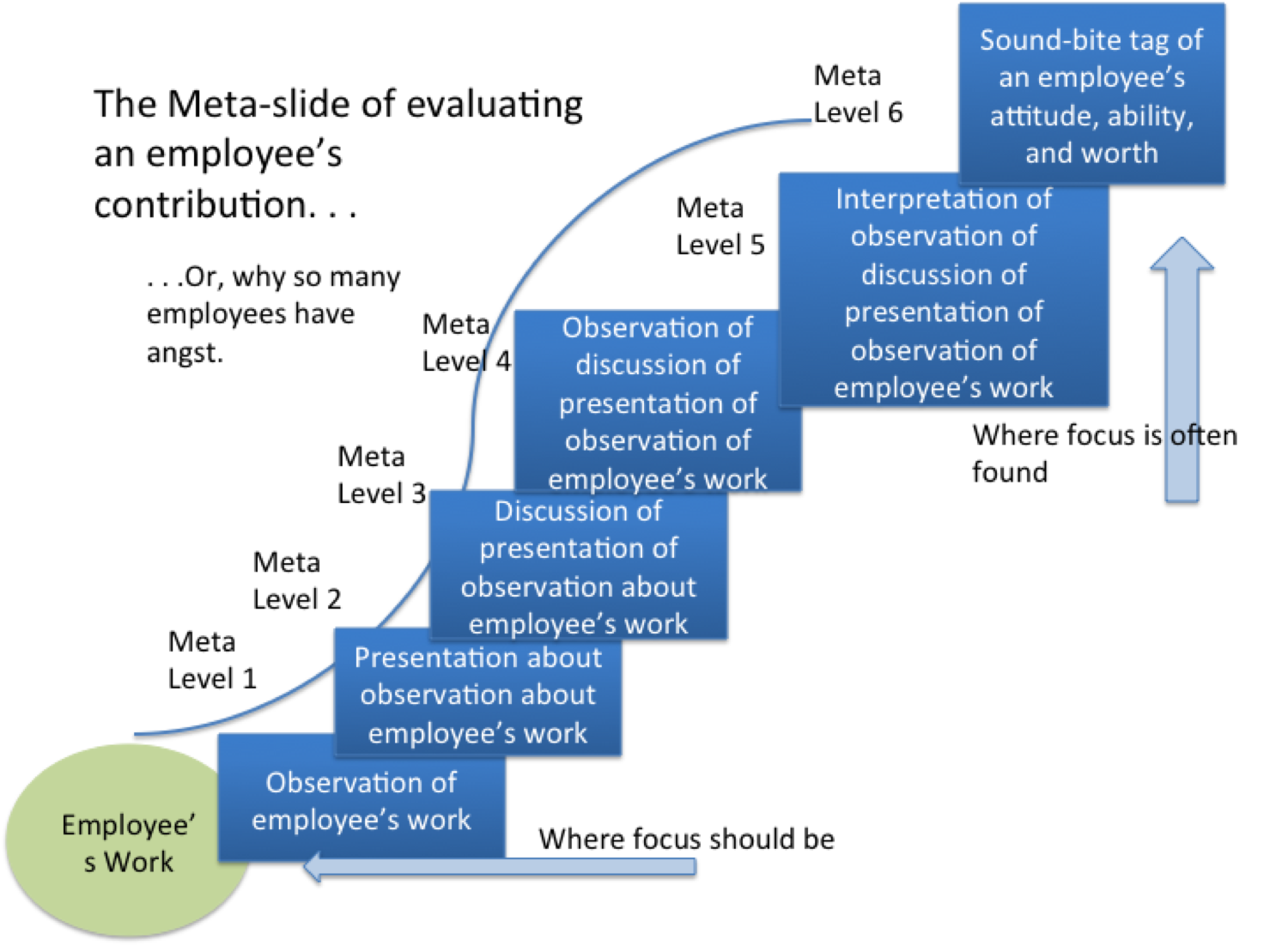

The discussion is inevitably a summary statement of everything an employee has done through the year, and that summary statement cannot possibly be true. In the “stack rank” discussion, a certain amount of meta-analysis of the employee’s performance and worth is required. Here’s what I mean:

Nine simple tips to make meetings more compelling

In my previous posts, I described a common mistake that managers make in regards to meetings: Calling mandatory meetings. In subsequent posts, I’ve listed criteria what makes a meeting more compelling from the participants’ view, and how you can even measure and track your meeting quality based on this criteria. In this post, provide nine baseline tips for making meetings more compelling, and helping you move your meetings up the meeting quality index.

1) Wait until there is a reason to call a meeting.

Instead of scheduling a regular meeting, and then try to find a use for it as that meeting approaches, wait until there is a reason for the meeting, and then call the meeting. For large groups, sometimes it is difficult to find a meeting time at the last minute, so the way to work around this is to have a regular meeting scheduled (such as a quarterly meeting). But if you don’t have immediate and obvious ideas for what will fill that time with, then cancel the meeting. Even if you have paid a deposit on the room, you’ll still save money if you don’t have immediate ideas for what the meeting is for.

More reasons mandatory meetings are bad for you and bad for your team

In my previous post, I discussed why mandatory meetings create a bad dynamic for your group or your team. The post centered on the cycle that the people who don’t want to attend – the ones that compelled you to make it mandatory – end up sabotaging your meeting anyway, making it a bad experience for you, the ones who wanted to attend, and the ones who didn’t want to attend.

But there are more reasons you should consider not making any meetings mandatory. And here they are:

Reason number 1: You can’t get everyone to attend anyway

This is an obvious point, but one that seems to be lost on many managers who require attendance at meetings. For any given meeting, there is going to be a group of people who will not or cannot attend. Read more

Making it a mandatory meeting sabotages the meeting

A common management practice is to make a meeting mandatory. I’ve seen regular team meetings that are called “mandatory”, “all hands” meetings that are called mandatory, special presentations with the group leadership that are mandatory. Lots of mandatory stuff going around! The problem is that if you feel compelled to call a meeting mandatory, it probably isn’t a very good meeting. In fact, if the tag “mandatory” has been added, then it is a sign that it’s going to be a low quality meeting.

When calling a meeting, the goal ought to be that you don’t feel compelled to call it mandatory. If you do feel compelled to get attendance by invoking the mandatory card, you should consider not having the meeting at all. Lack of employee interest a leading indicator that the meeting is going to be a bad meeting for all parties. Read more

A change agent brought in from the outside needs more than being a change agent from the outside

In my previous post, I explored the management “design” of hiring someone from a successful organization to bring change to your org. It’s a great idea – hire from the best, and you get the best. And presumably, this person is a top performer. Win-win! However, this can be a perilous design, as the organization you’re hiring from perhaps created great performance through the org processes and culture. The success was not necessarily via the individual’s greatness, but from the collective efforts of the previous org. But that’s what you’re hiring for when you hire this kind of expertise – change and improvement. So you need to be committed to it.

Let’s imagine that you hire a change agent who is ready to bring in the successful ideas and practices of the prior org to the new org. What more needs to be done to help this change agent be successful? Let’s take a look. Read more

Bonus! Five more reasons why discussing weaknesses with employees is absurd and damaging

In my previous post, I described five reasons discussing weaknesses with an employee often seems so awkward, despite the best intentions. Yet, managers are frequently asked to do so on an employee’s annual review form, which, by design, creates some unnecessary and damaging conversations. Here are five more reasons discussing weaknesses with employees fails: Read more

Five reasons why focusing on weaknesses with employees is absurd and damaging

Many managers are asked to discuss with their employees the various strengths and weaknesses of the employee. This often backfires, as the employee is appropriately suspicious of the manager’s intent when discussing “weaknesses”. The reason: This will appear on the employee’s annual performance review, and becomes part of the employee’s “brand” going forward – even if the weaknesses are irrelevant or nonsensical. As a result, any discussion about an employee’s weaknesses should be for the purpose of identifying and planning strategic needs of the organization. Instead what happens more often than not is that a discussion of an employee’s weaknesses is performed simply to document bad things about an employee. But why would you want to do that? You don’t. And here’s why not: Read more

The myth of “one good thing, one bad thing” on a performance review

A mistaken notion that many managers have is the belief that on a performance review they need to comment on and provide examples of both the good things and the bad things that an employee did over the course of the review period. This is sometimes taken to the next level, where the manager says one good thing and one bad thing about each area of the employee’s performance.

Here’s an example of something a high performer might see on a review:

Jeff exceeded sales expectations by 15%, placing him in the top 10% of the sales force. Jeff was below expectations in submitting his weekly status reports on time, and the reports he did submit were wordy.

This is a mistake and this practice should be stopped.